BEGINNINGS (C. 6 TO 2 MA)

DOI: 10.4324/9781003177326-1

About 3.7 million years ago, a volcano named Sadiman in Tanzania, East Africa, erupted with a cloud of fine ash. The cascading volcanic dust fell in a thin layer on the surrounding landscape at Laetoli. Then light rain fell, creating a soft, cement-like pathway in a seasonal river that led to nearby waterholes. Dozens of now-extinct animals walked along the riverbed soon afterwardelephants, saber-toothed tigers, and antelope. Another subsequent eruption sealed the hardened surface with its footprints, which included those of two human ancestors. Trailing behind them, often stepping directly into the adult footprints, are those of a child.

We have but an indirect sketch of the walkers. The imprints came from individuals between 1.4 and 1.49 meters tall. They walked with a rolling, slow-moving gait, their hips swiveling with each step, very different from the free-standing gait of modern humans. Their footprints display well developed arches, with heel and toe prints that could only have been made by someone walking on two feetvery different from those of upright chimpanzees.

The Laetoli footprints provide a glimpse of early hominins and, their discovery in the 1970s, led to the bombshell realization that bipedalism (walking on two feet) preceded growth in brain size, and not the other way round. Researchers realized that upright walkingmeant our hands were now free. This meant we could make thingsand creativity is a key attribute of our human family.

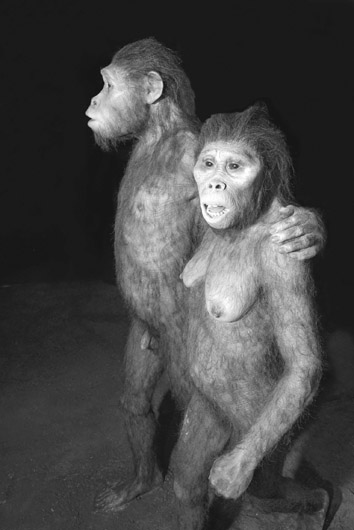

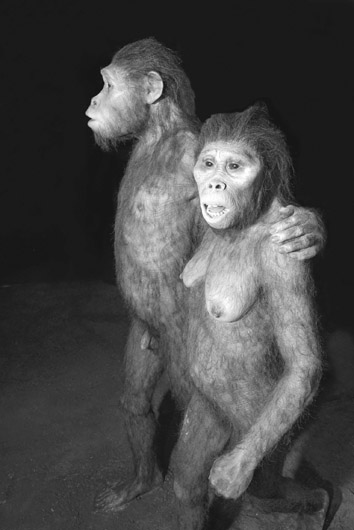

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.1 A replica of two australopithecines leaving footprints in lava, 3.7 Ma.

Martin Shields/Alamy Stock Photo

HOMINIDAE AND HOMININI

First, some genealogy. We humans are members of the order Primates, which includes two suborders, one of which includes the Anthropoids, which incorporates apes, people, and monkeys. Further up the genealogical pyramid, we belong to the superfamily Hominoidea, which also includes gibbons, gorillas, chimpanzees, and the bonobo. Within the hominoid superfamily, theres a division between Hominidae, which includes African and Asian apes, as well as us. We belong to the Hominini (or hominin) tribe, which includes modern humans, earlier human subspecies, and their direct ancestors.

To date, researchers have identified over 20 hominin species, but only some of them are our ancestors, many becoming extinct without giving rise to new species. At any given time over much of the past six million years, several hominin species co-existed. (A species is typically defined as a group of organisms that can provide fertile offspring.) It was only after around 30,000 years ago, that the other human species became extinct and only weHomo sapiensremained. But, given the scanty archaeological record for the early period, how do we know when hominins separated from non-human primates?

IN THE BEGINNING

By 14 Ma, Africas climate was much drier than in earlier times. Hard-fruit and grass-eating hominoids flourished throughout East Africa between 8 and 5 Ma. They spent much time on the ground but walked on four feet. Unfortunately, we know almost nothing about these hominoids. They lived at a time of major environmental changes, including cooler temperatures and more open, as opposed to wooded, terrain. Todays humans are the descendants of these generalized common hominoid ancestors. As forests retreated and tropical Africas climate became drier, they adapted to much more open savanna environments.

This was when early hominins became bipedal, perhaps because they spent more time feeding off foods on the ground. Bipedalism meant that walking assumed great importance for foraging over wider areas.

In adapting to drier environments, early hominin populations with their bipedalism could cover longer distances and had improved endurance. Apes, which were adapted to forested environments, stayed in the trees. In contrast, bipedal hominins, who potentially evolved around 6 Ma, expanded the range of territory where they obtained food. They broadened their diets, now including more meat.

The long-term solutions to living in the savanna meant exploiting patchy and widely distributed foods, while depending on reliable, and often hard-to-find, water supplies. The hominins were constantly on the move, with meat now playing a more important role during seasons when plant foods were scarce.

Most experts believe that East Africa was the main center of early human evolution. It is here that the greatest number of early hominins have come to light. But future fossil discoveries may complicate this scenario. The now-desert environments of Ethiopia and northern Kenya were open savanna grassland and woodland that teemed with herds of antelope and other mammals. These were prey for lions, leopards, and other predators, and also for our early hominin ancestors. We know almost nothing of these hominins, except the little known, probably bipedal, Orrronin tugenensis, who lived about 6.5 to 5.6 Ma. There is also Sahelanthropus tchadensis, of Central African origin. The latter may date to 76 Ma, which would place it at around the time of the likely divergence of the hominin lineage with that of the chimpanzee.

The date of this split depends less on the spartan fossil evidence, and more on genetic analysis of modern humans and modern chimps. By recording the amount by which the genes of the two species have diverged, geneticists theorize the time of our split. This method of timing, known as the molecular clock, is based on a number of assumptions, which are constantly refined. And while there is disagreement over the precise date of our split, most geneticists currently put it somewhere between 8 and 6 Ma. As to the hominins that lived at the dawn of our story, certainly the two species referred to above were potentially bipedal (a defining characteristic of the hominin) yet they were also tree climbers.

ARDIPITHECUS RAMIDUS (4.5 MA)

As the centuries turned into millennia, other hominin species undoubtedly came and went, such as humans.

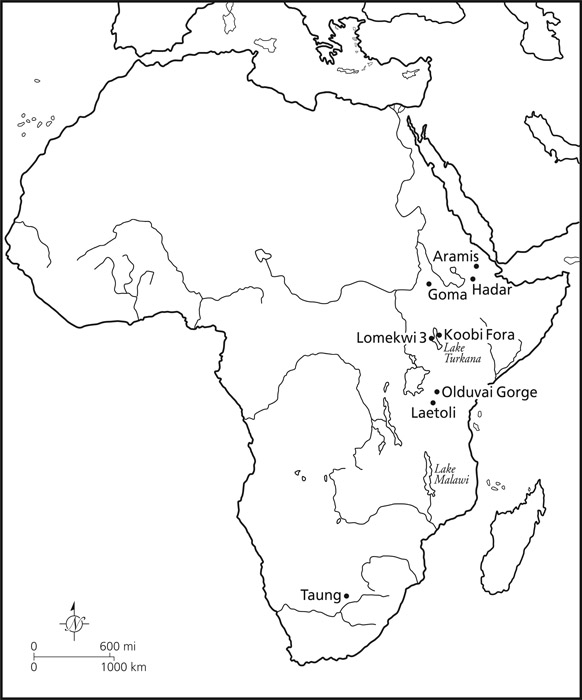

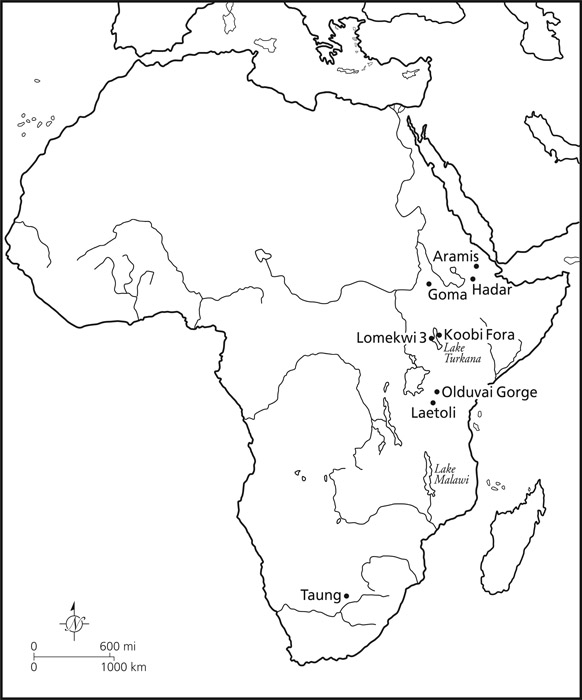

Map showing early sites in Africa.

Ardipithecus ramidus was not the only hominin in East Africa at the time. Most likely, they were the base grade from which later hominins evolved. But the exact relationship between Ardipithecus and later human ancestors is still a mystery.

AUSTRALOPITHECUS AFARENSIS: THE SOUTHERN APE FROM AFAR (C. 3.9 TO 2.9 MA)

After hundreds of thousands of yearsand were talking about long timescales hereone of the best known australopithecines emerged; Australopithecus afarensis. It may be the ancestor of the genus Homo, to which modern humansusbelong.

Australopithecus afarensis has already appeared in this story, thanks to its footprints at Laetoli in Tanzania. These hominins are best known from the Hadar region of Ethiopia, famous for Maurice Taieb and Donald Johansons discovery of a 3.18-million-year-old incomplete skeleton that they named Lucy. (They were playing the Beatles song, Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds when they celebrated their discovery.) She was only 1.0 to 1.2 meters tall and between 19 and 21 years old.

Subsequent finds have filled in the picture. There was a marked difference between males and much smaller females. But all were powerful, heavily muscled, and fully bipedal. A 3.2 Ma foot found near Lucys find-spot had arches, showing that

Figure 1.1 A replica of two australopithecines leaving footprints in lava, 3.7 Ma.

Figure 1.1 A replica of two australopithecines leaving footprints in lava, 3.7 Ma.  Map showing early sites in Africa.

Map showing early sites in Africa.