ALFRED HAYES (19111985) was born into a Jewish family in Whitechapel, London, though his father, a barber, trained violinist, and sometime bookie, moved the family to New York when Hayes was three. After attending City College, Hayes worked as a reporter for the New York American and Daily Mirror and began to publish poetry, including Joe Hill, about the legendary labor organizer, which was later set to music by the composer Earl Robinson and recorded by Joan Baez. During World War II Hayes was assigned to a special services unit in Italy; after the war he stayed on in Rome, where he contributed to the story development and scripts of several classic Italian neorealist films, including Roberto Rossellinis Pais (1946) and Vittorio De Sicas Bicycle Thieves (1948), and gathered material for two popular novels, All Thy Conquests (1946) and The Girl on the Via Flaminia (1949), the latter the basis for the 1953 film Act of Love, starring Kirk Douglas. In the late 1940s Hayes went to work in Hollywood, writing screenplays for Clash by Night, A Hatful of Rain, The Left Hand of God, Joy in the Morning, and Fritz Langs Human Desire, as well as scripts for television. Hayes was the author of seven novels, a collection of stories, and three volumes of poetry. In addition to My Face for the World to See, NYRB Classics publishes In Love.

DAVID THOMSON is film critic at The New Republic and has been a frequent contributor to Sight & Sound, Film Comment, The Guardian, and The Independent. He is the author of A Biographical Dictionary of Film and, most recently, The Big Screen: The Story of the Movies. He has also written several novels, including Suspects and Silver Light.

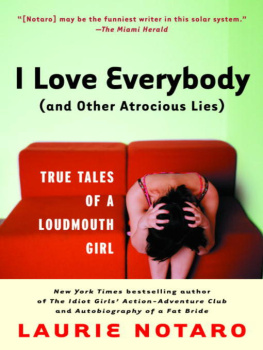

MY FACE FOR THE

WORLD TO SEE

ALFRED HAYES

Introduction by

DAVID THOMSON

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 1958 by Alfred Hayes; copyright renewed 1986 by Marietta Hayes and Alan Hayes

Introduction copyright 2013 by David Thomson

All rights reserved.

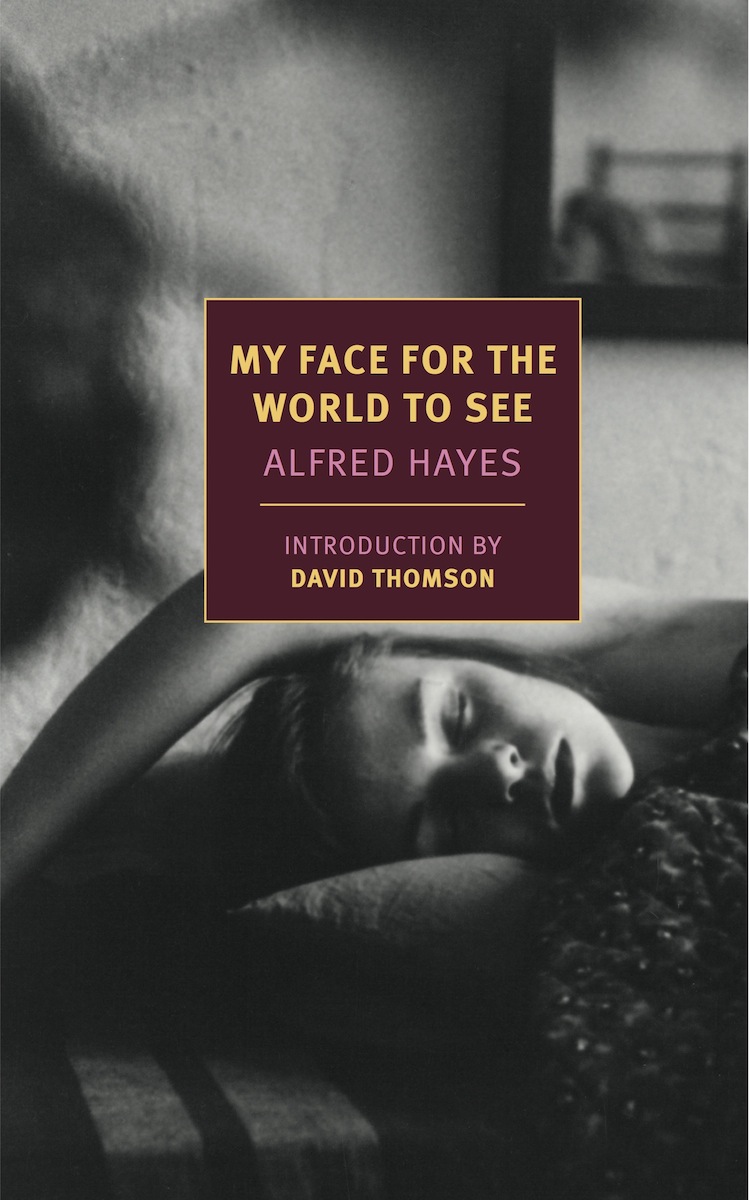

Cover image: Saul Leiter, Sleep, c. 1955; Saul Leiter; courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

Cover design: Katy Homans

The Library of Congress has cataloged the earlier printing as follows:

Hayes, Alfred, 19111985.

My face for the world to see / by Alfred Hayes ; introduction by David Thomson.

pages ; cm. (New York review books classics)

ISBN 978-1-59017-667-2 (alk. paper)

I. Title.

PS3515.A9367M9 2013

813'.52dc23

2013008975

eISBN 978-1-59017-694-8

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

T HE MAN is at a beach party in Los Angeles, bored by the event and inclined to look at the oceanThere it was, exactly as advertised, he notes, and then a girl, a pretty girl, comes into view. She wears shorts, a Basque shirt, and a yachting cap, and shes carrying a drink. Her legs glimmered a little in the darkness. As she walks into the sea she seems to be in control. But then a wave floors herShe really went under. He goes in to save her, and that night he manages to be the hero even if his pants are ruined. But theres no salvation in the long run, not for her, not for him. In the course of this terse novel, they neither of them acquire or deserve names.

My Face for the World to See was published in 1958, when Alfred Hayes was forty-seven. Born in London, he had left for the United States as a young child and in 1943 was drafted into the American army, and thats how he had been to Italy where he contributed to the scripts of two famous neorealist movies, Roberto Rossellinis Pais, and Vittorio De Sicas Bicycle Thieves. Then he came back to America and wrote his most successful novel, The Girl on the Via Flaminia, published in 1949. For the next ten years, he was kept busy in Hollywood and, with or without credit, worked on a series of interesting picturesTeresa, for Fred Zinnemann; The Lusty Men, by Nicholas Ray; two films for Fritz Lang, Clash by Night and Human Desire; Island in the Sun, an interracial love story that was big at the box office; A Hatful of Rain, an early study of drug addiction, taken from a play by Michael V. Gazzo; The Barbarian and the Geisha, a John Huston picture, starring John Wayne, about Japan in the nineteenth century.

Hayes was comfortable, though thats not the same as pleased. The man in this novel seems a success, too, but he has no self-respect. When the girl asks him if hes writing at one of the studios now, I said I wasnt, really; I was writhing. This girl has been saved from suicide, but the man has his own settled, established disquiet. He is earning a salary somewhat in excess of what they paid an aged vice- president of a respectable bank. But he is unconvinced by such credentials. After all, Hayes was a poet (he wrote Joe Hill), a novelist of clenched power and dismay, and a man fairly certain that the advertised benefitsthe ocean, the movie happiness, marriagedidnt work out.

The man has left his wife and a cold marriage in New York, but the forlorn girl walking into the Pacific hardly surprises him. At this very moment, he says,

the town was full of people lying in bed thinking with an intense, an inexhaustible, an almost raging passion of becoming famous if they werent already famous, and even more famous if they were; or of becoming wealthy if they werent already wealthy, or wealthier if they were.... There were times when the intensity with which they wanted these things impressed me. There was even, at times, a certain legitimacy to their desires. But it seemed to me, or at least it had seemed to me in the few years I had been coming and going from this town, there was something finally ludicrous, finally unimpressive about even the people who had all the things so coveted by all the people who did not have them.

Hayes is the dry poet of the things we think about while lying in bed, when sleep refuses to carry us off. As this novel begins, the man seems in the superior position. He is older than the girl; he has a career; he watches her and the ocean from an upper balcony. Then he asks if shed like to have dinnershe is prettyand soon enough, the words will slip out of him, the unfelt, I love you, rather as he might have someone say that in a movie script. Isnt that the kind of thing people are supposed to say? Moreover, the girl is a failure. Hoping to act, she does only auditions, and the tenuousness of her personality suggests the ordeals she may have faced at those occasions. She has been ill. She has a shrink who is holding off billing her until she makes it. When the lover takes her to a bullfight in Tijuana (a magnificent, remorseless scene) she is emotionally devastated.

One night as they are in bed together in his house, he watches her asleep. She is moaning, grinding her teeth. She cries out, No, no. He decides their affair is a mistake.

I thought: she shouldnt sleep with anybody if she doesnt wish them to know her secrets. It was something more than her nakedness: more than the exhaustion after love. She was in the bed as she would be in a ditch or a field. She slept like someone who could not go any further and had already come too far. I stretched myself out beside her, a stranger, a spy, sharing the warmth of the bed. Morning seemed immeasurably far.