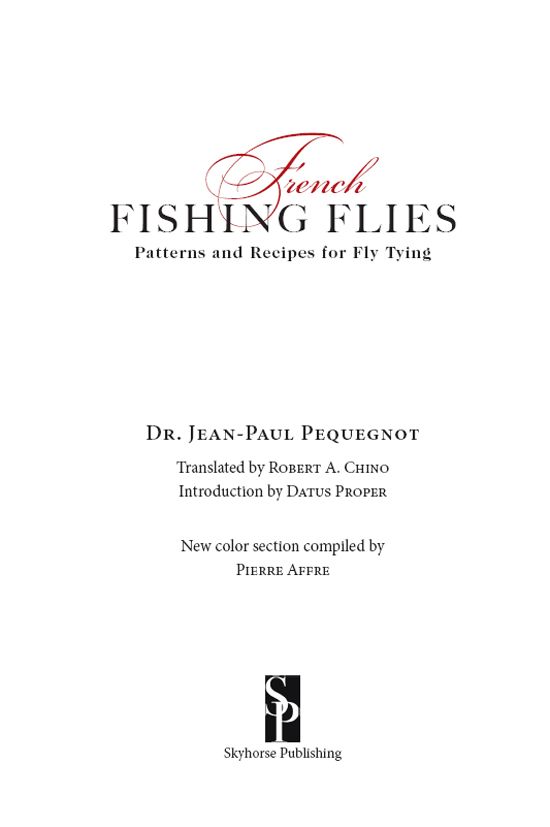

Books by Dr. Jean-Paul Pequegnot

Rpertoire des Mouches Artificielles Franaises

1975, 1984, Besanon

lArt de la Pche la Mouche Sche

Flammarion, Paris 1969, 1977, 1981

lArte della Pesca con la Mosca Secca

Sperling & Kupfer, Milano, 1985

Pche la Mouche en Bretagne (With P. Phlipot)

1971, Besanon

La Loue

1981, Besanon

La sant de votre enfant

Flammarion, Paris, 1983

Copyright 1984, 1987, 2012 by Jean-Paul Pequegnot

Translation copyright 1984, 1987, 2012 by Robert A. Chino

Interior photographs copyright 2012 by Pierre Afre

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifs, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifcations. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on fle.

ISBN: 978-1-61608-544-5

Printed in China

Introduction

It is about time someone published a good book in English on the French fly-fishing tradition. We know that France is rich in most resourcesnatural, human, artistic, and gustatorybut how many of us have fished there? The country is not, for anglers, what the travel agents call a destination resort. I recall one useful reference in an American book (by Leonard Wright) and none in any American magazine.

This book is mostly about flies. You might like to know something about the streams and fish too, and I cant help much. What I know comes from a few hours of fishing in France, a few days in Switzerland, and a few years in Portugal. That at least gets me through the culture shock, which, for an American of the catch-and-release generation, is considerable.

My American and British friends generally dropped out. I stayed with the fishing mainly, I guess, because a trout stream in Europe plays the same music as a trout stream in the Appalachians, and because it hurts to stay in town when the buds are breaking and the rains are washing angleworms across the sidewalks. It is also painful to watch a stream being cleaned out, whether with bait or flies or spin-bubbles. But my European friends treat me well. They also treat trout wellonce they are in the creeland I can appreciate the idea that the highest destiny of a fish is to be poached in white wine. Its sort of like the Congressional Medal of Honor, which is a splendid thing to have if youre dead anyhow.

Latin Europe convinced me that the brown trout is as good a product as nature ever got around to evolving. Those I caught were mostly small, mind you, but their freedom lent a feeling of wilderness to hills that had been populated since the last Ice Age. Each stream had its own strain, different in appearance and habits from trout in the next watershed, but having in common centuries of experience in avoiding nets and setlines and maggots and, more recently, insects that look like everyday food but have a sting to them.

You can take it that the French professionals did not persist in fly fishing for reasons aesthetic. Their income came from their catch, and, judging from this book, they found it profitable to fish small flies on or near the surface. So did I. When I could see the flyeven at a distance on fast waterI had a chance of controlling its behavior, and perhaps of hooking the only legal-sized trout of the day. It did seem important to imitate the behavior and size of the natural insects. I did not see much selectivity to color or even to shapebut then I never got on the French chalkstreams or the fertile rivers that Dr. Pequegnot fishes.

Most of the streams I tried would look comfortable to you if you knew the upper Willowemoc in New York, Big Run in Virginia, the Pecos in New Mexico, or another small freestone water with wild trout. And your American flies would work in southern Europe. By the same token, you might reckon that your fly box is getting inbred, and this book will provide healthy stock for an outcross. The flies wont look foreign to the trout in your home stream.

Francelike Americahas been influenced by the English fishing tradition. Dr. Pequegnot makes this clear. But in the French case, English ideas were imposed on native habits. That was not the case in English-speaking America: for us, the culture of angling began in England, was lifted intact to the New World, and then changed in response to local conditions. The change was remarkably slow; Americans still use artificial flies called Iron Blue Duns and Blue-Winged Olives, even though we lack the natural British flies on which the artificial ones were originally based.

We also retain the old concepts of patterns, in which fliesor at least serious, imitative fliesare classified by color (look again at Iron Blue and Blue-Winged Olive). If an artificial fly does not resemble the natural in color, then most of us do not consider it imitative. We may catch a trout on a fly that resembles the natural in behavior, size, and shape, but if the color is different, we conclude (by a remarkable leap of logic) that the trout was not selective.

In what category, then, shall we place a fly that happens to be rose champagne in color? La Loue is not intended to imitate a specific insect. But it is small, it is soberly dressed (for the color-blind), and it has the shape traditionally associated with representations of mayfly duns. Furthermore, it takes difficult fishand I gather that they include trout, though it started as a grayling fly. The Halfordian solution would be to discard this creation as philosophically inconvenient. Dr. Pequegnot does not take that way out. He tries La Loue, finds it neither more nor less effective at catching fish than other hackle flies, but recommends it because of its remarkable visibility to the angler. This kind of analysis may seem brutally frank (if you have made an investment in expensive hackles of many hues), but it is not culture-bound.

For most of us, the important thing about this book is not that it is French but that it is one of the few works of any nationality on the design of trout flies. The author did not simply collect French fly patterns. If he had, he would have produced an interesting curiosity, but he would not have sent Americans to their fly-tying vises. The best patterns evolve around local insects, and when transplanted to another environment, the patterns are often abandoned or modifiedas happened with the Blue-Winged Olive, of which nothing is left (in America) except the name. Good design, on the other hand, is universal. That is as true of trout flies as of aircraft, furniture, and your wifes blue jeans. And design is why this book has as much to do with the Henrys Fork as with the Risle.

By design, I mean that Dr. Pequegnot explains each flys structure and how it affects behavior on the water. (I never understood how the peculiar architecture of the Mole Fly was supposed to work until I read his description of the Pont-Audemer, a derivative dressing.)

He appraises other fly-tiers contributions as fairly as his own. (This gives us a wide range of alternatives from which to choose.)

Next page