It's a pleasure to acknowledge the scientists who have helped shape my understanding of Earth's recent climates and the scholars who have guided my path as I learned how geologists originally advanced our understanding of climate. It's also a pleasure to thank those remarkably patient friends and family members who supported me on a personal level as I labored for far too long over the manuscript of this book.

Long ago the late professor Sheldon Judson of Princeton University's Geology Department taught me the basic outline of how radically different were parts of the Pleistocene Epoch from what we experience on Earth today. He explained the geologic evidence for the episodic cold-warm-cold-warm pattern of Earth's recent climates presented in the . I took him to the finest gravel quarry in the whole west, where we stealthily trespassed on a Sunday to see the natural record of the back flooding from Glacial Lake Missoula as well as earlier flooding from Glacial Lake Bonneville. Sheldon doffed his hat at the beauty of what lay before us, clear evidence of the truly violent effects of geologically recent variations in climate.

After Sheldon's death, his widow Pamela Judson-Rhodes helped me in my fieldwork one summer, navigating our journeys on a profusion of topographic maps and helping me collect sediment samples shaped by fluctuations in climate. It's a pleasure to publicly thank Pamela for her direct help that summer and for earlier lending me a considerable part of Sheldon's time during his retirement.

Lincoln and Sarah Hollister, also of Princeton, have supported me as an author for many years now, sending warm words across three thousand miles as I sat through various snowy and bitter Northwest winters at the desk of my basement study. They also read an early draft of this book and sent me valuable comments about it.

Washington State University has given me several colleagues whom it's a pleasure to publicly thank with respect to this book. Kent Keller, a geohydrologist, helped me when I was on WSU's teaching faculty, and he has shared with me some of his ideas and concerns about climate and greenhouse gases in more recent years. Talking with Kent about natural and anthropogenic climate change and related questions of energy policy has always been a pleasure, and I've learned a lot from our discussions. Gary Webster, David Gaylord, and Mike Pope, all of WSU's Geology Department, visited me in the field when I studied the late Pleistocene and Holocene sediments of northeastern Washington State while on sabbatical. That interval was the period of my life I was able to devote simply to exploring natural evidence of stupendous, natural climate change and the side effects entailed by such changes. Later, when I was teaching an interdisciplinary science course with Lisa Carloye, I reviewed my earlier field experiences to use them in freshmen-level lectures. Working with Lisa was itself a pleasure, and it was out of our common efforts to talk to nonscience majors about climate change that the idea for this book was formed. After the writing was well underway, George Mount helped me by critically reading the manuscript of what became of this book; I deeply appreciate both his technical corrections and how quickly he read what I gave him.

A colleague from outside technical life at WSU has also been of great assistance to me. At some point in the 1990s I was fortunate to fall into a series of conversation with Jerry Gough of WSU's History Department. Those talks led me to sit in on the classes Jerry taught for years on the history of science. The history of geology had been an interest of mine since my days as a teaching assistant for Stephen J. Gould at Harvard University. Jerry quickly took up my education where I had left it in New England, and over many years now he has been an excellent teacher. With respect to this book, Jerry outdid himself, reading and editing both an early draft organized in one framework and a later and quite different draft. I don't think I would have persevered to the end of this project without Jerry's constant and cheerful encouragement.

The librarians at WSU's Owen Science and Engineering Library were essential to the preparation of this volume. The circulation librarians fetched obscure volumes for me via interlibrary loan. They also calmly coped with my ability to misplace the books I check out. Then there are the true heroines of the story, the reference librarians of Owen. Time and time again, they rescued me when I was about to give up hope of learning a bit more about a nineteenth-century geologist or tracking down something that was alleged to be in the Congressional Record but failed to appear there. My joy at finding pieces of good material for this book was shared by a revolving set of reference librarians who manned the help desk at Owen, and I appreciate their assistance more than I can say. When I am finally called home by the Lord, I firmly believe it will be to an enormous library, one staffed by dedicated librarians like we have here on Earth.

The of this book, which discusses in part the worldwide plague of unwanted coal fires around the world, was enriched by my correspondence with geologist Glenn B. Stracher of East Georgia College. Glenn is an authority on such fires, which burn out of control like forest fires but are scarcely reported in the news. My concern about the fires and their effects is surpassed only by my gratitude to those specialists who have done the careful work of showing just how detrimental such fires are to both local environments and the global atmosphere.

Turning to my more personal debts, it's a pleasure to note that several friends conspired to help me with this project. Dean Ritchie read and responded to the outline I first put together to organize my thinking. Karl and Mary Anne Boehmke generously read the entire first draft of the manuscript, as did Sharon Rogers. My loyal friends Mary Elisabeth Rivetti, Julia Pomerenk, and Susan Bentjen put up with my tedious reports about how the project was proceeding over the several years it unfolded. My friends, I suspect, may have suffered even more than I did during some of the difficult chapters, but they remained steadfast to the belief that one day we would all be released from this effort.

My colleagues at Prometheus Books have been helpful, prompt, and always professional. Brian McMahon deserves special mention for patiently copyediting the manuscript, finding many ways to improve the text.

Finally, but perhaps most importantly, Russell Galen in New York took me on as an author and pushed me to improve what I produced. We had to turn several corners together to reach a manuscript we hope might be useful to the reader. I sincerely thank Russ for his time, his criticisms, and above all his implicit encouragement.

Writing anything at all about climate is complex, and it is almost bound to be controversial in some quarters. It's therefore worth explicitly noting that although many colleagues and friends have helped shape my thinking about Earth's climate, I alone am responsible for the shortcomings of this volume.

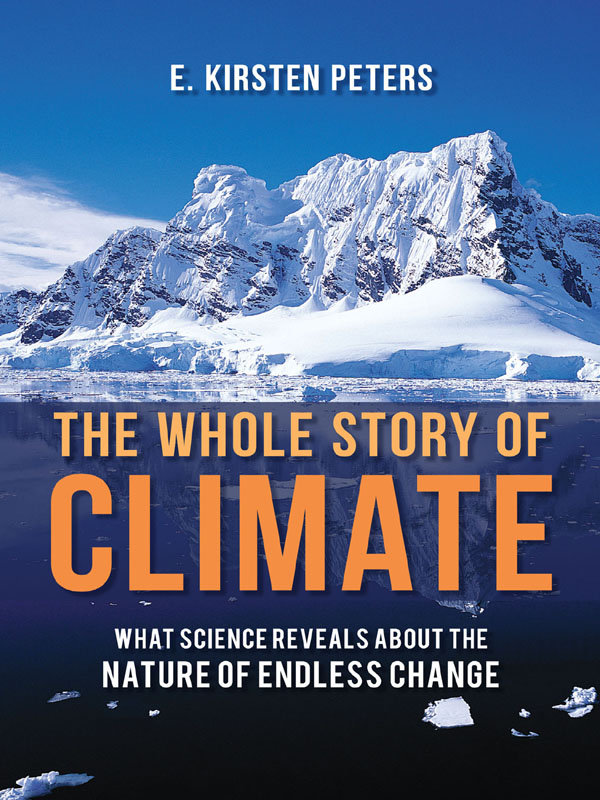

Dr. E. Kirsten Peters majored in geology at Princeton University and earned her doctorate in geology from Harvard. She has published technical abstracts and articles in her field of expertise as well as essays about science, religion, and the challenges of teaching college students to write. She has taught geology and interdisciplinary science classes at Washington State University, where she is a faculty member. She is the author of two textbooks in geological science and has been a freelance editor for college-level materials in oceanography, environmental science, and geology. In recent years she has created a nationally syndicated newspaper column called The Rock Doc that explains topics in science and technology to a general audience.

Next page