DEDICATION

Ian and Julie wish to dedicate this book to their father, Robert Whitelaw, with fond memories of the many happy hours we spent together on the riverbank when I was a boy, and with thanks for all the support and encouragement that you have given me over the years.

Published in 2015 by Stewart, Tabori & Chang

An imprint of ABRAMS

Text copyright 2015 Quid Publishing

Design: Lindsey Johns

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014942977

ISBN: 978-1-61769-146-1

Stewart, Tabori & Chang books are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

115 West 18th Street

New York, NY 10011

www.abramsbooks.com

CONTENTS

Introduction

Fishing has often been referred to as an art as much as a sport, and in the case of fly-fishing the artistry extends beyond the practice to the creation of the flies themselves. Carefully designed and tied, often delicate and intricate, the flies are a large part of what makes fly-fishing so enjoyable, so what better way to examine the history of the sport than through a chronological sequence of fifty flies?

NO WEIGHT, NO BAIT

You might ask Which fifty flies?, but lets start with a more basic question. What is a fly? The term artifical fly was already being used in the 16th century to include caterpillars and worms, and over the intervening years it has been applied to larvae, nymphs, leeches, baitfish, frogs and, in the case of carp flies, even berries and seeds, so it clearly doesnt just mean a representation of a flying insect. Our definition is something that is too light to be cast any distance without a fly line, has no food-like scent or taste and is designed to fool a fish into eating it only by its appearance and behavior.

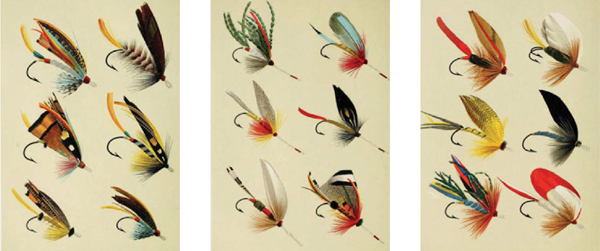

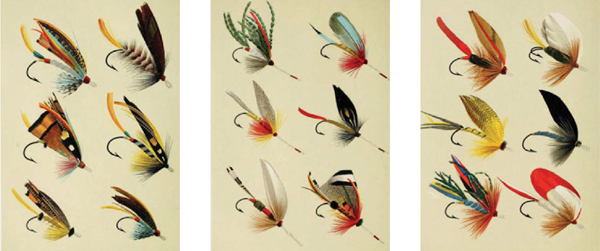

Three of the many plates from Mary Orvis Marburys Favorite Flies and Their Histories show the color and variety in North American wet flies toward the end of the 19th century. The dry fly was about to change the picture radically.

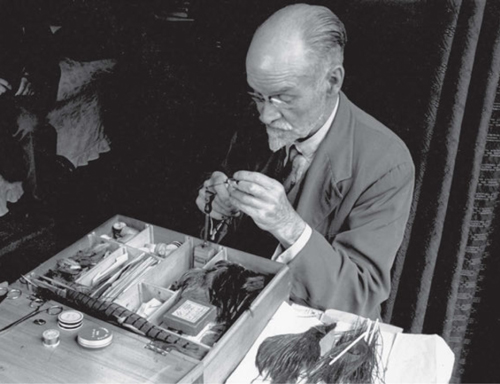

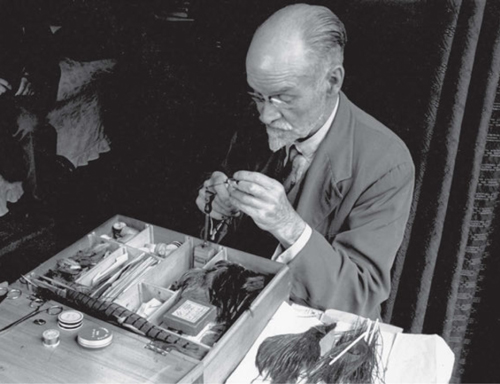

A flytiers desk in the mid 1940s reveals traditional materials such as pheasant tail feathers, rooster capes and silk tying thread. Within a few decades these would be joined by a host of synthetic materials, opening new avenues for the tier.

HOOKS TO HANG THE HISTORY ON

That narrows it down to just a few thousand patterns, so how have the fifty been chosen? There is no one answer, because they have been chosen for a variety of reasons. Some are milestones in the history of fly tying, some are here as representatives of broad classes of fly, some act as a focal point around which to discuss broader issues within the sport, some are examples of the possibilities opened up by the discovery or invention of particular fly-tying materials, and some allow us to explore the larger-than-life characters who created them. Some are just too effective to leave out. Each of them has a story that extends far beyond itself to include the flies that led up to it and those that it inspired or that embody similar principles or materials. Together they chart the evolution of fly-fishing, the increasing diversity and sophistication of flies, the widening range of fish species that are being caught on the fly, and the geographic spread of the sport.

Above all they chart our deepening understanding of the natural worldof the fish themselves, their behavior and perception, the items on which they feed, their habitats and the ecosystems of which they are a part. This, after all, is the knowledge on which the art and science of fly-fishing are founded and we need as much knowledge as possible, for, as John Steinbeck once wrote, It has always been my private conviction that any man who pits his intelligence against a fish and loses has it coming.

It is not every man who should go a-fishing, but there are many who would find this their true rest and recreation of body and mind. And havinglearned by experience how pleasant it is to go a-fishing, you will findthat you are drawn to it whenever you are weary, impatient, or sad.

W.C. Prime,Go A-Fishing

Its buoyancy and versatility have made deer hair a staple in the dry flytiers toolkit since the 19th century. As well as forming many different kinds of wing, it can be spun and sculpted to create shaped bodies and heads.

FIFTY AND THE REST

For each fly we list the year in which it was first tied, by whom and where, and include a watercolor illustration that depicts the fly in its original form. Schematic diagrams show what materials areor wereused to make each part of the fly. Each of the fifty flies is really a starting point, and as the story of each one unfolds, connections with other flies and other flytiers are made, and trends in the practice of fly-fishing appear. The materials used change from basic, locally available fur and feathers to the most exotic and colorful plumage from around the world, then to dyed replacements for endangered feathers and finally to a host of synthetic materials and new breeds of fly.

Changes in the technology of fishing both affect and are affected by the evolution of fly design, and interspersed throughout the book there are State of the Art sections that summarize the development of rods, reels, lines and hooks in each of the last three centuries.

Finally, there is a bibliography of fly-fishing books and a list of useful websites, as well as a mention of some of the many anglers, flytiers and historians who have so generously helped to put this book together.

Eyed hooks started to become popular in the later part of the 19th century, but eyeless hooks whipped to gut remained in use well into the 20th.

WHEN DOES THE HISTORY START?

No discussion of the origins of fly-fishing can fail to mention the first known description of the use of an artificial fly. Claudius Aelianus (or Aelian), the Roman author of On the Nature of Animals, writing in about 200 CE, tells us that in Macedonia (now northern Greece) there is a small fly called Hippouros that looks a bit like a wasp, hums like a bee and is eaten by fish when it lands on the water. Fishermen dont use the fly as bait because if a mans hand touch them, they lose their natural color, their wings wither, and they become unfit food for the fish. Instead, the local anglers wraped a hook with crimson red wool and attached two wax colored feathers from a cockerels throat (presumably as wings). Using six feet of line on a six-foot rod, they cast this out and the fish went for it and got hooked. It isnt clear why the artificial fly is red while the natural looks like a wasp, but this is undoubtedly fly-fishing. It has come a long way since then.

Next page