Also by Brian Fagan

Floods, Famines and Emperors: El Nino and the Collapse of Civilizations

Into the Unknown

From Black Land to Fifth Sun

Eyewitness to Discovery (editor)

Oxford Companion to Archaeology (editor)

Time Detectives

Kingdoms of Jade, Kingdoms of Gold

Ancient North America

Journey from Eden

The Great Journey

The Adventure of Archaeology

The Aztecs

Clash of Cultures

Return to Babylon

Quest for the Past

Elusive Treasure

The Rape of the Nile

Southern Africa

How CLIMATE MADE HISTORY 1300-1850

BRIAN FAGAN

Professor Glyn Daniel and Ruth Daniel, archaeologists

Professor Hubert Lamb, climatologist

We are in a raft, gliding down a river, toward a waterfall. We have a map but are uncertain of our location and hence are unsure of the distance to the waterfall. Some of us are getting nervous and wish to land immediately; others insist we can continue safely for several more hours. A few are enjoying the ride so much that they deny there is any immediate danger although the map clearly shows a waterfall. How do we avoid a disaster?

-George S. Philander, Is the Temperature Rising?

April 1963: The waters of the Blackwater River in eastern England were pewter gray, riffled by an arctic northeasterly breeze. Thick snow clouds hovered over the North Sea. Heeling to the strengthening wind, we tacked downriver with the ebb tide, muffled to our ears in every stitch of clothing we had aboard. Braseis coursed into the short waves of the estuary, throwing chill spray that froze as it hit the deck. Within minutes, the decks were sheathed with a thin layer of ice. Thankfully, we turned upstream and found mooring in nearby Brightlingsea Creek. Thick snow began to fall as we thawed out with glasses of mulled rum. Next morning, we woke to an unfamiliar arctic world, cushioned with silent white. There was fifteen centimeters of snow on deck.

Thirty-five years later, I sailed down the Blackwater again, at almost the same time of year. The temperature was 18C, the water a muddy green, glistening in the afternoon sunshine, skies pale blue overhead. We sailed before a mild southwesterly, tide underfoot, with only thin sweaters on. I shuddered at the memory of the chilly passage of three decades before as we lazed in the warmth, the sort of weather one would expect in a California spring, not during April in northern Europe. I remarked to my shipmates that global warming has its benefits. They agreed.

Humanity has been at the mercy of climate change for its entire existence. Infinitely ingenious, we have lived through at least eight, perhaps nine, glacial episodes in the past 730,000 years. Our ancestors adapted to the universal but irregular global warming since the end of the Ice Age with dazzling opportunism. They developed strategies for surviving harsh drought cycles, decades of heavy rainfall or unaccustomed cold; adopted agriculture and stock-raising, which revolutionized human life; founded the worlds first preindustrial civilizations in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Americas. The price of sudden climate change, in famine, disease, and suffering, was often high.

The Little Ice Age survives only as a dim recollection: depictions in school textbooks of people dancing at fairs on a frozen River Thames in London in the jolly days of King Charles II; legends of George Washingtons ragtag Continental Army wintering over at Valley Forge in 1777/78. We have forgotten that only two centuries ago Europe experienced a cycle of bitterly cold winters, mountain glaciers in the Swiss Alps were lower than in recorded memory, and pack ice surrounded Iceland for much of the year. Hundreds of poor died of hypothermia in London during the cold winters of the 1880s, and soldiers froze to death on the Western Front in 1916. Our memories of weather events, even of exceptional storms and unusual cold, fade quickly with the passing generations. The and statistics of temperature and rainfall mean little without the chill of cold on ones skin, or mud clinging to ones boots in a field of ruined wheat flattened by rain.

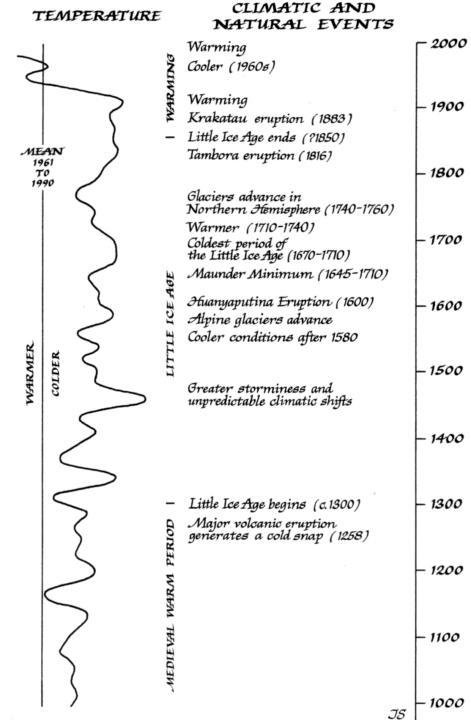

We live in an era of global warming that has lasted longer than any such period over the past thousand years. For the first time, human beings with their promiscuous land clearance, industrial-scale agriculture, and use of coal, oil, and other fossil fuels have raised greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere to record highs and are changing global climate. In an era so warm that sixty-five British bird species laid their eggs an average of 8.8 days earlier in 1995 than in 1971, when brushfires consumed over 500,000 hectares of drought-plagued Mexican forest in 1998 and when the sea level has risen in Fiji an average of 1.5 centimeters a year over the past nine decades-in such times, the weather extremes of the Little Ice Age seem grotesquely remote. But we need to understand just how profoundly the climatic events of the Little Ice Age rippled through Europe over five hundred momentous years of history. These events did more than help shape the modern world. They are the easily ignored, but deeply important, context for the unprecedented global warming today. They offer precedent as we look into the climatic future.

Speak the words ice age, and the mind turns to Cro-Magnon mammoth hunters on windswept European plains devoid of trees. But the Little Ice Age was far from a deep freeze. Think instead of an irregular seesaw of rapid climatic shifts, driven by complex and still little understood interactions between the atmosphere and the ocean. The seesaw brought cycles of intensely cold winters and easterly winds, then switched abruptly to years of heavy spring and early summer rains, mild winters, and frequent Atlantic storms, or to periods of droughts, light northeasterlies, and summer heat waves that baked growing corn fields under a shimmering haze. The Little Ice Age was an endless zigzag of climatic shifts, few lasting more than a quarter century. Todays prolonged warming is an anomaly.

Reconstructing the climate changes of the past is extremely difficult, because reliable instrument records are but a few centuries old, and even these exist only in Europe and North America. Systematic weather observations began in India during the nineteenth century. Accurate meteorological records for tropical Africa are little more than three-quarters of a century old. For earlier times, we have but what are called proxy records reconstructed from incomplete written accounts, tree rings, and ice cores. Country clergymen and gentleman scientists with time on their hands sometimes kept weather records over long periods. Chronicles like those of the eighteenth-century diarist John Evelyn or monastery scribes are invaluable for their remarks on unusual weather, but their usefulness in making comparisons is limited. Remarks like the worst rain storm in memory, or hundreds of fishing boats overwhelmed by mighty waves do not an accurate meteorological record make, even if they made a deep impression at the time. The traumas of extreme weather events fade rapidly from human consciousness. Many New Yorkers still vividly remember the great heat wave of Summer 1999, but it will soon fade from collective memory, just like the great New York blizzard of 1888, which stranded hundreds of people in Grand Central Station and froze dozens to death in deep snowdrifts.