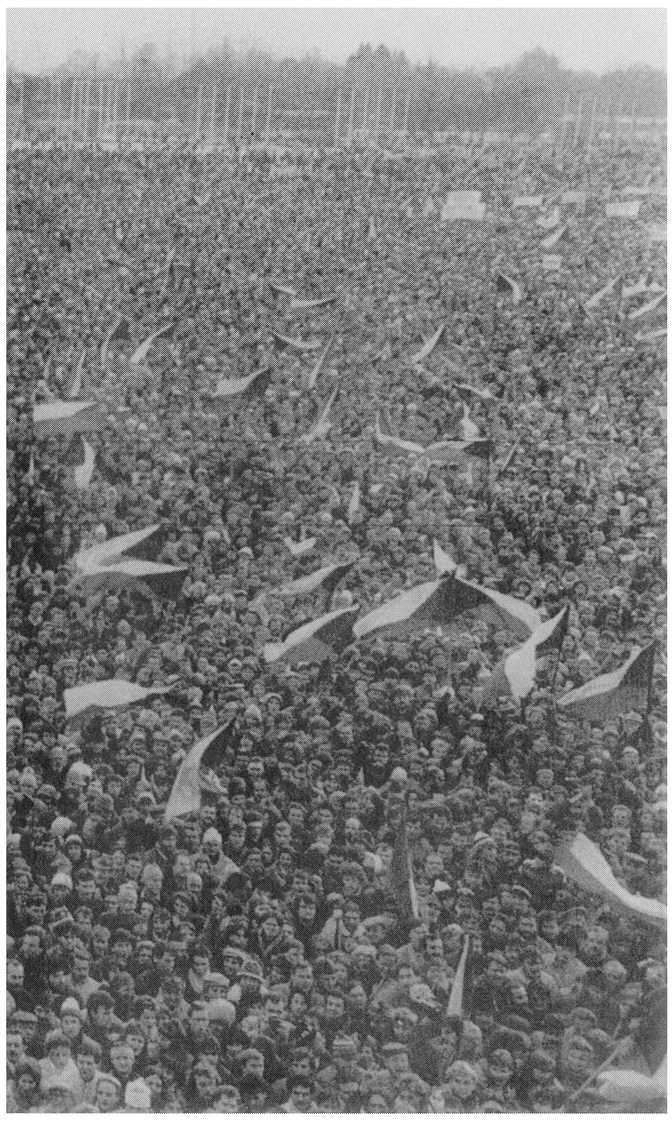

Many people contributed to this book in one way or another even before writing got under way, and we would like to express our gratitude to them. Our thanks go first to the British Council, which sent one of the authors off to Prague in November 1989 on a two-month postdoctoral fellowship to work on Czech-German relations. This was an opportunity to experience a revolution firsthand. The preparatory work for this book was assisted by the English Language Centre Educational Trust, which provided a small grant for a further two weeks in Czechoslovakia in May 1990.

Prof. Dr. Litsch, formerly director of the historical archive at the Charles University, Prague, donated a wide selection of runs of all daily newspapers for the weeks covering the revolution. Inenr Star and Pan Hrukov of the Prague Information Service and their staff at very short notice supplied the newspaper cuttings that formed the basis of a significant section of . In addition, thanks go to Dr. Svato, also of the historical archive, and to Dr. Petr Kuera, member of Parliament and adviser to the president, who found time to discuss aspects of the post-Communist government and Citizens Forum when more important matters were pressing.

Dr. Vladimr Kaiser, director of the county archive in st nad Labem, and Dr. Kristina Kaiserov reported on their experiences during the revolution in northern Bohemia. Vlasta Jaro of Most kept information flowing from the Teplice, Most, and Litvinov regions and likewise from local and regional newspapers. Petr Nmec, an erstwhile employee of the Semafor Revue Theater in Prague, provided contacts with members of the theatrical community (especially at the Vinohrady Theater) who were personally involved in the revolution from the very outset. Jenk Jaab, then a final-year student at the medical faculty, offered the benefit of his experience as an organizer of a so-called circle during the crucial first weeks.

In addition to newspapers, the media, and records of personal experiences, We would like to express our appreciation for the help given by all the people who worked downstairs, especially to Tom Cejp, an artist who manned the improvised archive single-handed. In difficult circumstances, he provided originals and photocopies of all available documents of Citizens Forum and the students, letters from the public, and protests from the basic organizations of the Communist party and the trade union movement; he also donated a complete run of Citizens Forum's alternative newspaper, Informan servis, from the first four weeks of the revolution.

We also owe a debt of gratitude to Jan Kavan, who worked in the dissident movement for two decades and was a member of Parliament for Citizens Forum in Prague. His information was invaluable, especially for the chapters dealing with the new state. Ji Kappel's business experience helped us greatly in working out the complexities of the present economic conditions. Stephany Griffith-Jones of the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex also gave us the benefit of her knowledge of the economic reforms.

A word of thanks, too, to Vladimr Jirnek and Ji Lochman, whose cartoons adorned the walls and press publications in Prague during the revolution; a sampling of their work is reproduced in this book.

Finally, Romy Damian deserves a special vote of thanks. She did a great deal more than provide expert advice when the computer went down.

Bernard Wheaton

Zdenk Kavan

In both Czech and Slovak, the first syllable always carries the main stress, but the unstressed syllables are not neutralized as they are in English. Rather, each one is pronounced more or less clearly, whether stressed or not. Vowels are short unless marked with the diacritical or (over a u ) . Haeks (literally, little hooks) in effect soften consonants. An thus sounds like the "gn" in "monsignor"; like the "ch" in "chop"; like the "sh" in "shirt"; like the "zh" in "leisure." A d, t, or n before the vowels i and takes on a similar softness (that is, a t in such a case would become a "ty" sound as in the British pronunciation of "tune").

Certain consonants have an altogether different pronunciation from their English counterparts. The c is equivalent to the "ts" in "cats"; ch is much like the Scottish "ch" in "loch"; j is pronounced as is the "y" in "yes"; r is trilled. Perhaps the most difficult sound for a nonnative speaker is the , which is something like a compressed "rzh" (thus Dvok = DVOR-zhahk).

Following are a few examples:

Letn = LET-nah

Bat'a = BAT-ya

Dubek = DUP-check

Vclav = VAHTS-lahf

Bene = BEN-esh

- AR Association for the Republic (Sdruen pro Republiku, or SR)

- ASD Association of Social Democrats (Asociace Socilnch demokrat, or ASD)

- CCTU Central Council of Trade Unions (stedn rada odbor, or RO)

- CDA Citizens Democratic Alliance (Obansk demokratick aliance, or ODA)

- CDM Christian Democratic Movement (Slovak) (Kest ansk demokratick hnut, or KDH)

- CDP Citizens Democratic party (Obansk demokratick strana, or ODS)

- CDP(C) Christian Democratic party (Czech) (Kest ansk demokratick strana, or KDS)

- CEH Common European Home

- CF Citizens Forum (Obansk frum, or OF)

- CFP Farmers' party (esk strana zemdlc, or SZ)

- KD Kolben-Dank industrial plant

- CM Citizens Movement (Obansk hnut, or OH)

- Comecon Council for Mutual Economic Assistance

- CPBM Communist party of Bohemia and Moravia (Komunistick strana ech a Moravy, or KSM)

- CPC Communist party of Czechoslovakia (Komunistick strana eskoslovenska, or KS)