In terms of its origins, this book has evolved over a number of years. It consists of new material, together with revised and, in some cases, much extended versions of work previously published (sometimes in hard to find sources).

A few very short extracts from Chapter 1 are included in Art History Versus Aesthetics , ed. James Elkins (Routledge: London, 2006), 123128. Chapter 2 is a much extended version of a paper entitled Pictorial Space and the Possibility of Art, published in the British Journal of Aesthetics 48 (2008): 175192. Part of Chapter 4 was published as Painting, Abstraction, Metaphysics: Merleau-Ponty and the Invisible, in Symposium 8, no. 2 (2004): 114. Chapter 5 appeared as Transcendence and Sculpture in Painting, Sculpture, and the Spiritual Dimension: The Kingston and Winchester Papers, ed. Stephen J. Newton and Brandon Taylor (Oneiros: London, 2003), 123132. Chapter 6 is a much extended version of a paper entitled The Logic of Abstract Art published in The Structurist (Fall, 2008): 5863. Chapter 9 is a slightly revised version of a paper of the same title that was published in The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 66, no. 2 (2008): 161170.

Thanks are due to my assistant Carin Baban for her exemplary work in preparing the manuscript for publication.

Conclusion

Art History and Art Practice

Some Future Possibilities

To conclude, I shall develop some of the broader ramifications of the approach taken in this book.

It began by showing the limits of reductionist art history and theory. In turning away from arts aesthetic significance, such history has tended to fixate one-sidedly on the documentary functions of the image. Through marginalizing or excluding other approaches to art history, it represents the overwhelming of art by a western consumerist mentality.

The bulk of my text has not shown the restrictedness of this approach by critique. It has done so by opening up ways of thinking about art which emphasize the phenomenological depth of its creation and reception. Phenomenological depth is not a question of significant form. It goes far beyond itthrough showing what enables form to become significant.

This centres on the way in which the making of visual art concentrates and clarifies factors which are central to perception, and to self-consciousnesss relation to the visible world. These complex factors constitute the intrinsic meaning or significance of the visual arts.

I have also argued at length, that in order for this depth to engage our attention intuitively, the image must be enjoyable in aesthetic terms, i.e. in terms of the relation between its phenomenal structure and the mediums comparative history. When a work achieves this status, the images intrinsic significance becomes artistic meaning.

There is one major conclusion that can be drawn. It is that the reductionist tendency in art history misses out on what is, in effect, visual arts raison dtre . If art history is to avoid such distorted analytic one-sidedness, it must embrace the dimension of phenomenological depthat least in those cases where it is negotiating (directly or indirectly)issues concerning visual arts claim to enduring cultural worth.

In addition to this general normative context, phenomenological depth might be useful to art historical studies in two ways. The more ambitious one would be in sustaining comparative stylistic analysis as a key methodological strategy.

Such comparative art history means, in effect, looking at artistic styles in relation to one another across different cultural times and places. Such a method was practiced in a restricted formalist way by Wolfflin, who tended to reduce issues of style to categories of beholding. I hope to have gone beyond this by providing artistic creation-based concepts and strategies which clarify the character of specific artworks or oeuvres , in relation to key aspects of the medium of which they are an instance. Through such clarification, comparative art history overcomes formalism.

The second way in which phenomenological depth might inform work in art history is rather more piecemeal, and can be of use even for (otherwise) reductionist approaches. It involves identifying the way in which such depth-factors are brought about by, or can carry, historically specific meanings on top, in a way that allows the historically specific and the aesthetic to mutually complement one another.

Such identifications would not rival or compete with explanations of how the work(s) came to be produced and received in historical terms. Rather they would offer a few insights into how criteria of aesthetic formation might be linked to the more historically specific aspects of selected artists and/or works.

That being said, I am, of course, implying that this kind of connection may admit, also, of much more extensive development by scholars with expertise in both art history and philosophy. Such development would allow for a more balanced modus operandi in art history that allowed it to be enriched so as to avoid the dangers of social and/or semiotic reductionism.

In what follows, then, I shall consider a few speculative possibilities for linking phenomenological depth to some historically specific developments in the history of art.

First, Malevichs emphasis on Suprematisms relation to the plane. He argues that

All that we see has arisen from a colour mass turned into plane and volume, and any machine, house, man, table, they are all painterly volume systems.

Indeed,

Standing on the economic Suprematist surface of the square... I leave it to serve as the basis for the economic extension of lifes activity.

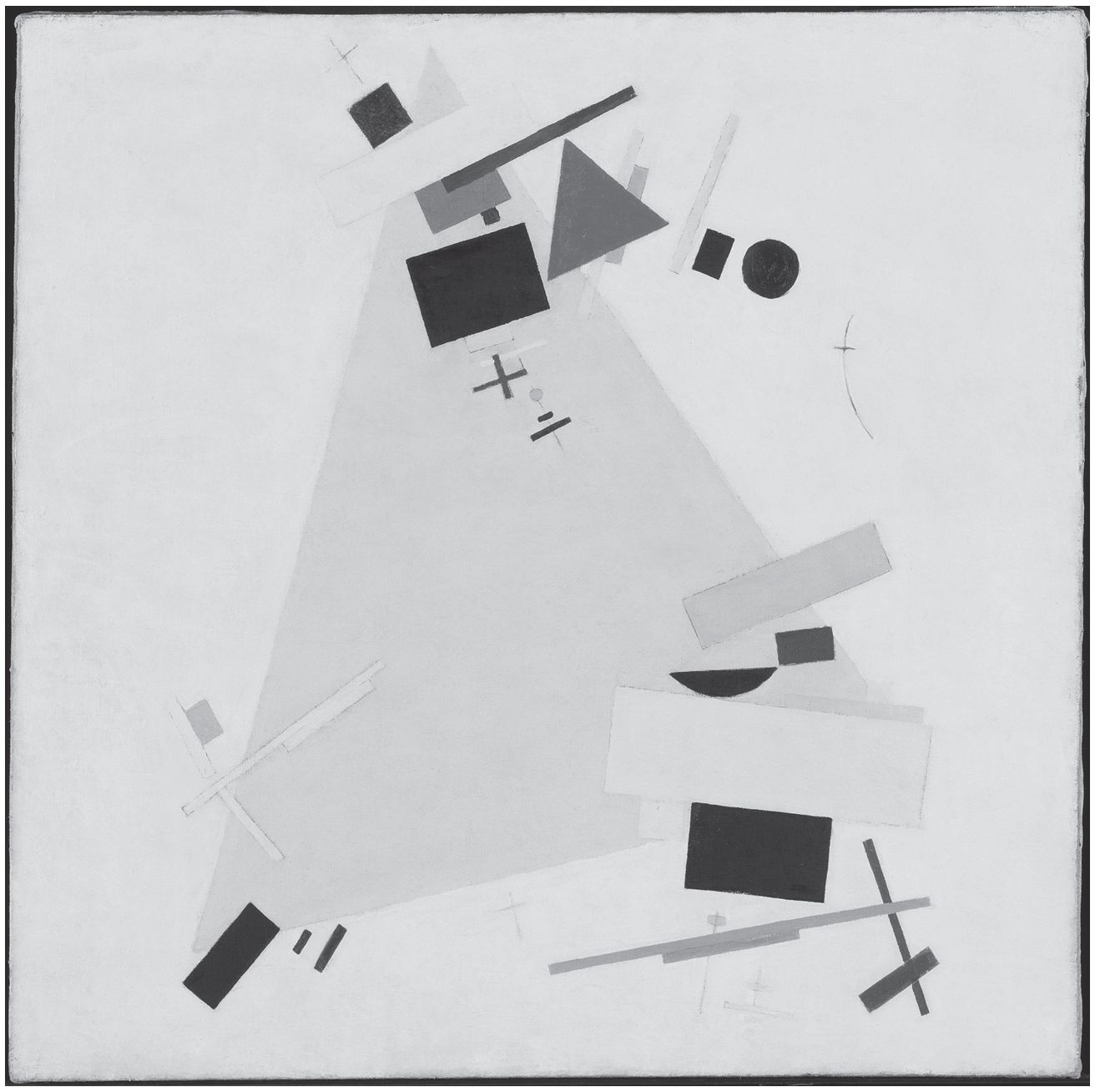

. Kazimir Malevich, Supremus No. 57 , ca. 1916. Oil on canvas, 80.2 x 80.3 cm. Tate Modern, London. Tate, London 2008.

In these remarks from 1919 Malevich is legitimizing abstract art in relation to the demands of the new Soviet state, and also utilizing complex Ouspenskian and Schopenhauerian ideas. However, this emphasis itself internalizes features which (in Chapter 6) I showed to be involved in a general theory of meaning for abstract art. There, it will be recalled, I emphasized optical illusion as the basis of this. In abstract art this is conventionalized in terms of associations which draw on that contextual space of things not noticed (or not noticeable) which subtends all visible things.

This includes visual configurations which arise from the destruction, deconstruction, reduction, reconstruction, or variation of familiar items, relations or states of affairs; and also structural aspects of spatial appearanceaddressed individually or in combination. (These aspects include colour, shape, mass, texture, density, volume, and changes of position.)

Now in his Suprematism, Malevich relates to this in an interesting way. The painting Supremus No. 57 , for example, involves a triangle which is tilted obliquely to the plane. This creates an optical tension which is amplified by a collection of various small geometric forms which constellate around each angle of the triangle.

Through this, the appearance of stasis and action is generated from the optical relation between real two-dimensional entities, rather than forms which allude to three-dimensional realities. Structures of spatial appearance are here expressed through a mode of optical illusion which (by virtue of being wholly constituted from real two-dimensional components) is more continuous with the level of our material existence, than are forms which invoke the third-dimension. This is because three-dimensional figures in a plane involve an additional level of illusion which is supervenient on the material reality of the two-dimensional base.