Kavan - Asylum piece

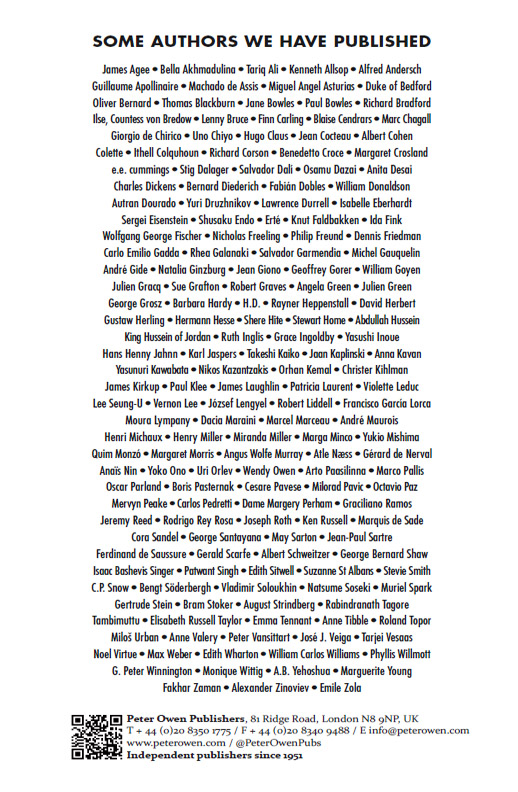

Here you can read online Kavan - Asylum piece full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: London, year: 2001, publisher: Perseus Books Group;Peter Owen, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Asylum piece: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Asylum piece" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Asylum piece — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Asylum piece" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

ASYLUM PIECE

This collection of stories, mostly interlinked and largely autobiographical, chart the descent of the narrator from the onset of neurosis to final incarceration in a Swiss clinic. The sense of paranoia, of persecution by a foe or force that is never given a name, evokes The Trial by Kafka, a writer with whom Kavan is often compared, although her deeply personal, restrained, and almost foreign accented style has no true model. The same characters who recur throughout the protagonist's unhelpful adviser, the friend and lover who abandons her at the clinic, and an assortment of deluded companions are sketched without a trace of the rage, selfpity, or sentiment that have marked more recent accounts of mental instability.

ANNA KAVAN, nee Helen Woods, was born in Cannes probably in 1901; she was evasive about the facts of her life and spent her childhood in Europe, the USA and Great Britain. Twice married and divorced, she began writing while living with her first husband in Burma and was published under her married name of Helen Ferguson. In the wake of the collapse of her second marriage, she suffered the first of many nervous breakdowns and was confined to a clinic in Switzerland; she emerged from her incarceration with a new name Anna Kavan, the protagonist of her 1930 novel Let Me Alone an outwardly different persona and a new literary style. Her first novel in this guise was Asylum Piece, and it achieved for her a certain recognition.

She was a long-term heroin addict and suffered periodic bouts of mental illness, and these facets of her life feature prominently in her novels and short stories. She died in 1968 of heart failure soon after the publication of her most celebrated work, the novel Ice.

The Birthmark

THE BIRTHMARK

When I was fourteen my fathers health made it necessary for him to go abroad for a year. It was decided that my mother should accompany him, our home was temporarily closed, and I was sent to a small boarding school in the country.

At this school I got to know a girl called H. I purposely use the words got to know in preference to the words made friends with, because, although I was acutely conscious of her all the time I remained there, no actual friendship developed between us.

It was at supper time on my first day at the school that H first caught my attention. I was sitting beside another new girl at the long table, feeling strange and subdued and a little homesick in this noisy environment so different from the enclosed, intimate atmosphere in which the whole of my life had been passed up to that day. I looked at the young faces of these still unknown companions, some of whom were to become friends, some enemies. One face among them all held my eyes with compelling attraction.

H was sitting on the opposite side of the table, almost immediately facing me. In the midst of so many brown heads her fairness alone was arresting. It was an autumn evening, misty and cold, and the room was not too well lighted. I had the impression that what light there was in the dining hall clustered around her, reviving and renewing itself as it played upon her fair hair. In looking back I think that she must have been beautiful; yet the detailed picture of her obstinately eludes me, I can recall only an impression of a face unique, neither gay nor melancholy, but endued with a peculiar quality of apartness, the look of a person dedicated to some accepted destiny. Perhaps these phrases sound out of place in connection with a schoolgirl who was only a few months older than I; and naturally I did not think of her in that way at the time. It is the accumulated rather than the momentary impression which I want to convey. Just then I saw only a fair girl, slightly my senior, who, catching my eyes upon her and doubtless thinking that I might be in need of encouragement, smiled at me across the table.

I remember that I looked back at her with some envy. It seemed to me then that she must possess everything that I, as a newcomer, lacked success, popularity, an established place in the school world. Afterwards I found out that this was not quite the case. A curious shade seemed to dim all Hs activities. I came to look upon this shadow, so hard to describe in words, as being in some way the complement of her rare outward brilliance.

How can I convey the strange sense of nullification that accompanied her? Although she was not unpopular, she had no intimate friends; and although she was in the first rank both as regards work and sport, some inevitable accidental happening always debarred her from supreme achievement. This fate she seemed to accept without question: almost, one would have thought, without being aware of it. I never heard her complain of the bad luck which so consistently robbed her of every prize.

And yet she was certainly neither indifferent nor unaware.

I recall very clearly an occasion towards the end of my time at school. In one of the corridors was a baize-covered board to which, among other notices, was fastened a large sheet of paper bearing our names and the number of marks which each of us received every week. H was standing in front of this list, quite alone, looking at it with an expression that I did not understand, an expression not of resentment, not of regret, but, so it seemed to me, of resignation combined with dread. Seeing that look on her face I was overcome by a wave of passionate and inexplicable compassion; an emotion so profound, so apparently unjustified by the circumstances, that I was astonished to feel tears in my eyes.

Let me help you ... Let me do something, I heard myself imploring, inarticulate as though my own fate were at stake.

Instead of answering me, H rolled up one of her sleeves and silently pointed to a blemish on her upper arm. It was a birthmark, faint as if traced in faded ink, which at first sight seemed to be no more than a little web of veins under the skin. But as I examined it more closely I saw that it resembled a medallion, a miniature design, a circle armed with sharp points and enclosing a tiny shape very soft and tender perhaps a rose.

Have you ever seen that anywhere else? she asked me; and it crossed my mind that she hoped that I too bore a similar mark.

Was it disappointment, embarrassment or despair that appeared on her face as I reluctantly shook my head? I only know that she hurried out of the corridor and that for the rest of the time I was at school she seemed to avoid me and that we were never alone together again.

The years passed, and though I heard nothing about H, I never really forgot her. Every now and then, once or twice a year, when I was in a train, or waiting for an appointment, or getting dressed in the morning, the thought of her would come to me, together with a peculiar discomfort, a kind of spiritual unease which I would banish as soon as possible.

One summer I was travelling in a foreign country, and, owing to an alteration in the railway timetable, I found myself obliged to change trains at a small lake-side town. As I had three hours to wait, I left the station and went out into the streets. It was an August afternoon, very hot and sultry, ominous thunder clouds were boiling up over the high mountains. At first I thought I would go down to the lake in search of coolness, but something ill-omened in the aspect of that stagnant sheet of lava-coloured water repelled me, and I decided instead to visit the castle which was the principal feature of the place.

This ancient fortress was built at the highest point of the town and was clearly visible from the square in front of the station. It seemed to me that I had only to walk up any one of the steep streets leading in that direction to reach it in a few moments. But my eyes must have deceived me as to the distance, for it turned out to be quite a long walk. Arriving hot, tired and unaccountably depressed at the great studded gates, I almost decided not to enter, but a group of tourists was just going inside and I allowed the guide to persuade me to join them.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Asylum piece»

Look at similar books to Asylum piece. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Asylum piece and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.