CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

M ARMALADE, porridge, grouse, whisky and haggis are just a few Scottish food classics that have travelled the globe. They owe their fame, largely, to the millions of expatriate Scots who have taken these eating and drinking habits with them. What Scot in deepest Africa could survive Burns Night without haggis and a bottle of whisky?

But Scottish classics have made it on their own reputation too. Seafood from cool, unpolluted waters is undisputed for quality. There are sweetly succulent soft fruits that mature best in the long, mild Scottish summers. Excellent beef and lamb come from rich grasslands. And there is the unique distillation of whisky, the water of life.

Whisky and smoked salmon have been the trailblazers, successfully exported to every corner of the globe. Now other seafoods oysters, mussels, langoustines, crabs and lobsters are catching up. Marmalade has made it up Mount Everest and grouse is flown to top restaurants in London, Paris and New York.

In the meantime, at home, a growing band of enlightened Scottish chefs have taken up the prime quality, locally-produced tag on their menus. They promote Scottish foods in season, support local producers and provide visitors with a unique eating experience.

Though Scotland is a small country its landscape varies dramatically. Fertile agricultural lands in the East and wild mountains in the North, together with seas and islands, shape the nature of the produce and the cooking of the people.

In early times, pastoral Celts herded animals and followed the grazing seasons making milk, butter and cheese throughout the spring and summer. The seafaring Norse salted and smoked fish, to save them for winter supplies. Both traditions survive in a variety of local cheeses and many fish delicacies from smokies to finnans.

The eating traditions have also been shaped by sources of heat and cooking equipment. Slow-burning peat, rather than coal, created cooking heat for much of the population in early times, which resulted in a tradition of slow simmering and stewing in a large pot over a gentle peat fire. Scotch Broth, haggis and Clootie Dumpling are just a few of the classics that depend on the long slow simmer.

On the baking front, few Scots had ovens and baked mostly on a flat metal plate a girdle with a handle that was hooked over the peat fire. It was on this that oatcakes were first made, followed by lighter bannocks, soda scones, pancakes and crumpets. Not every home today has a girdle, but every commercial baker still has a hot plate. (English supermarkets in Scotland have had to equip their in-house bakeries with hot plates for the popular girdle-baked scones, pancakes and crumpets.)

Though oatmeal only began to take over from barley as the staple grain around the end of the 17th century, it is now the Scottish grain. More versatile than barley, which is now mostly used for distilling whisky, the advantage of oatmeal is that it can be ground into so many different cuts: pinhead for haggis, coarse for mealie puddings, medium for oatcakes and fine for bannocks.

Oatmeal, in porridge and brose taken with milk, became the backbone of the Scottish diet for most of the 18th and 19th centuries and is reputed to have given Scots of previous generations their sturdy health. In the 1980s, an American professor discovered from his researches that one of the reasons for this was a gummy soluble fibre in oats, which helped to prevent heart disease in his patients. The news popularised oat-eating throughout the world. But you need look no further than classic Scottish cooking for the most original and frequent use, today, of healthy oatmeal.

Catherine Brown

CHAPTER ONE: BROTHS

BROTH CLASSICS

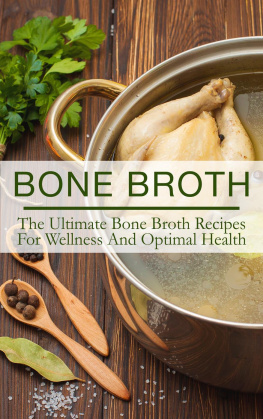

Scotch Broth

This is the comfortable pot-au-feu of Scotland the pot luck of homely and hearty old-world hospitality, says Meg Dods in The Cook and Housewifes Manual (1826).

For kitchen routines of her day, the attraction of Scotch Broth is its convenience. Made with a large piece of beef or mutton, preferably salted for a week, it provides soup and meat for several days. It is also versatile, in that it changes with the seasons roots in winter, greens in summer but always with barley and dried peas. The old style pot barley, without the bran removed, is preferred to polished pearly-white, which cooks too quickly and releases too much thick starch into the broth.

Scots can thank their early historical connection with France, during the period of Auld Alliance, for the comfortable pot-au-feu broths, as well as the frugal habit of cooking in a pot rather than roasting on a spit. Scotch Broth, however, also becomes popular in England around the late-eighteenth century, though according to Meg Dods it is not always served up in an approved Scottish style.

English books of cookery, order a sauce for meat boiled in Scotch Broth, of red wine, mushroom-catsup, and gravy with cut pickles a piece of absurd extravagance, completely at variance with the character and properties of the better part of the dish namely with the bland, balsamic barley-broth of Scotland.

An early Scottish recipe in Elizabeth Clelands A New and Easy Method of Cookery (Edinburgh, 1759) includes: a chopped leg of beef, a fowl, carrots, barley, celery, sweet herbs, onions, parsley and a few marigolds. The eighteenth-century traveller, Faujas de Saint-Fond, while on a trip round Mull is served with:

a large dish of Scots soup, composed of broth of beef, mutton and sometimes fowl, mixed with a little oatmeal, onions, parsley and a considerable quantity of peas. Instead of bread, as in France, small slices of mutton and giblets of fowl are thrown into this soup.

But it is the influential, and outspoken critic of the Scots, the English lexicographer, Dr Samuel Johnson, who first spreads the word about the merits of Scotch Broth. In August 22, 1773 when Johnson is dining with his travelling friend, James Boswell, at the New Inn on Castle Street, Aberdeen dinner begins with a tureen of Scotch Broth with barley and peas in it. Johnson eats several platefuls. He seems very fond of the dish, remarks Boswell in his journal.

You never ate it before? asks Boswell.

No, sir; but I dont care how soon I eat it again.

When writing later to an English friend, Johnson remarks:

Barley broth is a constant dish and is made well in every house.

Cock-a-Leekie

Cocky-leeky: so thick that the ladle stauns o itsel, is how James Hogg the Ettrick Shepherd describes the version that he enjoys with his cronies, Christopher North and Timothy Tickler, in their favourite Edinburgh tavern. The racy column about their ambrosial nights (Noctes Ambrosiana) which appears in Blackwoods Magazine from 1822 to 1835 also refers to hotch potch, which, along with cocky-leeky, they think the two best soups ever created.

Ageing cockerels and mature hens are just the thing to give this broth body and flavour. And as tasty hens and cockerels range freely in everyones backyard, so sturdy leeks king of the soup onions grow in family vegetable gardens. Along the Lothian coastline to the east of Edinburgh market gardeners become so famous for their leeks that their variety of the Common Winter Leek is known as the Musselburgh leek. It is the perfect partner for an old bird.

Distinguished from other leeks by its long leaf, (or green flag) and short white, it is described by William Robinson in