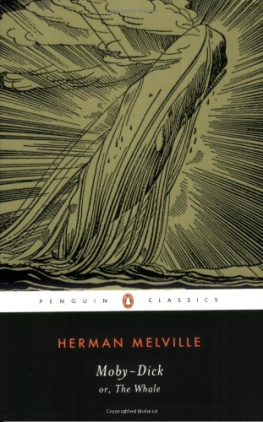

Melville and the visual arts : Ionian form, Venetian tint / Douglas Robillard.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-87338-575-6 (alk. paper)

1. Melville, Herman, 18191891KnowledgeArt. 2. Art and literatureUnited StatesHistory19th century. 3. Visual perception in literature. I. Title.

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available.

I F MELVILLE READ Frederic Henry Hedges Prose Writers of Germany (1848), and it seems likely enough that he would have read it, he knew the strictures that Gotthold Ephraim Lessing drew against literary pictorialism. In the preface to Laocoon, or the Limits of Poetry, as translated by Hedge, Lessing pointed out that false criticism misleads authors, and

has engendered a fondness for sketching in poetry and introducing allegory into painting. Men have attempted to make the former a speaking picture, without properly understanding what Poetry can or ought to paint; and to make the latter a silent poem, not considering in what degree Painting is capable of expressing universal conceptions, without departing too far from her destination and becoming a kind of arbitrary writing.

There is little doubt that Melville clearly understood Lessings complaint. But, having studied the matter deeply and seen what poets and prose writers had already accomplished, he no doubt felt secure in pursuing, with all his literary tact, the venture of making speaking pictures. And, in any case, Lessings battle had long since been lost. An article that Melville could have read, Lessings Laocon, probably by J. D. Whelpley, in American Review in 1851, discussed Lessings ideas at some length and concluded that Were the principles of our critic to pass into literature as critical canons, we conceive a great and serious injury would be inflicted upon the arts (19). There were already innumerable

Melvilles engagement with the art analogy is broad and exemplary in its persistence and is displayed throughout the whole range of his career. Pictorialism appears in some, though not all, of his prose fiction, in much of his poetry, and in a few of the attempts he made in literary and art criticism. His study of the various plastic arts was a crucial element in the development of his imaginative being. A whaleship may have been Ishmaels Yale College and Harvard, but Ishmaels creator did his advanced work in a larger, more productive theater of learning. Melville studiously attended picture galleries, exhibitions, and museums. His journals of 184950 and 185657 testify to the intensity of his interest. His collection of prints, gathered for years within the limits of a small income, gives a good idea of what he wanted to preserve, possibly to aid his nearly faultless ability to retain pictorial images. With as many as four hundred individual prints, and with illustrated books that he owned bringing the total up to more than a thousand pictures, all this in a personal collection, ready for daily study, he had an unusual resource for his work. He read ancient and modern poetry and the fiction of his contemporaries and understood exactly how literary artists dealt with the visual arts. To a degree probably unusual for his time and situation, he read art criticism, art history, and studies of the works of individual artists and schools of art. He knew the writings of Giorgio Vasari, Roger de Piles, Charles Du Fresnoy, John Dryden, Johann Winckelmann, Joshua Reynolds, Luigi Lanzi, Madame de Stal, John Ruskin, and James Jackson Jarves. He read Frank Cundalls book about the painters of Holland, John William Molletts studies (Sir David Wilkie, Rembrandt, Meissonier, and The Painters of Barbizon), Cosmo Monkhouses Turner, and Owen John Dulleas Claude. His marginalia in the books he owned, even those primarily about other topics, indicate his alertness to any remarks about the arts. He carefully marked Goethes account of his Italian journey, with its many references to encounters with art. His copy of Madame de Stals Corinne, purchased in 1849 (and no longer available), must, with its disquisitions upon art, have provided much for him to think about.

In one of his most remarkable descriptions of a work of art, the lost city of Petra, Melville has his speaker, Rolfe, offer a reaction to the sight: One starts. In Esaus waste are blent / Ionian form, Venetian tint (Clarel 2.30.1718). The passage marks the two major functions of literary pictorialism. Art allusion is textural, on a small scale; it embellishes and emblazons, in Venetian tint, a passage of prose or poetry. An example is the Hawaiian savage, whose carving is as close packed in its maziness of design, as the Greek savage, Achilles shield (Moby-Dick 270). On the other hand, Ionian form is achieved by means of ekphrasis, the literary description of a work of visual art, a passage, usually of some length and complexity, that contributes to the structure of the tale or poem. The ekphrasis of Petra, taking a whole canto of the poem, admirably fills such a function by being central to an interpretation of the whole work. It is my hope that a close look at both structural and textural elements in certain of Melvilles writings will give a sense of how his visual imagination expresses itself in ever-more secure and sophisticated literary technique.

In his George Eliot and the Visual Arts, Hugh Witemeyer wisely points out that generalizations about the relations of literary works to such things as schools of art are really not very workable. Quoting Bernard Richards on following the guidelines of what poets and painters actually saw and read, Witemeyer states, as his own guiding principle, the necessity for associating Eliots writings primarily with pictures and pictorial traditions which she knew (6). I agree with Witemeyers conscientious narrowing of the focus of such study and have attempted to do something similar in this discussion of Melvilles debt to art and his contribution to pictorialism.

Studies of Melvilles whole-hearted involvement with the plastic arts have laid the groundwork for our increased comprehension of this complex topic. In Melvilles Reading (1966; 1988) Merton Sealts tabulated the great extent to which Melville depended upon books and magazine articles for his art education. Sealtss reconstruction of the lecture on statuary in Rome (1957) and his careful notes give a good sense of the ways in which Melville studied works of art. Morris Stars dissertation, Melvilles Use of the Visual Arts (1964), helped to lay out the range of the subject and suggest modes of study. Hennig Cohens perceptive notes to his edition of Melvilles Selected Poems (1964) called attention to the frequent use of the visual arts in the poetry. Some individual essays during the 1970s and 1980s noted the persistence of Melvilles sense of the plastic arts, and Stuart M. Franks Herman Melvilles Picture Gallery (1986) exhibited many of the illustrations that must have served Melville in the writing of Moby-Dick.

Two books in particular have contributed much to my study. With Savage Eye: Melville and the Visual Arts