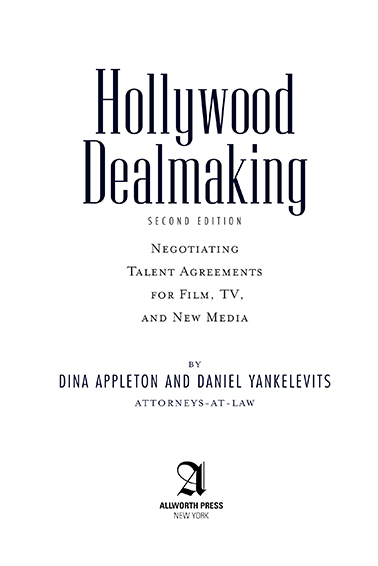

2010 Dina Appleton and Daniel Yankelevits

All rights reserved. Copyright under Berne Copyright Convention, Universal Copyright Convention, and Pan-American Copyright Convention. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher.

14 13 12 11 10 5 4 3 2 1

Published by Allworth Press

An imprint of Allworth Communications, Inc.

10 East 23rd Street, New York, NY 10010

Cover design and interior design by Leah Lococo and Jennifer Moore

Page composition/typography by SR Desktop Services, Ridge, NY

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Appleton, Dina.

Hollywood dealmaking : negotiating talent agreements for film, TV, and new

media / by Dina Appleton and Daniel Yankelevits.[2nd ed.]

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-58115-671-3 (alk. paper)

eBook ISBN 978-1-58115-736-9

1. Artists contractsUnited States. 2. Television producers and directorsLegal status, laws, etc.United States. 3. Motion picture industryLaw and legislationUnited States. 4. TelevisionLaw and legislationUnited States.

I. Yankelevits, Daniel. II. Title.

KF390.A7A67 2009

343.73'0783848dc22 2009038654

Printed in the United States of America

For my son and daughter, Adam and Ali. Remember to

always follow your dreams. And a special thank you to my parents,

Yigal and Diana, who have sacrificed without hesitation so that

I didnt have to, and who continue to encourage and inspire me;

and to my wife, Lori, who is the rock of our family.

Dan

To my son, Jake (my pride and joy).

Dina

* * *

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful for the assistance of the many individuals who offered their guidance in the preparation of this book, as well as to those who contributed their useful quotes. A special thanks to our agent, Andree Abecassis, for her tireless efforts on our behalf, and to Ron Reitshtein for his diligence. We are also indebted to our publisher, Tad Crawford, and his editorial team at Allworth Press.

* * *

DISCLAIMER

The information in this book is intended to help the reader better understand the dealmaking process in Hollywood. The material presented is neither exhaustive, nor is it presented on behalf of the authors respective employers; all views and opinions are their own. It is not offered as legal advice, nor should it be construed as such. The authors strongly recommend that the reader consult with an experienced entertainment attorney to address each individual situation and any legal documentation.

INTRODUCTION

to the

DEALMAKING PROCESS

R elationships play a key role in the dealmaking process in Hollywood. Not only does a good relationship ensure that a phone call will be returned or that a script will be read, but it helps cut through difficult negotiations when a deal is ready to be made. Once a level of trust is established between the negotiating parties, each side may more readily accept the others bottom line.

THE PLAYERS

The major players in Hollywood routinely take part in power breakfasts, lunches, and dinners, cultivating their relationships with others in the business. Such principal players include the talent representatives (i.e., talent agents, personal managers, and entertainment attorneys), the buyers (studio executives and independent producers), and, at least indirectly, the guilds.

Talent Agents

A talent agents primary role is to procure employment for her talent clients (i.e., the actors, writers, directors, producers or below-the-line crew who she may represent) and to negotiate such clients employment agreements, possibly in conjunction with an entertainment attorney.

In California, talent agencies are regulated by the California Labor Code, section 1700 (also known as the California Talent Agency Act), and are required to be licensed by the State. This legislation requires that talent agencies post a surety bond in the amount of $50,000 prior to the issuance of their agency license. The regulations also require agencies to submit agents fingerprints and references, to maintain a trust account and accurate records, and to submit the agencys form of talent representation agreement for approval by the Labor Commissioner.

Talent agents primarily make their living by commissioning the fees earned by their clients. Customarily, an agent will receive 10 percent of the clients gross earnings. For example, if an actor earned $60,000 for her acting services on a film, the agent would be entitled to a $6,000 fee. State legislation (mentioned above) and most guild regulations (discussed below) prohibit agents from taking a higher fee. In some cases, agencies will take a packaging fee in lieu of its standard 10 percent commission fee. This occurs in cases where the agency has packaged (or put together) a number of key elements in a film or television project (such as the writer, the director, a lead actor, etc.) and sold the project as a package to a buyer. In recent years, agencies have creatively sought out alternative revenue streams. William Morris Endeavor Entertainment, for example, provides marketing services to television networks and other clients.

Agencies representing guild members must be franchised by the relevant talent unions or guilds and must abide by the guilds agency regulations. Most established agencies are members of the Association of Talent Agents (ATA), a nonprofit trade union comprised of companies engaged in the talent agency business. The ATA is the entity that negotiates the agency regulation agreements with the various talent unions and guilds (including Screen Actors Guild [SAG], the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists [AFTRA], Actors Equity Association [AEA], the Writers Guild of America [WGA] and the Directors Guild of America [DGA]). It should be noted that the SAG/ATA agreement expired on October 19, 2000 due to the inability of the parties to agree on fundamental issues. The two sides continue to work together, despite the absence of a formal agreement. The various guild regulations not only restrict the terms of the agency representation agreements, but also give talent the right to terminate the agency agreement in the event that the agent is unable to secure any offers of employment during a set period. These guild agency regulations, along with the California Talent Agency Act, are the foundation upon which talent agencies operate.

Being represented by an agent provides legitimacy to a talent, and the more prestigious the agency, the better. It should be noted that many production companies will not accept literary materials unless they are submitted through an established agency or entertainment attorney with whom they have a business relationship. The theory is that if the project is represented by an agent, it must be of a certain standard, and hence, worth the investment of time needed to evaluate the material.

There are hundreds of talent agencies in Los Angeles and elsewhere (most notably, New York City), some representing several different types of talent and some that focus their representation on a particular niche (such as television writers or commercial actors). Moreover, some clients have more than one agent for different areas of representation. For example, an actor client may be represented by one agency for film and television and another for commercial work. In recent years, agencies have branched out and/or expanded, forming alternative divisions that encompass such areas as sports, branded entertainment, and new media. Mergers and acquisitions, such as the recent Endeavor/William Morris Agency merger, have consolidated power in the entertainment industry and representatives are seeing that their clients are looking to them to provide more services and create more opportunities, and agencies are responding by changing their business models to meet that demand.

Next page