Acknowledgements

I would like to thank three people all called David, as chance would have it. My two friends David Morgan and David van Oss read this in manuscript form and gave me both stern criticism and encouragement, both equally important. My uncle, David Gosden, took me to the hillfort on Cold Kitchen Hill and to the excavations at South Cadbury when I was young and gave rise to my earliest interest in prehistory. Readers may have their own opinions as to whether he is to be thanked or blamed for this, but I am very grateful for it.

Chapter 1

What and when is prehistory?

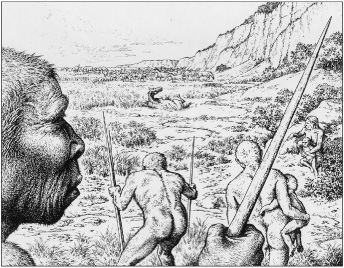

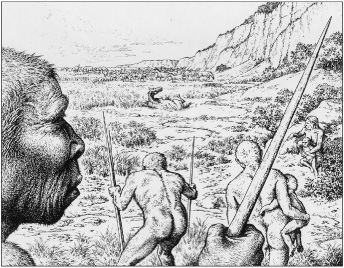

On the plain there lay a horse. Clustered tightly around it was a group of creatures intent on what they were doing; some watched the group of hyenas circling the dead animal, occasionally throwing stones to keep them off. Some still held their wooden spears.

Six had their heads down, working flint. They had already prepared some of the great nodules of local flint from the nearby sea cliff by taking off flakes to give the rough shape of a handaxe and now each was working a prepared chunk with great speed and skill. The other scavengers and predators kept away: they had tangled with these creatures before and learnt to keep a distance. As soon as the first knapper had finished the razor-sharp artefact that we now call a handaxe, they scrambled on to the horse carcass and began to cut the meat. Joints were taken from the legs and haunches and once the bones had been revealed the larger ones were smashed to extract the marrow. Let us imagine that the adults helped to feed the kids and the young aided the old, although the weaker members may have had to grab what they could. Some meat was consumed on the spot, the choicer joints were taken to the top of the cliff where the group had a base and consumed at leisure. Let us imagine again that they could relax now for a day or two, replace their spears, make a new hammer for flint working from a suitable horse bone, and play with their children.

1. The Boxgrove hominids hunt a horse

This happened at a place which half a million years later would be known as Boxgrove, near Chichester in southern England. None of the creatures involved had the remotest awareness that traces of their activities would survive for half a million years, preserved by rapid burial under collapsing cliff sediments. No words survive to tell us of this and countless other incidents, but we can give voice to questions aplenty. Because Boxgrove is an extraordinary site there is a surprising number of things we can know with certainty. Beautifully detailed excavation and recording of the site has shown six (or perhaps seven) discrete areas of flint working where the handaxes were fashioned. Dealing with a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle, archaeologists have worked in reverse order to the earlier hominids and, rather than breaking down a big nodule of flint into small flakes and a large handaxe, they have put the flakes back together again to create a complete nodule with only one missing middle element the handaxe itself. A void is left in the centre of the stone reminding us that in some parts of the world more recent stone knappers have seen their task as not making a stone tool, but rather freeing it from its encasing stone material. Once freed these particular handaxes have so far eluded archaeological detection, although they may lie in another part of the same site, discarded by a meat-bloated creature moving off to rest somewhere safe. Indeed many dozens of near-pristine handaxes have been recovered from Boxgrove, some with microscopic traces that indicate they were used for butchery.

The horse bones themselves tell their own story. This was the largest true horse species ever found in Britain, for a start, making a very attractive quarry for a hunting band. The horse bones that lie scattered amongst the flint debris show evidence of butchery in the form of thin scores into the surface of the bone resulting from the process of filleting to remove blocks of meat and muscle. The bones are smashed, probably with flint hammers, for marrow extraction. Microscopic examination shows the marks of animal teeth, with hyenas moving in after the hominids had left. We can tell which order various creatures got to the carcass as the teeth marks gouged across existing flint butchery marks, hyenas coming in to crunch the bone (and incidentally to scatter some of the flint debris a little in the process) after the hominids had left. In this set of coastal communities hyenas were not top dog and although working in a socially organized fashion themselves could not compete with the tools, intelligence, and organization of the hominids.

How do we know that these creatures had spears? Here we enter an area of slightly less certain inference. One scapula (shoulder blade) of the horse has a perfectly circular hole, which, on the basis of comparisons with holes made experimentally on modern skeletons, could probably only have been made by a pointed object travelling at a high velocity. This is not inconsistent with a spear thrown from a distance hitting the horse at considerable speed. Why use such equivocal language? The trivial reason is that the horse bone is somewhat chalky and flaky after its 500 millennia of burial, raising questions about the nature of the hole and how it got there, but really there is little doubt about the identification of the wound. The more important reason is that a lot hangs on whether these creatures hunted or not. Many have said that hunting only developed with fully modern humans some 50,000 years ago and in earlier times there was not the social cohesion, technology, or wit to do more than scavenge the kills of large carnivores or gather plant foods. To bring down, kill, and butcher a large fit horse is no easy task and makes us think about the nature of group organization, levels of physical skills, and mental acuity. It is not something most of us would like to do armed only by stone age technology.

Our humanity resides in social cooperation and a flexibility of mental and physical response to the world and we are fascinated by the origins of all these abilities. For creatures half a million years ago to appear to possess many of the things that make us human causes us to reflect on some of the deeper questions of human existence. These creatures were rather different to us in physical form, so what is the link between the nature of bodies and brains (biology, in short) and culture? Their range of material culture (at least that which survives) appears to lack elements of decoration and style we would associate with all modern material culture known from the last 50,000 years. Does this matter? Does it signal a less rounded and deep appreciation of the material and social worlds? Does the lack of apparent stylistic and symbolic content of their material culture indicate that these creatures lacked the most sophisticated symbolic system of all language? Were gestures, grunts and the sharing of food all that passed between them? Or did they sit and discuss the killing of the horse for weeks and months afterwards? Of course we do not know and will never know for sure, but these are the questions that most interest us.

Archaeological excavation is often described as moving from the known to the unknown; working from deposits and sequences on areas of the site which are well understood to those which are not. The process of inference that creates prehistory moves in a similar sequence. We start from the nature of knapping and butchery debris, which methods of reconstruction developed over the last century allow us to understand with some certainty. We then move from the reconstructed flint nodule with the ghost of a handaxe at its heart to the manual actions which produced it, the use of the missing tool for cutting up the horse, to the nature of social and physical skills lying behind these acts and on to their individual and social consequences. Prehistorians need to exercise extreme vigilance, both for themselves and for others, as to when they cross the line between being reasonably sure about something into less directly grounded inference. The issues we are driven to understand lie always in the areas of least uncertainty, so that too cautious an approach will leave us grounded in the fascinating but ultimately trivial world of stone tool technologies or butchery practices. We can throw caution to the winds, especially in a synthetic volume such as this, pursuing the big picture, straying increasingly far from the secure inferences that stone or bone analysts can provide, exciting their rightful scorn There is no way you can be sure of