W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

New York London

Originally published under the title Negotiauctions: New Dealmaking Strategies for a Competitive Marketplace

Subramanian, Guhan.

[Negotiauctions]

Dealmaking: the new strategy of negotiauctions/Subramanian, Guhan

p. cm.

Originally published under the title Negotiauctions: New Dealmaking Strategies for a Competitive Marketplace.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Negotiation in business. 2. Auctions. I. Title.

HD58.6.S83 2010

658.4'052dc22

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

INTRODUCTION

On Wednesday, January 21, 2004, at approximately 8:30 a.m., representatives from seven bidding groups convened at the offices of a well-known investment bank in midtown Manhattan for the auction of Cable & Wireless America (CWA), the bankrupt American division of British-based Cable & Wireless PLC. After a brief introduction, the bidders were sequestered into separate conference rooms, and for the next twenty-one hours, CWAs bankers and lawyers went from room to room negotiating privately with each of them. A month earlier, the stalking-horse bid process had implicitly valued CWA at $125 million. But by 6:00 a.m. on January 22, the best bid was in only the mid$60 million range.

CWAs bankers and lawyers assembled in a conference room overlooking Park Avenue. With more than a century of dealmaking experience among them, they asked themselves a simple question: What do we do now?

This book tries to answer the question What do we do now? for both buyers and sellers in situations like the sale of Cable & Wireless America. It will come as no surprise that the CWA bankers and lawyers did not run to their bookshelf for guidance. The reason is that existing negotiation theory is inadequate in these complex dealmaking situations. In many fields, the gap between what practitioners want and what academics can provide simply reflects the limits of the existing knowledge base. It would be nice, for example, if financial economists could provide practitioners with a single, definitive, and completely precise way to value assets. But existing finance theory cannot do this.

In negotiations, the gap between what sophisticated dealmaking practitioners want and what academics can offer is not for lack of knowledge. Rather, it is the failure of negotiations as a field to incorporate elements of auction theory that are highly relevant to how deals are actually made. Aside from fixed-price processes (such as buying lettuce at the grocery store), auctions and negotiations are the only two ways in which assets are transferred in any market economy. It is therefore surprising that the academic thinking on these two mechanisms has developed in separate silos.

The broad-brush history goes like this: Auction theory has its roots in game theory and microeconomics. It generally assumes that the structure of the situation is well specified and that all parties are rational, and then develops optimal strategies for sellers and buyers. Negotiation theory starts with basic microeconomics, but it has developed in a direction that includes experimental economics, social psychology, behavioral economics, and the legal profession, among other fields. Despite the same underlying subject matter (the transfer of assets), the two fields have grown further apart over time, as auction scholars have become more technical and negotiation scholars have become more applied. This trajectory is the opposite of what their inherent interconnectedness would seem to require.

Rather than trying to solve problems from inside these two academic silos, I try in this book to guide practitioners in solving problems as they present themselves in the world. Specifically, this book brings together the two parallel streams of research in auctions and negotiations to provide guidance to practitioners who are involved in what I call negotiauction situations. Professor Jeffrey Teich of New Mexico State University trademarked the term in 2001, in conjunction with his Independently, I introduced the term in a 2004 article with Professor Richard Zeckhauser from Harvard University, to capture the murky middle ground that falls between pure one-on-one negotiations and pure Sothebys-style auctions. In my definition, a negotiauction is the commonplace situation in which negotiators are fighting on two frontsacross the table for sure, but also on the same side of the table, with known, unknown, or possible competitors.

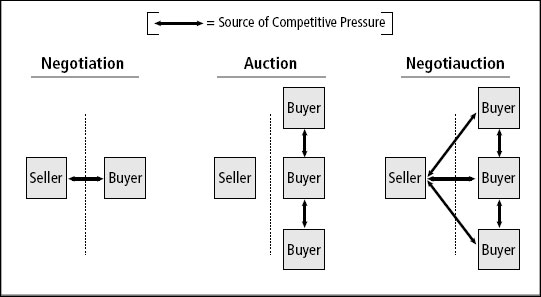

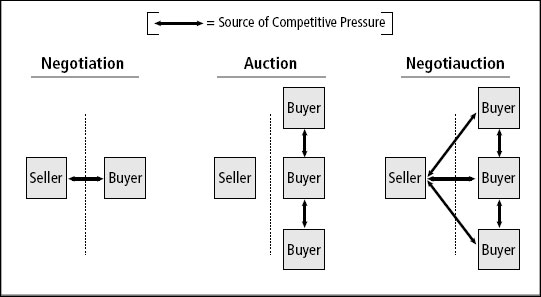

Visually, a negotiauction can be represented as in Figure 1. The competitive pressure in a negotiation comes mainly from the across-the-table dynamics. In contrast, in an auction the competitive pressure comes primarily from same-side-of-the-table dynamics. Once the seller has established the process in an auction, he becomes a passive participant. Competition among the bidders does most of the work in pushing up the price.

Figure 1. Negotiations, Auctions, and Negotiauctions Compared

The key point in the diagram is that most real-world situations include aspects of both same-side-of-the-table competition and across-the-table competitionwhat I call a negotiauction. I have spent the last decade studying negotiauctions, through Harvard Business School case studies, consulting work, expert witness testimony, and empirical studies. In this research I initially thought about negotiauctions as a subset of all negotiations, a special kind of negotiation that had auction elements. But in my executive education teaching and in conversations with businesspeople, I discovered that the term resonates with what they experience every day in an increasingly competitive marketplace. As a result, I stopped asking, What kinds of negotiations are negotiauctions? and began asking, What kinds of negotiations arent negotiauctions? There are answers to this question, of course, but they are fewer than I imagined.

There is of course the proverbial risk that when you have a hammer, everything becomes a nail. The litmus test for me came when I began teaching about negotiauctions to executive education groups at the business school, the law school, and the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard. Across these diverse audiences, the negotiauction concept resonated strongly with what these practitioners experienced every day in their negotiating lives. From salespeople trying to get in the door, to government officials putting public procurement contracts out to bid, to general counsels trying to secure outside legal services, negotiauctions were everywhere.

I came to realize that the negotiauction concept resonates with dealmakers because it captures the way most high-stakes assets are actually transferred. Furthermore, in my research I have found that (1) even experienced dealmakers make costly mistakes in negotiauction situations; (2) recognizing these mistakes, dealmakers crave guidance on how to play in a more sophisticated way; and (3) general principles can be derived from systematic observation of negotiauction successes and failures.