Acknowledgments

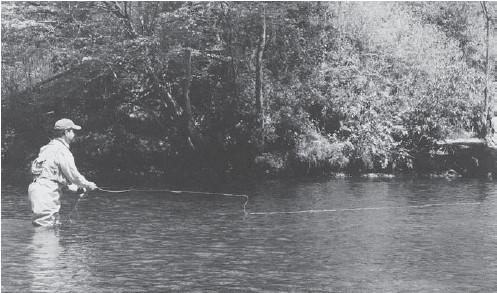

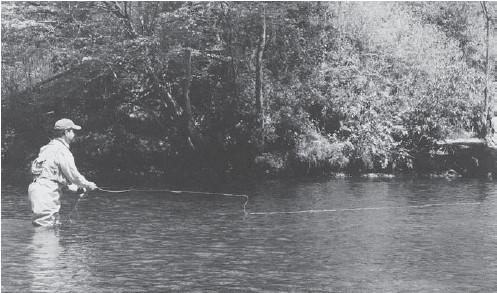

Our daughter Ellie gave up Saturdays and Sundays in the springtime to stand in rivers and take pictures of her crazy dad waving a long stick and trying not to fall in. It was good to spend time outdoors with her again.

Dr. Bill Chiles helped on both sides of the camera, as model and photographer, and introduced me to some wonderful southern waters.

In his letters, Lefty Kreh shared wisdom on knots and the testing thereof.

Umpqua Feather Merchants, Orvis, Scientific Anglers, and Frog Hair collectively provided more than a mile of tippet material, most of which I broke testing and comparing knots.

As always, my greatest thanks go to my wife, Mary Jo, for her patience and encouragement. She makes projects like this one possible.

Shorter versions or parts of the following chapters were articles for American Angler magazine:

A Comfortable Load, in the MayJune 2003 issue.

Basic Leadership Skills, in the NovemberDecember 2002 issue.

Saltwater-Style Rigging for Freshwater Fish, in the MayJune 2001 issue.

The Fine Points of Angling, in the JulyAugust 2003 issue.

Positive Buoyancy, in the JulyAugust 2002 issue.

Lessons from the Salt, in the NovemberDecember 2001 issue.

Appropriate Force, in the SeptemberOctober 2003 issue.

Discover more Fishing books, eBooks, and expert advice from the best in the field

With expert instruction and detailed, step-by-step photos, Stackpoles Fishing titles help advance your skills to the next level.

Visit Stackpole Books Fishing webpage

Cast 90 FeetWhether

or Not You Want To

The colorful fly-rod ad in the glossy magazine was a fair specimen of its type. It showed an angler firing an astonishing length of line over the water, his casting arm extended until his shoulder tendons creaked and his six-inch-tall loop zooming toward the distant horizon of the beautiful setting. The headline said something about never settling for second-best performance. Beneath the photo, a dozen lines of copy made reference to the rods ultra-high-modulus fibers, revolutionary resin system, and groundbreaking taper design. No fish is out of reach for an angler using one of these rods, the ad implied.

We shouldnt be too hard on companies that commission ad agencies to create such messages. This is America, and Americans want the latest, coolest, fastest, highest-performance stuff, even if we dont always need it or know how to use it. Take a look around. Folks who drive barely well enough to negotiate parking lots buy 300-horsepower cars that look great creeping along at 12 miles an hour in urban traffic jams. Citizens purchase computers more powerful than anything NASA had for the Apollo program so that they can send ungrammatical e-mail and dirty jokes to friends who dont have time to read the stuff anyway. Consumers bring home stereos that can reproduce frequencies inaudible to the human ear and generate enough volume to make concrete buildings crumble, and then listen to talk radio or collections of music with such titles as Greatest Dentist-Office Hits of the Seventies .

A high-modulus, high-performance, extra-fast-action fly rod is a marvelous casting tool. But is it the right tool for this kind of fishing? Softer, slower-action rods make more sense for many anglers.

Theres no harm in any of those things, of coursea certain amount of overcapacity, perhaps, but no real harm. Fly fishers, however, can do themselves some harm when they blithely accept the notions that the possession of an allegedly high-performance fly rod somehow translates into high-performance angling and that the latest, hottest long-distance rod is always the best one to use. In fly fishing, overcapacity can hurt you.

Not that I have anything against the newest, lightest, highest-modulus fly rods. In many circumstances, they are wonderful casting implements, light and crisp and a joy to use. Most of them are also tougher and less likely to break than their forerunners were.

But too many anglers dont understand that when its applied to a fly rod, the term high-performance doesnt refer to what the rod does . A fly rod doesnt do anything. If its truly a high-performance model, a rod lets or perhaps helps a very good fly caster do certain things in certain situations. The rods qualities might or might not matter to you or me; sometimes they might even hinder us from fishing well.

Before considering why a high-performance, high-modulus rod might not be the best one to have, perhaps we should spend a minute looking at what happens when we cast and thinking about the differences between this years most-hyped line launcher and a fly rod made, say, twenty-five years ago. This line of inquiry is more complicated and involved than many anglers suspect.

BEND AND STRETCH AND TRY NOT TO COLLAPSE

Obviously, a fly rod bends when you make a cast with it. How easily and deeply it bends and how vigorously it straightens (recovers is the usual term) determine its casting properties. So far, its all pretty simple. But the event of bending is not so simple as it seems. A typical graphite fly rod is a tapered tube. This tube consists not of a solid substance (as, say, a copper pipe does), but of several materials. The carbonized fibers that make the rod springy run lengthwise. A plastic resin holds the carbonized fibers together. You can think of a graphite rod blank as a hollow, tapered bundle of long, extremely thin wires held together by epoxy glue. Thats a crude picture, but it suits our purpose.

When a rod bends, the fibers on the outside of the curve are stretched. They dont like stretching, and they want to return to their original length. Thats why the rod straightens when the load is removed. The modulus that anglers and rod companies make such a big deal of is a truncation of modulus of elasticity, a measurement or mathematical description of how a material behaves when stretched. A high-modulus fiber resists stretching more and returns to its original length more forcefully than a low-modulus fiber does. Graphite is a higher-modulus material than fiberglass, and thats the main reason that a graphite rod is stiffer than a glass one.

Every time you cast, then, you stretch part of your fly rod. As the rod bends, another thing happens: The tubes cross section wants to go out of round. Thats true of any tube, as you can demonstrate by bending a plastic drinking straw. Bend the straw more than a little bit, and it suddenly kinks and collapses at one point. Anyone who has tried to bend electrical conduit without a proper tool has experienced this same problem.

If a fly rods cross section goes out of round under stress, the tube kinks and collapses, and the rod breaks. A tubular fishing rod must maintain its round cross section under considerable strain. Rod builders use the term hoop strength to refer to this requirement. With fiberglass, hoop strength wasnt an issue. Most glass rods were (and many still are) made with woven cloth in which equal numbers of fibers lie at right angles to one another; half the fibers run lengthwise, and the other half run across the blank. The crosswise fibers form hoops and, not surprisingly, provide hoop strength. Thats why most fiberglass rods are so tough; they have loads of built-in resistance to deforming and kinking because half of the fibers contribute to structural integrity.

For the most part, the carbonized fibers that give a graphite fly rod its power and spring run along only the lengthwise axis. Since these lengthwise fibers do not form hoops, they contribute nothing to hoop strength. If made with materials available in the 1970s, when graphite fishing rods first came on the market, a fly rod consisting only of carbon fibers and plastic resin would collapse and break instantly when bent.