Acknowledgments

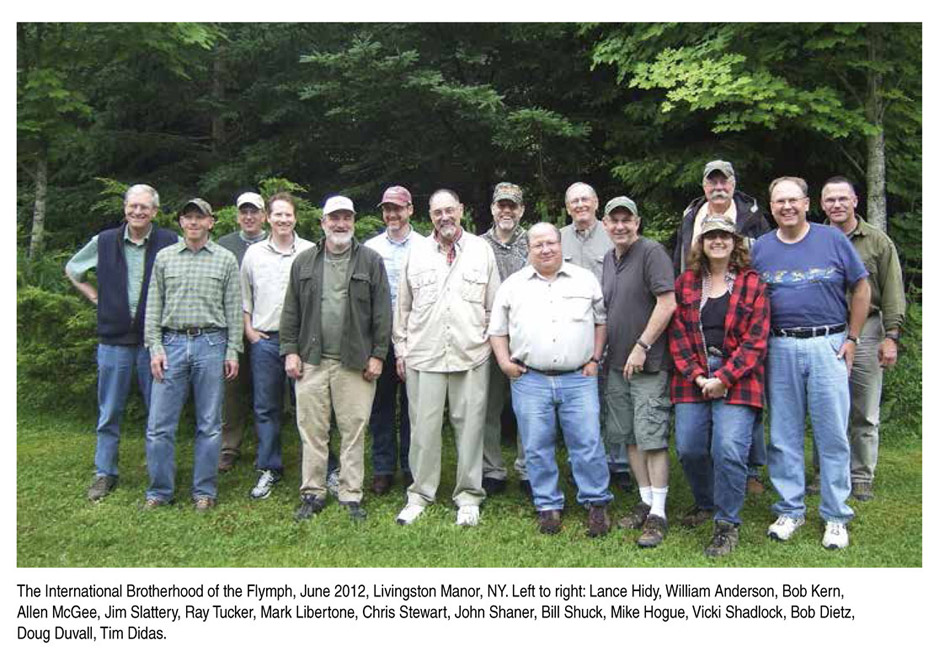

I want to thank a few fellow anglers and fly tiers I feel are at the forefront of wet-fly experimentation. Steven Bird lives on the American reach of the Upper Columbia River in northeastern Washington. His blog Soft-Hackle Journal is an amazing look at someone who lives trout fishing, and knows what hes talking about when it comes to soft-hackles. He is always experimenting with new materials for flies, but at the same time feels that the Pflueger Medalist is the best reel ever made, and still fishes the two he bought back in the 1960s as a teenager. As he puts it, Both are imbued with the mojo of a thousand rivers. His flies also reflect his wisdom. Lance Hidy is the son of Pete Hidy and continues his fathers work with flymphs and wet flies. Lance is a direct connection to some of the most innovative development of wet flies ever. Michael Brucato lives in Massachusetts. He has guided in the area for over a decade and continues to introduce many to the power of fishing soft-hackles. Sandy Pittendrigh, of Montana Riverboats (http://montana-riverboats.com), fishes out of Bozeman, Montana, were he builds drift boats. Many of the naturals he has photographed are shown here to illustrate Western trout-stream insect species. Jon Rapp lives and fly-fishes in central Missouri and is actively involved in Trout Unlimited. He often visits his local trout streams just to collect, photograph, and identify the biomass, to better understand his home waters. I appreciate all of these friends who contribute to the genre, and I think you will find their work to be valuable as well. Most of all, I sincerely thank my wife, Hyun Soon, who captured many of the photos in this book, and my son, Harrison, both of whom have accompanied me on many a long fishing trip.

L eaving the great waters of Roscoe, New York, on my way to visit my brother in Catskill Park, I didnt know what to expect as far as the trout streams were concerned. Id fished the Beaverkill, the Willowemoc, and the East Branch Delaware River tailwater many times but had never found time to venture farther up into the Catskills until now.

Margaretteville was a sleepy little town that I might never have explored, but for this trip. I soon found myself walking down Frog Lane to the bridge crossing the upper East Branch of the Delaware River. There I found a fast-water run that I felt sure would hold some trout. I cast across-stream and mended the line to slow the drift. The bead thorax Hares Ear Soft-Hackle sank, and my mind zoned in on the drift. I tried to keep the fly in the drift lane as long as I could, to give any fish that might be there as much opportunity to strike as possible. Amazingly, on the first cast the line paused just as it was beginning to swing into the current of the fast channel, and I lifted the rod tip slightly. The hook bit, and I was into a fish. Then, whatever it was got serious, and I got excited. The heavy fish dove to the streambed. The water was fast and deep in the middle channel, and as it got deeper, I couldnt follow downstream much. The fish started to run. I was trapped. The fish was now below me, and the weight and the water velocity strained my 5X tippet.

I decided to try to let the fish tire itself out by using side pressure on the rod, holding it horizontally to the water, and choking up on the rod blank. It worked well enough that the fish wasnt running anymore. I was then able to negotiate the fish across the deep middle channel, over to my side. I regretted not having a net. I played it as gently as I could, hoping the hook would hold. After nearly 15 minutes of eternity and multiple close tail grabs, I finessed the trout close enough to put my hand underneath to support it. It was a beautiful 16-inch brown that appeared to be wild. I removed the fly and supported the fish facing upstream in the slower current long enough to feel that it had regained its energy, then let it swim away. As I walked back up the gravel road to my brothers house in near darkness, I felt a sense of accomplishment and pride in knowing that my flies and techniques had worked well on a stream that Id never fished before.

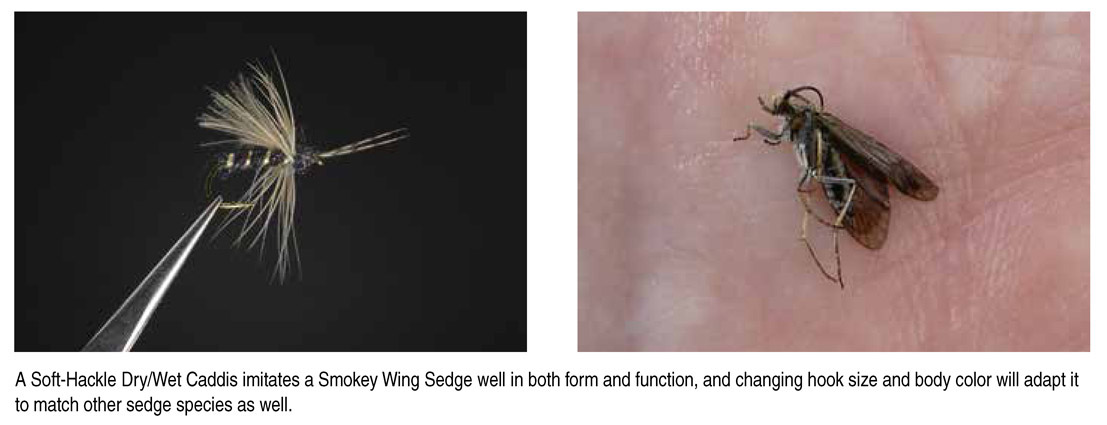

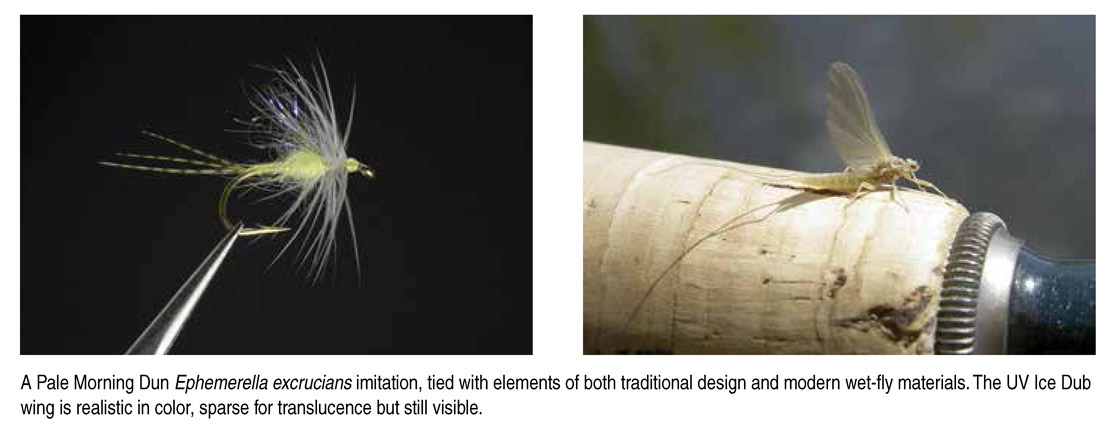

Over the last few years, Ive been excited about the resurgence of soft-hackles in fly boxes, fly bins, catalogs, blogs, message boards, and, most importantly, on and in the water. I feel that many anglers are realizing the true potential of this style of flies. They represent not only the physical shape, but also the movement of the natural stream insect. Soft furs make the bodies of these flies breathe and move like gills on the natural. Soft-hackles from a wide range of feathers pulse in the currents. Modern synthetic materials give the fly the flash and translucence of the nymphs natural exoskeleton. By fishing them with the correct behavior of the natural in mind, we complete the process of imitation.

My first book, Tying and Fishing Soft-Hackle Nymphs (Amato, 2007), explains wet-fly philosophy, tying methods, traditional and modern soft-hackle nymphs, and the tackle and methods used in fishing them. This new book expands on the field, and I hope it pushes the boundaries of how we think about soft-hackle flies and what they can imitate. Soft-hackles imitate not only the life stage, shape, and color of the natural insect, but its life as well, through the combination of soft-hackle collars, translucent fur, or synthetic body materials that move and breathe in the water currents, and sometimes abdomens that move in imitation of the swimming nymph. This imitation of life triggers an instinctive response from trout.

While many may think of soft-hackles as small, lightweight flies fished only on or near the surface, you can fish them from the bottom to the top of the water column. A skilled angler can present his flies to the level of the fish, which is of utmost importancefish dont want to move far for a fly, and often wont in fertile streams, choosing instead to eat food that comes to them. Soft-hackles can be fished in technical match-the-hatch situations, with specific methods designed to imitate the behavior and movement of a specific species.

Traditionally, wet flies fall into three general classifications: spiders or wingless wet flies, winged wet flies, and flymphs. Spiders are perhaps the most well known as they are commonly envisioned when someones mentions a soft-hackle. The sparseness of their design imitates mayflies well. Winged wets are traditionally tied with opaque wing feathers often from turkey slips. Howevery, by using feather tips or modern transluscent fly materials we can now imitate the wings of sub-surface mayflies more realistically. Flymphs are the buggiest wet flies of all; the bodies often are made of fur or fur/sparkle synthetic dubbings that bring more movement and life to the fly in addition to soft-hackle collar. They can be tied with or without tails as desired and intended for matching species as such.