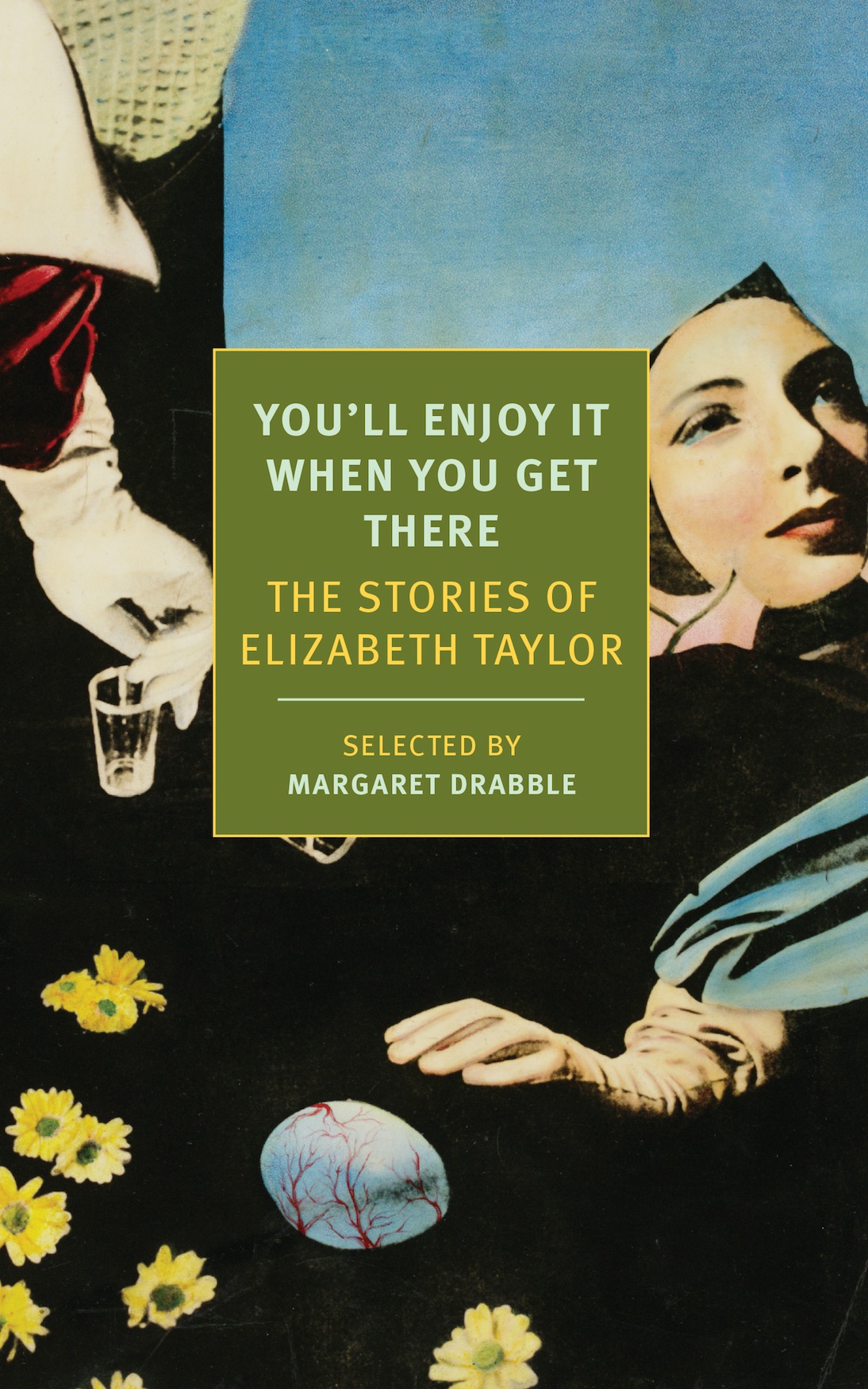

ELIZABETH TAYLOR (19121975) was born into a middle-class family in Berkshire, England. She held a variety of positions, including librarian and governess, before marrying a businessman in 1936. Nine years later, her first novel, At Mrs. Lippincotes, appeared. She would go on to publish eleven more novels, including Angel and A Game of Hide and Seek (both available as NYRB Classics), four collections of short stories (many of which originally appeared in The New Yorker, Harpers, and other magazines), and a childrens book, Mossy Trotter, while living with her husband and two children in Buckingham-shire. Long championed by Ivy Compton-Burnett, Barbara Pym, Robert Liddell, Kingsley Amis, and Elizabeth Jane Howard, Taylors novels and stories have been the basis for a number of films, including Mrs. Palfrey at the Claremont (2005), starring Joan Plowright, and Franois Ozons Angel (2007).

MARGARET DRABBLE is the author of eighteen novels, including The Needles Eye, The Peppered Moth, The Seven Sisters, The Sea Lady, and most recently, The Pure Gold Baby. Among her works of nonfiction are biographies of Arnold Bennett and Angus Wilson. She has edited the fifth and sixth editions of the Oxford Companion to World Literature and was made a Dame of the British Empire in 2008.

HESTER LILLY

M URIELS first sensation was one of derisive relief. The nameHester Lillyhad suggested to her a goitrous, pre-Raphaelite frailty. That, allied with youth, can in its touchingness mean danger to any wife, demanding protectiveness and chivalry, those least combatable adversaries, against which admiration simply is nothing. For if she is to fling herself on his compassion, she had thought, at that age, and orphaned, then any remonstrance from me will seem doubly callous.

As soon as she saw the girl an injudicious confidence stilled her doubts. Her husbands letters from and to this young cousin seemed now fairly guiltless and untormenting; avuncular, but not in a threatening way.

Hester, in clothes which astonished by their improvisationthe wedding of out-grown school uniform with the adult, gloomy wardrobe of her dead motherlooked jaunty, defiant and absurd. Every garment was grown out of or not grown into.

I will take her under my wing, Muriel promised herself. The idea of an unformed personality to be moulded and high-lighted invigorated her, and the desire to tamper withas in those fashion magazines in which ugly duckling is so disastrously changed to swan before our wistful eyesmade her impulsive and welcoming. She came quickly across the hall and laid her cheek against the girls, murmuring affectionately. Deception enveloped them.

Robert was not deceived. He understood his wifes relief, and, understanding that, could realise the wary distress she must for some time have suffered. Now she was in command again and her misgivings were gone. He also sensed that if, at this point, she was ceasing to suspect him, perhaps his own guilt was only just beginning. He hated the transparency of Muriels sudden relaxation and forbearance. Until now she had contested his decision to bring Hester into their home, incredulous that she could not have her own way. She had laid about him with every weapon she could findcool scorn, sweet reasonableness, little girl tears.

You are making a bugbear of her, he had said.

You have made her that, to me. For months, all these letters going to and fro, sometimes three a week from her. And I always excluded.

She had tried not to watch him reading them, had poured out more coffee, re-examined her own letters. He opened Hesters last of all and as if he would rather have read them privately. Then he would fold them and slip them back inside the envelope, to protect them from her eyes. All round his plate, on the floor, were other screwed up envelopes which had contained his less secret letters. Onceto break a silencehe had lied, said, Hester sends love to you. In fact, Hester had never written or spoken Muriels name. They had not been family letters, to be passed from one to the other, not cousinly letters, with banal enquiries and remembrances. The envelopes had been stuffed with adolescent despair, cries of true loneliness, the letters were repellent with egotism and affected bitterness, appealing with naivety. Hester had been making, in this year since her fathers death, a great hollow nest in preparation for love, and Robert had watched her going round and round it, brooding over it, covering it. Now it was ready and was empty.

Unknowingly, but with so many phrases in her letters, she had acquainted him with this preparation, which must be hidden from her mother and from Muriel. She had not imagined the letters being read by anyone but Robert, and he would not betray her.

You are old enough to be her father, Muriel had once said; but those scornful, recriminating, wifes words never sear and wither as they are meant to. They presented him instead with his first surprised elation. After that he looked forward to the letters and was disappointed on mornings when there was none.

If there were any guilty love, he was the only guilty one. Hester proceeded in innocence; wrote the letters blindly as if to herself or as in a diary and loved only men in books, or older women. She felt melancholy yearnings in cinemas and, at the time of leaving home, had become obsessed by a young pianist who played tea-time music in a caf.

Now, at last, at the end of her journey, she felt terror, and as the first ingratiating smile faded from her face she looked sulky and wary. Following Muriel upstairs and followed by Robert carrying some of her luggage, she was overcome by the reality of the house, which she had imagined wrong. It was her first visit, and she had from Roberts letters constructed a completely different setting. Stairs led up from the side of the hall instead of from the end facing the door. I must finish this letter and go up to bed, Robert had sometimes written. So he had gone up these stairs, she thought in bewilderment as she climbed them now.

The building might not have been a school. The mullioned windows had views of shaved lawnsdesertedand cedar trees.

I thought there would be goal-posts everywhere, she said, stopping at a landing window.

In summer-time? Muriel asked in a voice of sweet amusement.

They turned into a corridor and Robert showed Hester from another window the scene she had imagined. Below a terrace, a cinder-track encircled a cricket field where boys were playing. A white-painted pavilion and sight-screens completed the setting. The drowsy afternoon quiet was broken abruptly by a bell ringing, and at once voices were raised all over the building and doors were slammed.

When Muriel had left herwith many kind reminders and assurancesHester was glad to be still for a moment and let the school sounds become familiar. She was pleased to hear them; for it was because of the school that she had come. She was not to share Muriels life, whatever that may be, but Roberts. The social-family existence the three of them must lead would have appalled her, if she had not known that after most meal-times, however tricky, she and Robert would leave Muriel. They would go to his study, where she would provemust proveher efficiency, had indeed knelt down for nights to pray that her shorthand would keep up with his dictation.

From the secretarial school where, aged eighteen, she had vaguely gone, she had often played truant. She had sat in the public gardens, rather than face those fifteen-year-olds with their sharp ways, their suspicion of her, that she might, from reasons of age or education, think herself their superior. Her aloofness had been humble and painful, which they were not to know.

![T.L. Taylor [T.L. Taylor] - Watch Me Play](/uploads/posts/book/131712/thumbs/t-l-taylor-t-l-taylor-watch-me-play.jpg)