Table of Contents

To

Susan Rabiner

with thanks for inspiration and encouragement

Male and female created he them....

Be fruitful and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.

Genesis 1:27-28

PREFACE

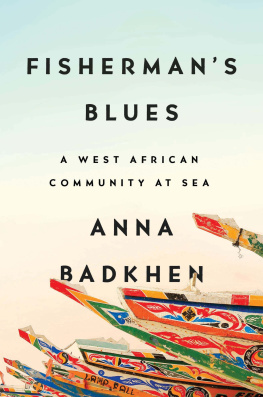

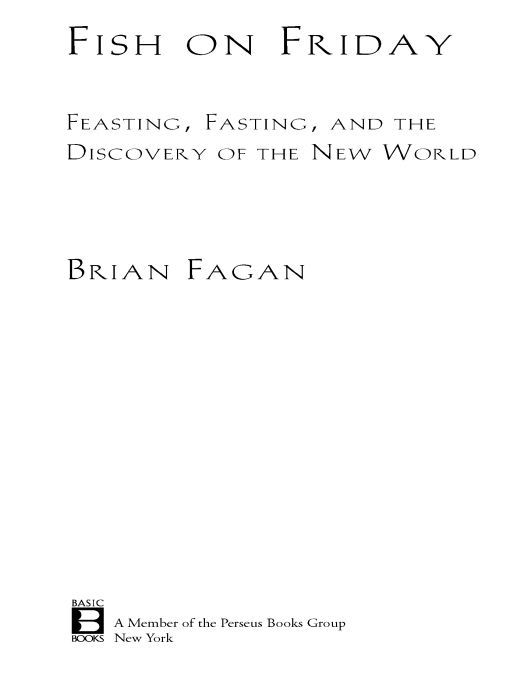

THE THOUSAND-YEAR JOURNEY

The fascination of a fishermans life is that he reaps his harvest from an unseen world through whose insecure and perilous crust he throws down his sacrificial gifts for a reward that may be small, or may be great, but is always uncertain. All that he knows of that obscure region beneath him is that it is inexhaustibly rich.

Leo Walmsley

A brave wind is blowing and the caravels are rolling, plunging and throwing spray as they cut down the last invisible barrier between the Old World and the New. Thus Samuel Eliot Morison conveys the drama of the momentous dayOctober 14, 1492when Christopher Columbus, Admiral of the Ocean Sea, made landfall in the Bahamas thinking he had reached the outlying islands of Asia.

The voyages of 1492 and 1497 made Christopher Columbus and John Cabot icons of the Age of Discovery, explorers whose transatlantic journeys transformed global geography. Everyone knew that Europe, Africa, and Asia were three contiguous continents, and most people believed the earth was spherical. Thus it was theoretically possible for them to sail directly from Europe to Asia by heading into the Atlantic, the empty and hazardous Western Ocean. Columbus and Cabot did just that, but instead of Asia they found a new continent teeming with unknown peoples and exotic animals. They had achieved geographic immortality.

Except for a small group of Vikings who created a short-lived settlement in Newfoundland during the late tenth century, Columbus and Cabot are generally assumed to be the first Europeans to reach the Americas. Both were expert mariners who came along at a time when academic knowledge of geography had been enriched by Marco Polos explorations in Central Asia and China. Paolo Toscanelli of Florence had estimated the distance to China and speculated about possible rest stops along the way. The convergence of broadening academic knowledge, new designs of oceangoing ships, lust for the wealth offered by the spice trade, and sailors prepared to undertake the risky journey produced an impetus for discovery that was not present a century earlier.

But the familiar names of history, Cabot and Columbus, did not bring Europeans to the New World. The hard-won knowledge of the Western Ocean was acquired over many generations by people who did not talk freely about their experiences or share knowledge with others, least of all with scholars or government officials. I argue in this book that the finding of North America was not a brief moment of iconic discovery but a thousand-year journey fueled by Christian doctrine and a search for hardtack.

This is not a tale of kings, popes, and statesmen, but of merchants, monks, and fishermen who lived and worked far from the spotlight of history. In all but a few cases we shall never know their names, but their devotion and labor yielded greater wealth than the gold of the Indies. They led Europeans to North America to fish and then settle there, well before the Pilgrims landed on a continent said to be inhabited only by Indians. Much of this journey is cloaked in historical obscurity, owing to lacunae in official records as well as the silence of many of the players. We can follow their doings only by triangulation from diffuse and often indirect clues.

Abstinence, atonement, fasting, and penance lay at the core of Christian belief; from the earliest times fish had a special association with such practices. The traditional fasting days were Fridays and Lent, when Christians atoned for the suffering of Christ on the cross. As Christianity spread across Europe and religious communities proliferated, so did the number of holy days. By the thirteenth century, fast days took up more than half the year.

Once eaten on special occasions, by the eighth and ninth centuries, fish was a preferred food for abstinence days throughout Christendom. Fishing had always been an important subsistence activity for people living by lakes, rivers, and seashores. To supplement these resources, monks and nobles turned to fish farming to provide the catch for holy days. Eels were so commonplace that they became a form of currency. But as populations rose and the grip of Christian doctrine tightened, even thousands of hectares of fishponds proved insufficient to satisfy the demand on meatless days. By the tenth and eleventh centuries, fish had become not a catch but a commodity. The stage was set for the extraordinary journey to North America.

Sometime around the tenth century, Baltic herring fishers and Norse fisherfolk learned to preserve herring by salting it in brine-filled barrels. The Sknia fishery in southern Sweden spawned an industry that carried herring far inland to Vienna, Bern, and the Mediterranean. Customshouses high in the Alps stank of fish from distant oceans. Along the English coast great fairs arose that trafficked in millions of fish. Herring rapidly became a staple, not only on aristocratic and monastic tables but in poorhouses and cities. Herring nourished armies in an era of endemic warfare. Between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries, the European herring industry expanded rapidly, first in the hands of the Hanseatic League, then on an industrial scale with the Dutch, who took processing operations offshore in factory ships. But it was a local industry conducted mainly in shallow waters.

The Norse were the first to voyage deep into the Western Ocean. For thousands of years, the Lofoten Islanders of northern Norway had harvested white-fleshed cod, drying it in the sunshine and cold winds of late winter and spring. Dried stockfish, light and easy to transport, was the perfect staple for Norse ships coasting deep into the Baltic, raiding England and France, and sailing westward to Iceland and beyond. The Norse could not have sailed to Iceland, Greenland, and North America without stockfish, which enabled them to survive at sea for weeks on end.

Their voyages came during the Medieval Warm Period, a time when temperatures were at least as warm as today and ice conditions in the north were favorable for offshore voyaging. Until about 1250, ships could sail readily between Iceland and Greenland. With the onset of the Little Ice Age, however, skippers had to sail farther south and west to avoid the pack ice. At the same time (and here we are venturing onto untrodden scientific ground) changes in water temperature and the pressure gradients of the North Atlantic Oscillation must have affected the distribution of both cod and herring, though the precise relationship is little understood.

The great Norse voyagers sailed to Greenland and beyond in search of new places to settle and out of a wanderlust that was an integral part of a restless, violent society. They carried stockfish far and wide, and it proved a more palatable substitute for salted herring on holy days. A huge stockfish industry developed, centered on Bergen, where Hanse ships exchanged grain for dried fish. Archaeological excavations in the Lofoten Islands have pinpointed the moment around the eleventh century when cod became a lucrative trading commodity that supplanted herring on many dinner tables.