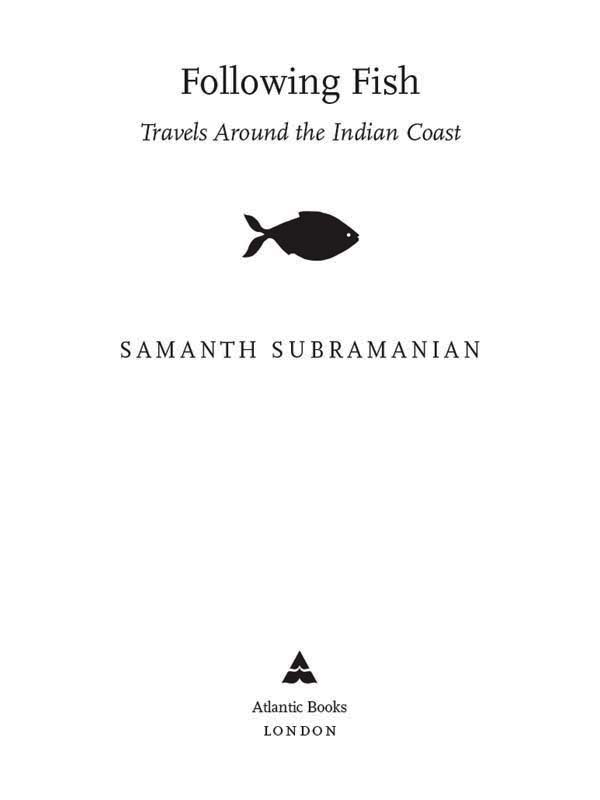

Following Fish

First published in India in 2010 by Penguin Books India, a division of the Penguin Group.

Published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britain in 2012 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Samanth Subramanian 2010

The moral right of Samanth Subramanian to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 0 85789 600 1

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 0 85789 601 8

E-book ISBN: 978 0 85789 602 5

Printed in Great Britain [printer details].

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To my parents,

who taught me to write and to read,

for which I can never thank them enough.

Rise, brothers, rise! The wakening skies

pray to the morning light.

The wind lies asleep in the arms of the dawn

like a child that has cried all night.

Come, let us gather our nets from the shore

and set our catamarans free,

To capture the leaping wealth of the tide,

for we are the kings of the sea!

No longer delay, let us hasten away

in the track of the sea gulls call,

The sea is our mother, the cloud is our brother,

the waves are our comrades all.

What though we toss at the fall of the sun

where the hand of the sea-god drives?

He who holds the storm by the hair,

will hide in his breast our lives.

Sweet is the shade of the cocoanut glade,

and the scent of the mango grove,

And sweet are the sands at the full o the moon

with the sound of the voices we love;

But sweeter, O brothers, the kiss of the spray

and the dance of the wild foams glee;

Row, brothers, row to the edge of the verge,

where the low sky mates with the sea.

The Coromandel Fishers, Sarojini Naidu

Introduction

When I was twelve years old, and we were living in Indonesia, my sister and I once accompanied my parents to one of the regular dinner parties that anchored the calendar of the Indian expatriate. As per routine, we were shunted off upstairs with our friends, to watch television and play video games. Our parents sat downstairs with the other parents, probably to complain about how all their children did these days was watch television and play video games.

Summoned for dinner an hour or so later, we came down into the dining room, to a large table laden with various plates of food. My memory seems to have captured this scene and then, like a rogue design editor, Photoshopped it into even sharper significance. The peripheral details of the other dishes are blurred, but the centrepiece of the table remains in vivid focus. It was a whole, steamed fish, coloured such a wretched gray that it reminded me instantly of death. I also recall a smell that lurked over the table like an invisible warning. I did not eat much dinner that night.

Taste is the most temperamental of our senses, remarkably resilient in some ways but also malleable enough for one to be repulsed for life by a single experience. That dinner party was sufficient to put me off fish for the next decade, and even in my early twenties, when I cautiously began venturing back towards seafood, I stuck wherever possible to the safe, taste-slaying possibilities of batter and the deep fryer. Fish and chips I could face, but not fish in soup, or fish baked or grilled or, worst of all, steamed. This was not as restricting as it sounds. Everybody else in my family is rigidly vegetarian, and I was happy enough with poultry and meat when I ate out.

Depending on how you look at it, this makes me either the least ideal or the most ideal person to write about fish. Naturally, I prefer to take the latter view, and to believe that being unencumbered by dense schools of fish-related memories is a distinct advantage. But this book goes beyond considering fish merely as food. Particularly in a nation with as lengthy and diverse a coastline as Indias, fish can sit at the heart of many worlds of culture, of history, of sport, of commerce, of society. It can knit the coast together in one dramatic swoop: the hilsa, the pride and joy of Bengal, now often arrives in many fish markets from Gujarat, at the very opposite end of the coastline. Or it can fragment the coast into a multitude of passions and traditions, each different from the one found a hundred kilometres to the north or south of it. Looking more closely at even one aspect of these worlds is like picking up the most visible thread of a fishing net, and suddenly seeing the entire skein lift into view.

Much as I would have liked to begin in Kolkata and ramble right around the edges of the Indian peninsula over several continuous months, I wasnt able to travel that way. Instead, I tore large chunks of time out of my working life, which is possibly why the journey divided itself easily into individual segments, and thence into individual chapters. I flew a lot. I also took buses and motorcycles and trains and cars, dozens of auto-rickshaws (including one that I drove, rather poorly, on a deserted Kerala highway), many flimsy-looking boats, twice a bicycle, and once a jerry-rigged motor vehicle for which no technical term exists.

Almost always, I travelled alone, and so I came to depend on the kindnesses of people who knew people who knew my friends. They would ease my entry into alien worlds, at least initially; when I didnt follow the language, they would translate and add helpful annotations. In their comforting shadow, emboldened by the fact that they belonged even if I didnt, I could loiter endlessly, watching and listening, starting up dialogues where I chose. In this way, I aspired to become what V. S. Naipaul once called a discoverer of people, a finder-out of stories.

In pottering about the Indian coast and writing about it, I have not intended to produce a guide to lead others down the same route. This is, in that sense, not a how-to-travel book but a travelogue a record of my journeys, my experiences and observations, my conversations with the people I met, and my investigations into subjects that I happened to find incredibly fascinating. Put another way, it is simply what I believe all travel writing to be in its absolute essence: plain, old-fashioned journalism, disabuser of notions, destroyer of preconceptions, discoverer of the relative and shifting nature of truth.

New Delhi

January 2010

On hunting the hilsa and mastering its bones

T HE DAY BEFORE I ARRIVED IN K OLKATA , THE BAZAAR began to burn. Fire ate through fourteen levels of the Nandaram Market complex and its adjoining shops, and late in the evening, I fancied that the smoke still slept in the air. It wasnt just because of traffic smog that I struggled to decipher a green-on-white sign mounted on a building, or to spot the little toenail clipping of a moon; I genuinely sensed the acridity of fresh smoke. Later, a friends father informed me that what I was smelling was the burning of leaves, a winter-evening pastime in Kolkata, as popular as dog walking or badminton. (That green-on-white sign, by the way, turned out to announce the premises of the Pollution Control Board.)

Next page