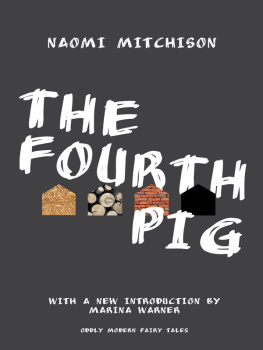

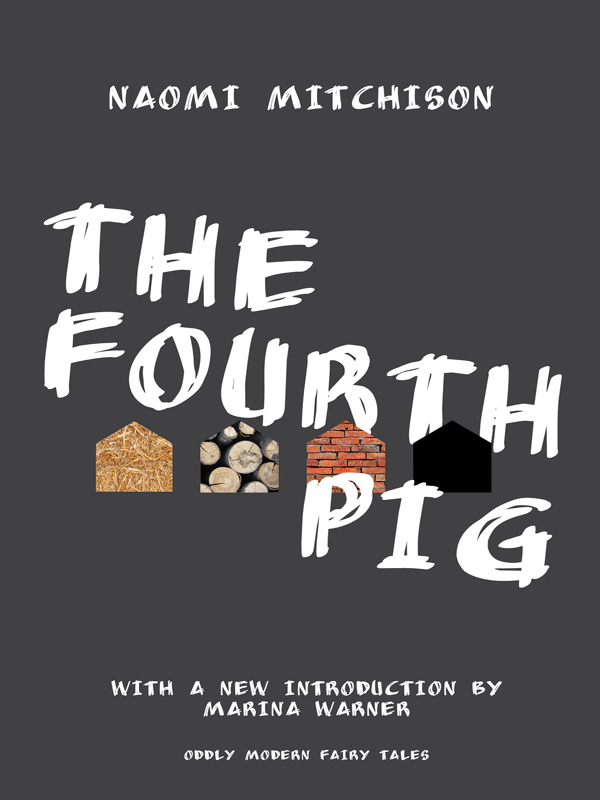

THE FOURTH PIG

ODDLY MODERN FAIRY TALES

JACK ZIPES, SERIES EDITOR

Oddly Modern Fairy Tales is a series dedicated to publishing unusual literary fairy tales produced mainly during the first half of the twentieth century. International in scope, the series includes new translations, surprising and unexpected tales by well-known writers and artists, and uncanny stories by gifted yet neglected authors. Postmodern before their time, the tales in Oddly Modern Fairy Tales transformed the genre and still strike a chord.

Naomi Mitchison, The Fourth Pig

Kurt Schwitters, Lucky Hans and Other Merz Fairy Tales

Bla Balzs, The Cloak of Dreams: Chinese Fairy Tales

Peter Davies, editor, The Fairies Return: Or, New Tales for Old

THE FOURTH PIG

NAOMI MITCHISON

WITH A NEW INTRODUCTION BY

MARINA WARNER

Princeton University Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2014 Estate of Naomi Mitchison

Introduction copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by arrangement with Kennedy & Boyd

(www.kennedyandboyd.co.uk)

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work

should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

First published in 1936 by Constable and Company Ltd., London,

and the Macmillan Company of Canada, Ltd., Toronto

press.princeton.edu

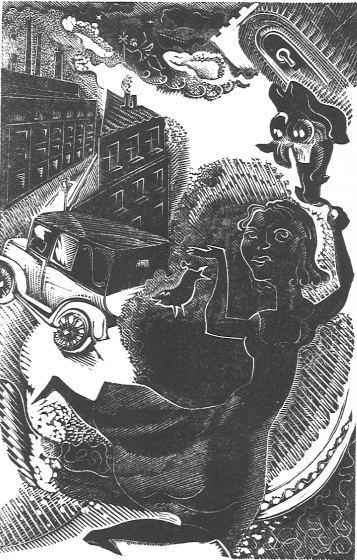

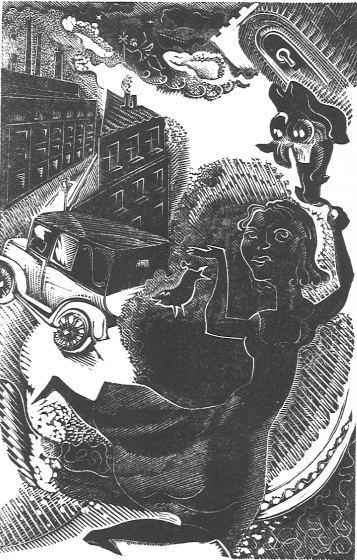

The frontispiece and title page were designed by Gertrude Hermes

Jacket Art: Bunches of hay An Nguyen; piles of firewood GoodMood

Photo; brick wall antpkr. All images courtesy Shutterstock.

Jacket design by Jessica Massabrook.

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 9780-691158952

Library of Congress Control Number 2013954729

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Cronos Pro & Adobe Jenson Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

INTRODUCTION

I have said very little here about my writing. It is my job and I think I do it well. In some ways my writing is old-fashioned, but I doubt if that matters much. I know I can handle words, the way other people handle colours or computers or horses.

Naomi Mitchison, aged 90

Reviewing a book by the poet Stevie Smith in 1937, the year after The Fourth Pig was published, Naomi Mitchison opened with a characteristic cri de coeur: Because I myself care passionately about politics, because I am part of that we which I am willing to break my heart over, and can no longer properly feel myself an I, because that seems to me to be the right thing for me to do and be, I see no reason why everyone has got to. Stevie Smith can still be an I. And thats good. She is thinking about her contemporarys enviable singularity of experience and voice: Such people dont have to be we; they can be I, proudly and bouncingly as The passage is revealing in many ways: Naomi Mitchisons style is colloquial, vigorous, and unsentimental; it drew praise from E. M. Forster, for example, for the directness with which she brought distant, exotic characters to life before the readers eyes. Furthermore, the review reveals her generosity of spirit: where some critics might inflict a wound, she embraces a potential rival or adversary, insisting on others democratic right to difference. But above all, her sense that she belonged to a group or a class, rather than enjoyed the free play of subjectivity like the visionary Blake, or the inspired eccentric Stevie Smith, reflects an anguished split deep down in Naomi Mitchisons consciousness.

She was right to recognise this division in herself, between public duty and private vision, between communal feeling and personal passion, between elite learning and popular lore. She was torn all her life between her intellectual, feminist ambitions and her wealthy, patrician upbringing and way of lifethe incalculable advantages of her background, as Vera Brittain put it. Nou Mitchison, ne Haldane, was a woman from the Big House, as she put it in the title of a story for children.

Her double consciousness created further tensions that pull her writing this way and that, between solemnity and frivolity, mandarin and demotic language, between playful ingenuousness and harsh defiance of convention. She was born in 1897; her Naomis girlhood was enmeshed in dynastic kinship systems; her grandparents were wealthy landowners in Scotland, with huge, chilly castles, salmon brooks, deer-stalking, while her parents, by contrast, were Liberal and progressive and brilliant. Her father, John S. Haldane, was a distinguished medical biologist at Oxford and, deeply concerned for working men and women, led pioneering work on lung disease at the beginning of the century, diagnosing the miasmas that killed in the mines, factories, and mills of industrialised Britain. He also helped invent the first gas masks for protection in World War I. His concerns shaped his two children more profoundly than his wifes sense of class and etiquette.

Naomis older brother, J.B.S. (Jack) Haldane, made an even greater mark, as a geneticist and biologist. He was a colossal personality, and his transgressiveness, independent-mindedness, and sheer cleverness set a bar for Naomi she was always longing to leap. He was a free, even wayward spiritsacked from Cambridge for adultery with a colleagues wife (he married her), he became a Communist, and later, an Indian nationalist, renouncing his British citizenship. When they were children, theyd been allies and equals and sparring partners; they played charades and dressed up, putting on plays they wrote themselves; they experimented together on scientific questions, cross-breeding coloured guinea pigs, and cutting up a caterpillarthis last was intended to be a rug for the dolls house, but it shrivelled (a lesson in life and death).

After this enchanted though stormy alliance, Jack was sent away to school (Eton), whereas Naomi had to stay at home. Before then she had been a rare girl attending the boys Dragon School in Oxford. Jacks going away, the arrival of a governess for all-important lessons in decorum, the new ban on climbing trees, all gave Naomi a bitter taste of gender injustices. The title of Small Talk (1973), a marvelous, witty, and tender memoir about her childhood, catches the stifling restrictions she suffered, and she never overcame her ferocious jealousy of her brother. Consequently Jack dominates his little sisters fiction in various little-disguised heroic personae. But her imagination also stamped out in her stories one spirited daredevil young woman after anotherwild girls, strong-limbed and tousled, who break rules, act vigorously, and reject mincing and simpering. This is what I found in her books when I was young, when I too was furious that being female still prevented me from being as free as a male.

Naomi, the faery child, had intense dreams and kept open the connection to childlike wonder and terror. I met a brown hare, she remembers, and we went off and kept house (marriage as I saw it) inside a corn stook with six oat sheaves propped around us. She did not know then, she continued, that the hare is closely associated with the moon and the goddess, as well as with witchcraft. As I remember it, I was married young to the hare.

Next page