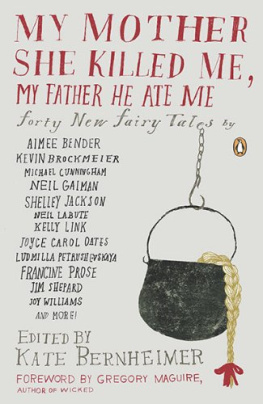

My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me: Forty New Fairy Tales

INTRODUCTION by Kate Bernheimer

DESPITE ITS HEFT, THIS COLLECTION IS A TINY HALL OF MIRRORS IN the worlds giant house of fairy tales. Fairy tales comprise thousands of stories written by thousands of writers over hundreds of years. A volume published in the mid-twentieth century that purported to catalog every type of folktale in existence had more than twenty-five hundred entries; since then, countless new stories have joyously entered the world via new translations, folkloric research, and artists working in a multitude of forms.

Readers love fairy tales. Even the most virulent critics of fairy tales cant look away. With their false brides, severed limbs, and talking donkeys, they are hypnotic. All great novels are great fairy tales, wrote Nabokov. I would argue that all great narratives are great fairy tales. whatever their shape (novel, novella, short story, poem).

About fifteen years ago, when I began to acquaint myself with the scholarship surrounding fairy tales in order to think about my own body of work within the tradition, I became aware of a fairy-tale resurgence. Soon after that I edited my first collection, Mirror, Mirror on the Wall essays by women writers about the influence of fairy tales on their work. I also embarked on a trilogy of novels about the influence of fairy-tale books on three sisters. And now I am thrilled to see an even more widespread infatuation with wonder stories in popular book series like J. K. Rowlings Harry Potter, Philip Pullmans His Dark Materials, and Gregory Maguires Oz books; in stand-alone novels such as Donna Tartts The Little Friend and A. S. Byatts The Childrens Book; on television, whether obviously, as in any number of vampire shows, or quietly, as in the shape and surreal motifs of Six Feet Under; and in film, where Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and Alice in Wonderland are but two examples. Magic is in the air.

I was weaned on fairy tales. My grandfather, who may or may not have worked for Disney (nobody is certain) and who may or may not have worked with a Bostonian piano thief (we think he did), screened fairy-tale films in his basement for me and my siblings when we were young. The flying beds, cackling witches, and warbling birds shaped my being. In combination with terrifying Holocaust footage screened at my temple and stories of burning bushes, singing spring turtles, and parting seas the consolation of magical stories was directly imprinted on me. I was shy, happiest inside books; their open world beckoned and took me in.

Over the past seven years, as founder and editor of Fairy Tale Review, I have seen the passionate interest fairy tales hold for the thousands of writers who submit to every issue. I founded the journal out of a sense that literary works based on fairy tales, like the lonely heroes of fairy tales themselves, lacked homes. I was immediately flooded with very good manuscripts. Many hopeful correspondents are well-known authors whose magical works have been turned down by older literary publications; others are true believers and have devoted their lives to folklore in unusual ways creating fairy-tale newspapers, selling homemade fairy-tale wares, producing freely distributed fairy-tale comics; still others are grandfathers, mothers, teachers, biologists, or students who as new writers feel comfortable trying on the fairy-tale form. I am touched by every submission; each shines with love for fairy tales.

When I lecture on fairy tales, whether at museums or grade schools, I am always moved by the audiences deep pleasure in learning about fairy-tale techniques. Fairy tales defy the status quo: a reader will easily recognize a version of Little Red Riding Hood that contains no cape, no woods, and no wolf. See Matthew Brights amazing film Freeway in which a young Reese Witherspoon plays an abused kid who runs away from home and youll understand; its a direct homage to The Story of Grandmother, interpreted in this collection by the inimitable Kellie Wells. Fairy tales have a fairy-tale likeness.

Ive had the privilege of introducing many students to the fairy tales strange history, so carefully studied by such scholars as Maria Tatar and Jack Zipes, who teach us that originally fairy tales were not directed toward children, though they were overheard by youngsters around the hearth, and that they function in an almost totemic way for both young and old. My love of fairy tales drives all of my writing, whether a novel, a short story, or a book for children. I have the honor of making my day-to-day work the celebration of fairy tales. All of this the journal editorship, the teaching of craft, the casual conversations, the life of a writer reflects back to me that fairy tales are simply essential, and I want to share that with you.

But odd things, too, led me to gather this volume.

I have a sense that a proliferation of magical stories, especially fairy tales, is correlated to a growing awareness of human separation from the wild and natural world. In fairy tales, the human and animal worlds are equal and mutually dependent. The violence, suffering, and beauty are shared. Those drawn to fairy tales, perhaps, wish for a world that might live forever after. My work as a preservationist of fairy tales is entwined with all kinds of extinction.

I was also inspired to collect this volume based on my experience in the community of writers and readers. A few years ago I presented a short manifesto about fairy tales to a large audience of creative writing professors and students. I was on a panel dedicated to nonrealist literature. I made an argument that fairy tales were at risk they had been misunderstood, appropriated without proper homage by the realists and fabulists alike. Only at a writers conference could this sort of statement provoke a gasp. (Yes, say what you will.) I am always that person in the room telling everyone, genuinely, that I love it all realism, high modernism, surrealism, minimalism. I like stories. But apparently my defense of fairy tales, which I consider so poignantly inclusive, marginalized, and vast, was seen as outlandish. (Note: there are a lot of realists and nonrealists in this collection. Some of my best friends are realists and nonrealists, too.) My statement, intended to be inspiring, to gather support for this humble, inventive, and communal tradition, created vibration, metallic and sharp. I realized the full weight of the fact that celebrating fairy tales in the center of a talk about serious literature to a roomful of writers was controversial. This surprised me but it also emboldened me to put together this volume.

Indeed it was at that meeting that this book was born. I realized how essential this volume was, for it would gather all kinds of literary writers in the service of fairy tales. I realized then that while people may know and love or love to hate these stories, they really are not aware of the many ways they pervade contemporary literature.

As merely one example, the National Book Foundation, which administers the National Book Awards, states that retellings of folk-tales, myths, and fairy-tales are not eligible for their awards. Imagine guidelines that state, Retellings of slavery, incest, and genocide are not eligible. Fairy tales contain all of those themes, and yet the implication is that something about fairy tales is simply. not literary. Perhaps the snobbery has something to do with their association with children and women. Or it could be that, lacking any single author, they discomfit a culture enchanted with the myth of the heroic artist. Or perhaps their tropes are so familiar that they are easily misunderstood as clich. Possibly their collapsed world of real and unreal unsettles those who rely on that binary to give life some semblance of order.