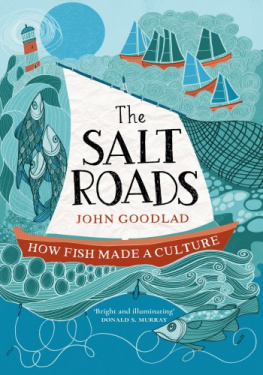

First published in 2022 by

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright John Goodlad 2022

The right of John Goodlad to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 1 78885 537 2

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

Typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Contents

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to everyone in Shetland, Faroe, Scotland, England, Iceland, the Basque country and elsewhere in Europe who generously gave me their time and shared their enthusiasm. They have inspired me to write this book. I am indebted to all those who have allowed me to use their photographs and to John Cumming for his masterful sketches. Andrew Simmons and the team at Birlinn could not have been more helpful and supportive. And, to my severest critics and greatest supporters my wife Wilma, and daughters Hannah Mary and Johanna youve taught me such a lot.

Prologue Pitch Dark

It was dark. Not just difficult-to-see-in-the-dark, but impossible-to-see-in-the-dark the kind of complete blackness that can only be found inside a room with no windows. But this was no darkened room; this was midnight in the middle of the North Atlantic in a hurricane. It was utterly chaotic: everything was moving around, violently and randomly. The old wooden smack, the Telegraph , first fell over to one side and then quickly rolled to the other, before plunging headfirst into a black void that seemed capable of swallowing her. The deck was awash with seawater as one wave after another crashed on board with a weight that made the boat shudder. And, as if there was not enough water on deck, torrential rain was being driven horizontally by the extreme southwesterly wind.

It would have been bad enough, thought James Smith, who was the skipper, if there had even been the slightest visibility. Some idea of where the next towering wave was coming from would have provided a brief warning of sorts. As it was, the Telegraph was being bombarded by breaking seas in total darkness. She was no longer moving through the sea, her sails having been ripped to shreds by the hurricane five hours ago, just as darkness had come down. At around the same time, what little light that came from the navigation lamps had been extinguished when they were torn from their mountings by a wall of water sweeping the deck. Total unseeing darkness is unusual at sea; there is usually some moonlight. But tonight, there was no moon, and it occurred to James that it really was as dark as pitch tar. He hated the darkness, and he longed to see a glimpse of moonlight, although he knew that would not happen until the storm passed.

James also knew that darkness was not his problem tonight. His crew were at the mercy of a weather event worse than anything he had ever seen before. The ability of the smack to cope had been seriously compromised when her sails had been torn. If a small area of sail was capturing the wind, the Telegraph was able to move ahead and was capable of being steered. The wind in the sail also heeled her over, which provided some stability against the random seas. But with shredded sails, the smack lost her momentum and could no longer be controlled. The two tall masts, now devoid of sail, acted as top-heavy weights, making the boat roll even more erratically. One minute the port rail was several feet under the water, the next the starboard rail was submerged as she wallowed helplessly in the storm.

The crew on deck were exhausted, cold and soaked through with seawater and driving rain. Apart from a few ships biscuits, no one had eaten anything for more than a day. They all knew how serious things were, although no one wanted to be the first to say so. Even if they had, time had long past when their shouting voices could have been heard above the roar of the wind and the thunder of the waves pounding the deck.

In his time as a fisherman, James had often contrasted being at sea in heavy weather with the gentle greenness of the family croft back home. A greater contrast could not be imagined, but he liked both. When at home he yearned to be back at sea, but tonight, as towering seas rose out of the pitch-black night sky, and as the wind screamed all around, James wished as never before that he was back at Pund, the small croft where he grew up. It is a magical place, nestling right by the shore on the west side of a narrow ridge of land known as Whiteness. All the crofts at Whiteness are on the east side of the ridge except for Pund, which sits by itself facing west. A narrow, almost enclosed finger of sea called Strom Voe runs north from the croft. Unlike most of Shetlands exposed coastline, the sea in this voe never gets rough. This was the secluded, sheltered and idyllic place where the Smith family were raised.

All the Pund children had to do their share of work on the croft, tending to the animals and looking after the limited crops that were grown. But Jamess real interest was in boats and the sea. Below the croft house is a stone beach, perfect for hauling small boats up and down. Every spare minute that he had was spent with his four brothers in the family boat, in the shelter of Strom Voe, before gradually venturing into more open waters when he was older. As soon as he left school, he became a fisherman, as did his four brothers. Like many men from Whiteness, they found berths on board the growing fleet of cod smacks. His oldest brother, John Smith, became skipper of the Anaconda at a young age. As the next oldest, James wanted to emulate his brothers success. He was ambitious. The four brothers, close in age, were regularly competing, but for James there was something more that drove him. Always wanting to be the best, he was strong-willed, sharp-witted and a good seaman. He was confident that he could be as good a smack skipper as his brother better, in fact.

This ambition and determination, while central to his character, did not always define him. He could be easy-going and he had a sense of humour. Before he spoke, the relaxed twinkle in his light blue eyes would often preface a funny remark sometimes at his own expense. Whenever he needed to concentrate on a task at hand, however, his demeanour would suddenly change, as his eyes became intensely focused. Always precise in his approach, whether it was catching a sheep on the croft or setting a course on his smack, everyone knew they could rely on him. His blue eyes and high cheek bones were typical of all the Smiths from Pund, as was his dark hair. James had that heady mix of Scandinavian and Scottish genes that characterises so many Shetland families.

After several years sailing as a fisherman on board different smacks, he managed to get a job as mate for a couple of years. In 1877, when he was 27 years old, he got the break he was looking for: one of the islands most successful cod merchants, Joseph Leask, offered him the job of skippering the Telegraph . She was one of the companys largest smacks, carrying a crew of 14. James had been keen to prove himself and he went on to land a bumper catch of cod that year, making her one of the best-fished boats in the fleet. Joseph Leask was happy his cod smack was making money, confirming that his choice of the young skipper had been a good one.

Next page