Zhuangzi

TRANSLATIONS FROM THE ASIAN CLASSICS

Translations from the Asian Classics

EDITORIAL BOARD

Wm. Theodore de Bary, Chair

Paul Anderer

Irene Bloom

Donald Keene

George A. Saliba

Haruo Shirane

David D.W. Wang

Burton Watson

Zhuangzi

Zhuangzi BASIC WRITINGS

Translated by

BURTON WATSON

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York

Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2003 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-52133-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zhuangzi.

[Na hua jing. English Selections]

Zhuangzi : basic writings / translated by Burton

Watson.

p. cm.(Translations from the Asian classics)

Includes index.

ISBN 0231129599 (pbk.)

I. Watson, Burton, 1925 II. Title. III. Series.

BL1900.C46 E5 2003

299.51482dc21 2002034766

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Contents

In 815 the Chinese poet-official Bai Juyi, having offended the authorities by his outspoken criticisms of government policy, was dismissed from his position at court and shunted off to an insignificant post in the Yangzi region far to the south, a virtual sentence of exile. Not long after arriving at his new post, he wrote the following poem entitled Reading Zhuangzi:

Leaving homeland, parted from kin, banished to a strange place,

I wonder my heart feels so little anguish and pain.

Consulting Zhuangzi, I find where I belong:

surely my home is there in Not-Even-Anything land.

As a result of his sudden reversal of fortune, Bai was abruptly separated from almost everything that defined life for a Chinese gentleman of his class: native region, extended family (his wife was allowed to accompany him into exile), public office. In terms of traditional values, he had in effect been stripped of his identity, his reason for being. One would expect him to be totally crushed by such a turn of events. And yet, to his own surprise, as he declares in the poem, he finds himself relatively untroubled by grief or depression. His reading of Zhuangzi has enabled him to view himself and his age from a loftier plane, one that transcends conventional concepts of time and place, duty and social position. Zhuangzis writings have freed him, as they have so many readers down through the centuries, from his narrower identity as a native of a particular locale, a player in a particular role in life, and made him a dweller in all time and place, in the land that Zhuangzi calls Not-Even-Anything because it is in fact everything and everywhere.

It is no doubt this loftiness and liberality of outlook that has made the work known as the Zhuangzi such an enduring favorite with readers in China and the other countries within the Chinese cultural sphere in the two thousand and more years since its appearance. And it is this same breadth of vision, along with the brilliant and imaginative language in which it is couched, that allows the work to soar over the barriers of translation and win new readers in other countries and cultural spheres. The Zhuangzis engaging anecdotes, with their potent wit and humor to propel them, have by now traveled far beyond the borders of Asia, and there are probably few places in the world where the tale of Zhuangzis butterfly dream is not known.

Of the four philosophers that I translated in my Basic Writings series, the other three, Mozi, Xunzi, and Han Feizi, though they deal with political and moral questions of universal significance, strike one as inseparably linked to ancient China, the age and society that gave them birth. But Zhuangzi, because of his inspired and unconventional language and the visionary ideas he expounds, seems to float free of his environment and to be in the end addressing all persons and ages. He was, I must admit, the most difficult to translate, but at the same time the most rewarding, because I felt that I was dealing here with a text of timeless import.

In terms of readership as well, I am happy to note, Zhuangzi appears to be in an orbit of his own. While the other philosophers in the Basic Writings series have steady but quite modest annual sales, presumably mainly to students who are taking courses in Asian thought or culture, Zhuangzi seems to have been able to reach out to a much broader and more varied audience. It is to be hoped that in this newly revised edition, he will continue to expand his circle of readers, further testimony to the lasting appeal and importance of his writings.

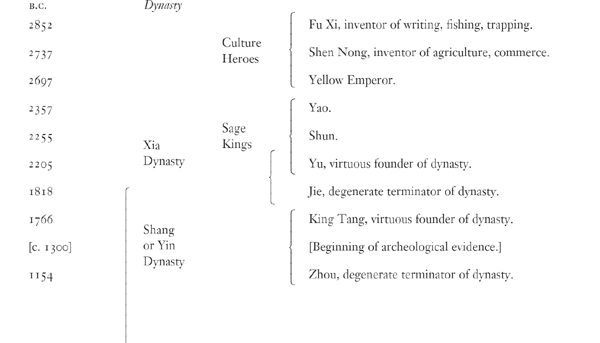

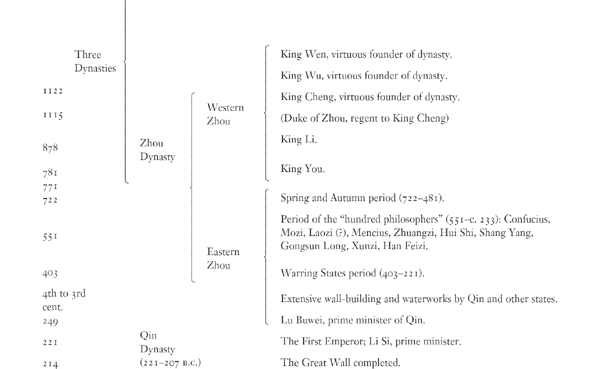

(Dates and entries before 841 B.C. are traditional)

All we know about the identity of Zhuangzi, or Master Zhuang, are the few facts recorded in the brief notice given him in the Shiji or Records of the Historian (ch. 63) by Sima Qian (145?89? B.C. ). According to this account, his personal name was Zhou, he was a native of a place called Meng, and he once served as an official in the lacquer garden in Meng. Sima Qian adds that he lived at the same time as King Hui (370319 B.C. ) of Liang and King Xuan (319301 B.C. ) of Qi, which would make him a contemporary of Mencius, and that he wrote a work in 100,000 words or more which was mostly in the nature of fable. A certain number of anecdotes concerning Zhuangzi appear in the book that bears his name, though it is difficult, in view of the deliberate fantasy that characterizes the book as a whole, to regard these as reliable biography.

Scholars disagree as to whether lacquer garden is the name of a specific location, or simply means lacquer groves in general, and the location of Meng is uncertain, though it was probably in present-day Henan, south of the Yellow River. If this last supposition is correct, it means that Zhuang Zhou was a native of the state of Song, a fact which may have important implications.

When the Zhou people of western China conquered and replaced the Shang or Yin dynasty around the eleventh century B.C. , they enfeoffed the descendants of the Shang kings as rulers of the region of Song in eastern Henan, in order that they might carry on the sacrifices to their illustrious ancestors. Though Song was never an important state, it managed to maintain its existence throughout the long centuries of the Zhou dynasty until 286 B.C. , when it was overthrown by three of its neighbors and its territory divided up among them. It is natural to suppose that not only the ruling house, but many of the citizens of Song as well, were descended from the Shang people, and that they preserved to some extent the rites, customs, and ways of thought that had been characteristic of Shang culture. The Book of Odes, it may be noted, contains five Hymns of Shang which deal with the legends of the Shang royal family and which scholars agree were either composed or handed down by the rulers of the state of Song. Song led a precarious existence, constantly invaded or threatened by more powerful neighbors, and in later centuries its weakness was greatly aggravated by incessant internal strife, the ruling house of Song possessing a history unrivaled for its bloodiness even in an age of disorder. Its inhabitants, as descendants of the conquered Shang people, were undoubtedly despised and oppressed by the more powerful states which belonged to the lineage of the Zhou conquerors, and the man of Song appears in the literature of late Zhou times as a stock figure of the ignorant simpleton.