CONTENTS

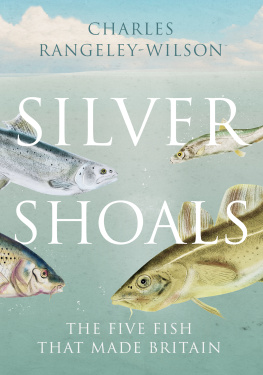

ABOUT THE BOOK

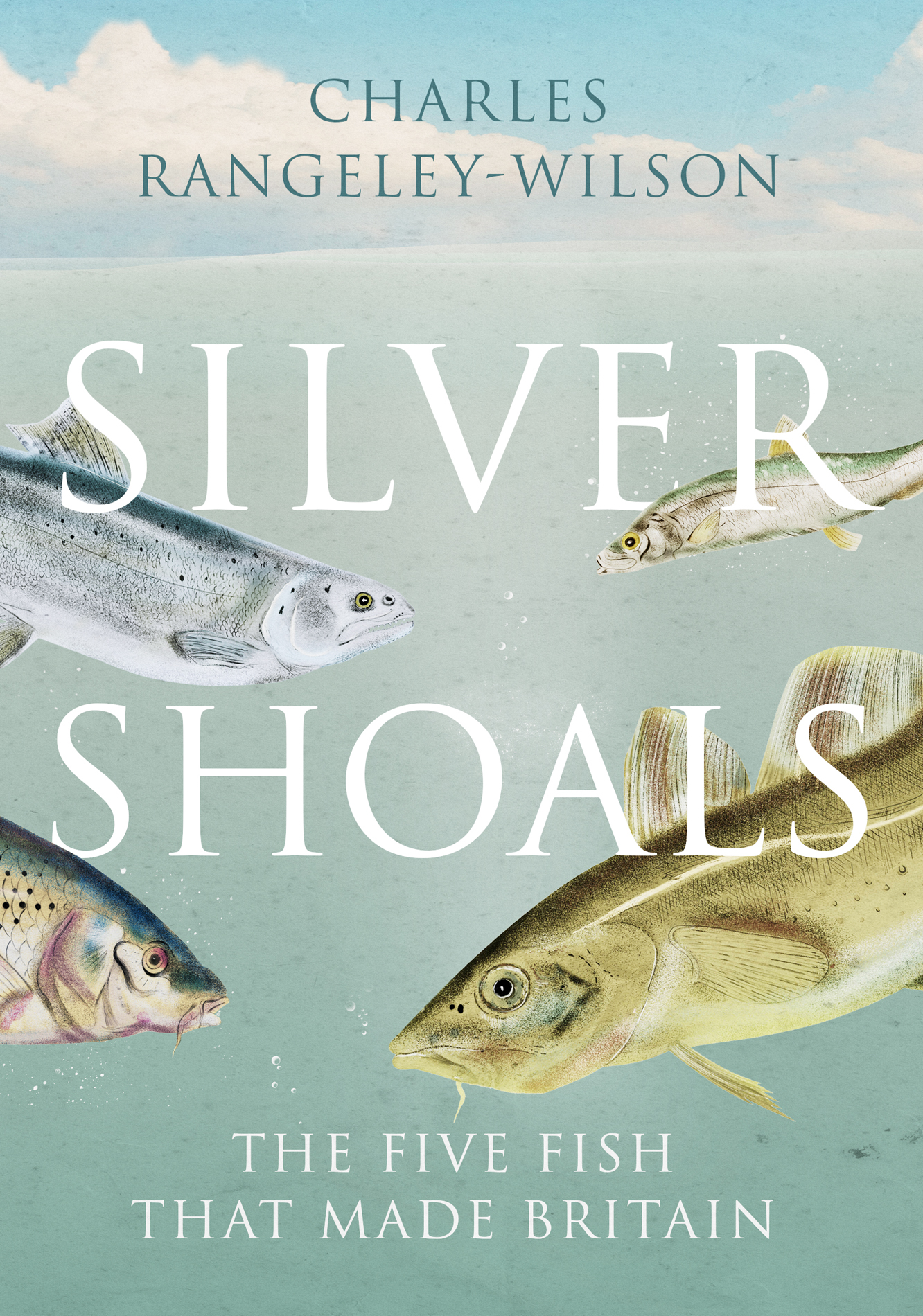

On these rain-swept islands in the North Atlantic man and fish go back a long way. Fish are woven through the fabric of the countrys history: we depend on them for food, for livelihood and for fun and now their fate depends on us in a relationship which has become more complex, passionate and precarious in the sophisticated 21st Century.

In Silver Shoals Charles Rangeley-Wilson travels north, south, east and west through the British Isles tracing the histories, living and past, of our most iconic fish cod, carp, eels, salmon and herring and of the fishermen who catch them and care for them.

In the company of trawlermen, longshoremen, conservationists and anglers Charles goes to sea in a trawler, whiles away hot afternoons setting eel nets, tries to bag his first elusive carp and drifts for herring on Guy Fawkes night as fireworks starburst the sky.

Underscoring this journey is a fascinating historical exploration of these creatures that have shaped our island story. We learn how abundant and valued these fish were centuries before our current crisis of over-fishing: we learn how eels built our monasteries, how cod sank the Spanish Armada, how fish and chips helped us through two World Wars.

Of course there is a deeper environmental dimension to the story, but Charles optimistic perspective is this: no one is more invested in fish than the fishermen whose lives depend on them. If we can find a way to harness that passion then the future of fish and fishermen in Britain could be as extraordinary as its past.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Charles Rangeley-Wilson is an award-winning writer. He is a passionate conservationist, founder of the Wild Trout Trust and the Norfolk Rivers Trust and advisor to WWF on English chalk streams. He is the author of two books of travel and fishing writing, Somewhere Else and The Accidental Angler, which was also televised by the BBC, and Silt Road: The Story of a Lost River. His other work for the BBC includes the critically acclaimed film Fish! A Japanese Obsession. He lives in Norfolk with his wife and two children.

ALSO BY CHARLES RANGELEY-WILSON

Somewhere Else

The Accidental Angler

Silt Road: The Story of a Lost River

To Orri Vigfsson fisherman and conservationist 10 July 1942 1 July 2017

This island is made mainly of coal and surrounded by fish.

Aneurin Bevan

The fishermen know that the sea is dangerous and the storm terrible, but they have never found these dangers sufficient reason for remaining ashore.

Vincent Van Gogh

PROLOGUE: HOME

FISHERS END

Ive looked out over the North Sea, on and off, for much of my life. I can see it now from where Im typing at the back of the house. The wind is blowing hard from the north this evening and already waves are breaking over the outer sandbanks. The sea is almost glowing, both beautiful and menacing. The sight of the pounding water and a flickering light over the waves that keeps on vanishing for moments at a time reminds me of a story I read about fishing boats out on the sandbanks in a big storm, how once the boats broke anchor and got up on the sand, they were finished. The sea, so it went, rushes in from an unhindered sweep of 600 miles and makes matchwood of any boat unlucky enough to drift on to the hard sand-flats. The story was told by Frank Castleton, one of the last fishermen from my local town, Kings Lynn, who could still remember as an old man in the 1980s its fishing community. Frank described what he saw the morning after that storm, the four smacks that had gone down and how all that was left of them were the sternposts, with a few bits of planking hanging to them and odd scraps of gear such as stoves lying forlornly around. Though he didnt intend it this way, Franks description was a metaphor, I thought, for what had happened to him and his community.

Carved wooden bench-ends from St Nicholas Chapel in what used to be the fishing quarter of the town Fishers End depict the glory days of the Kings Lynn fishery when Franks ancestors sailed each spring in square-rigged fishing boats to the seas around Iceland, and returned in the autumn loaded to the gunwales with cod which they had salted and dried on that distant shoreline. The bench-ends are 600 years old and for five and a half of those centuries Kings Lynn was a thriving fishing port: as were Lowestoft and Great Yarmouth, Grimsby, Scarborough, Bridlington, Berwick and dozens of other towns along the east coast of England and Scotland. Theres not much left of fishing in many of those places now: a brown-shrimp fishery in Lynn, a herring-processing plant in Great Yarmouth; just these odd scraps lying forlornly around.

In Kings Lynn only a few houses remain in Fishers End, along with street names and family names on gravestones scattered through the churchyard, or the phone directory. To walk around there now you would never guess that the place-name described a history. Apart from anything else, no one calls that part of the town Fishers End any more. The original Fishers Fleet where those early Renaissance fishing boats moored, granted in perpetuity to the Lynn fishermen by Elizabeth I, now lies under the tarmac behind Enterprise Rent-a-Car and the ABC Car Wash. An ivy-wrapped level crossing marks the spot where the channel once passed under what used to be Pilot Street, but is now called John Kennedy Road.

Most of the little fishermens cottages that surrounded the Fleet were done away with when Kings Lynns authorities cleared away the towns slums in the 1930s and the 1960s, when the sailors, sailmakers, fish merchants, mariners, harbour pilots, fishermen, fisherwomen, fishwives, ropemakers, boatbuilders, twine-spinners and cord-wainers who lived there were rehoused throughout the town. Only two small cottages are left, known by their old name of Trues Yard. Somehow they survived the demolition and in the 1980s a trust was founded to buy and preserve them as a memorial to the vanished community. Side by side they stand in the shadow of the fishermens chapel, one-up one-down, their bedrooms barely big enough for the bedsteads, and the kitchens dwarfed by a single dresser and chair. It was six kids to the bed the last time anyone lived in them, Mum on the floor behind a curtain and Dad downstairs on the rag rug in the winter the rug with a red diamond at its centre to ward off the Devil or on a fishing smack in summer. But Kings Lynns fishing industry was already on the way out by then.