This collection of stories, mostly interlinked and largely autobiographical, chart the descent of the narrator from the onset of neurosis to final incarceration in a Swiss clinic. The sense of paranoia, of persecution by a foe or force that is never given a name, evokes The Trial by Kafka, a writer with whom Kavan is often compared, although her deeply personal, restrained, and almost foreign accented style has no true model. The same characters who recur throughout the protagonist's unhelpful adviser, the friend and lover who abandons her at the clinic, and an assortment of deluded companions are sketched without a trace of the rage, selfpity, or sentiment that have marked more recent accounts of mental instability.

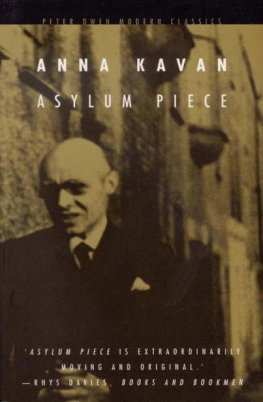

ANNA KAVAN, nee Helen Woods, was born in Cannes probably in 1901; she was evasive about the facts of her life and spent her childhood in Europe, the USA and Great Britain. Twice married and divorced, she began writing while living with her first husband in Burma and was published under her married name of Helen Ferguson. In the wake of the collapse of her second marriage, she suffered the first of many nervous breakdowns and was confined to a clinic in Switzerland; she emerged from her incarceration with a new name Anna Kavan, the protagonist of her 1930 novel Let Me Alone an outwardly different persona and a new literary style. Her first novel in this guise was Asylum Piece, and it achieved for her a certain recognition.

She was a long-term heroin addict and suffered periodic bouts of mental illness, and these facets of her life feature prominently in her novels and short stories. She died in 1968 of heart failure soon after the publication of her most celebrated work, the novel Ice.

I was introduced to Anna Kavan and to her work in 1956 by a mutual friend, Diana Johns, who ran a bookshop which Anna frequented. This was shortly after publication of her novel A Scarcity of Love. Following the book boom of the late forties Anna had found it increasingly difficult to find publishers for her work, and her reputation, which had seemed secure, was declining. Lacking any offers for A Scarcity of Love, she partly subsidised its publication; but the publisher, an acquaintance of hers on the periphery of book publishing, lacked distribution facilities and failed to pay his printer. His subsequent bankruptcy prevented even a moderate circulation of the book which my firm successfully reissued in 1971.

Anna, who was then living in a beautiful house which she had converted in Peel Street, Kensington, was in the throes of litigation with the builders: Showing me their slovenly work, she explained that she was obliged to convert houses to supplement the small income bequeathed to her by her wealthy mother. She told me that she was a compulsive writer and was only happy when writing. During this first visit of mine, she handed me the manuscript of a new novel, Eagles Nest. We published this book in 1957 and, despite poor sales, followed it with a volume of stories, A Bright Green Field, the next year.

Anna Kavan was a lonely person, aloof with strangers, who relaxed only among a few intimate friends. Her regular visitors included the writer Rhys Davies and a doctor called Blut. Sometimes I visited her for drinks or dinner. She was an excellent hostess and a good cook. It was some time before I realised that she was an incurable heroin addict; this was not evident either in her behaviour or in her smart appearance.

In about 1960 she completed a short novel which was good, but it seemed to me to be too short to make a book and at that time my firms imprint was not well enough established to allow deviation from the more conventional formats. Of course I gave her my reasons for rejecting it. A year or so later I reapproached her about the novella, since I now felt confident to publish it, only to be told that she had destroyed it after my rejection. It was around this time that she sold the Peel Street house and had built to her design another one nearby, which remained her home until her death. Occasionally she augmented her income by selling personal treasures, such as her Graham Sutherland painting, which saddened her. From time to time she sent me stories some of them were brilliant, whilst others fell below the general high standard she had set herself. Like many other writers, Anna was a bad judge of her own work. I thought it important that only her best writing should be published. Another novel appeared under the Scorpion Press imprint in the sixties.

In 1967 I agreed to publish Ice, after some revisions were made. This and some of her later stories which Encounter published were verging on science-fiction. When I remarked on this she replied: Thats the way I see the world now. The publication of Ice and of several stories in magazines helped restore her reputation to some extent. The editors of Encounter assumed that the stories I had sent them were by a talented new writer, and when her identity was revealed they commented: Is it the Anna Kavan? We thought she was dead! Anna kept her age a closely guarded secret. After the publication of Ice, having heard of her sale of the Sutherland, I suggested she might be eligible for an Arts Council grant. Her surprising reluctance to respond to my suggestion was later explained to me by Rhys Davies: she refused to divulge her date of birth on the application form.

I had known for some time that Anna was unwell but without appreciating the seriousness of her illness. Early in December 1968 my wife and I invited her to a housewarming party, and she said she hoped to come which rather surprised me, since as a rule she avoided social gatherings of this kind. Shortly after the party the police telephoned me, having found our invitation card in her house, which they had broken into at the request of Rhys Davies. She had died on the evening of our party.

The morning of her funeral I received the news that Doubleday, her American publishers of the forties, had bought Ice.

For the most part neglected in her lifetime, Anna Kavans posthumous reputation is growing. French and Dutch translations of her work are in progress; stories by her have appeared in leading British, American and Danish magazines; her books are becoming something of a cult. I believe this reissue of one of her early books, Asylum Piece, to be long overdue. First published in 1940, it was highly praised by critics and in a long commendatory review of it in the Sunday Times Sir Desmond MacCarthy wrote: There is a beauty about these stories which has nothing to do with their pathological interest, and is the result of art. Two or three, if signed by a famous name, might rank among the story-tellers memorable achievements. There is beauty in the stillness of the authors ultimate despair.

It is sad that writers whose vision transcends that of their contemporaries often remain unappreciated in their own lifetime.

Peter Owen

When I was fourteen my fathers health made it necessary for him to go abroad for a year. It was decided that my mother should accompany him, our home was temporarily closed, and I was sent to a small boarding school in the country.

At this school I got to know a girl called H. I purposely use the words got to know in preference to the words made friends with, because, although I was acutely conscious of her all the time I remained there, no actual friendship developed between us.

It was at supper time on my first day at the school that H first caught my attention. I was sitting beside another new girl at the long table, feeling strange and subdued and a little homesick in this noisy environment so different from the enclosed, intimate atmosphere in which the whole of my life had been passed up to that day. I looked at the young faces of these still unknown companions, some of whom were to become friends, some enemies. One face among them all held my eyes with compelling attraction.