Dambudzo Marechera - The House of Hunger

Here you can read online Dambudzo Marechera - The House of Hunger full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2002, publisher: Penguin Books Ltd, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The House of Hunger

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin Books Ltd

- Genre:

- Year:2002

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The House of Hunger: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The House of Hunger" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The House of Hunger — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The House of Hunger" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Charles William Dambudzo Marechera was born in June 1952 in Vengere, the township of Rusape, in the east of the then Rhodesia. He was the third of nine children in a family which became destitute once his father was killed in a road accident in 1966. He gained entry to one of the first secondary schools to be opened to blacks the Anglican St Augustines Mission School at Penhalonga. In 197273 he was inscribed as an English major at the University of Rhodesia. From 1974 he studied further on a scholarship at New College, Oxford, from which he was sent down in March 1976 to live out his exile in Britain in a succession of squats for another six years. He contributed to several publications, including The New African and the London Sunday Times, hammering out the first draft of The House of Hunger on his portable typewriter in a matter of three weeks.

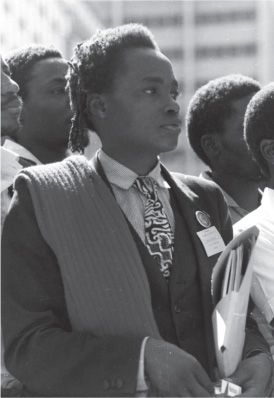

First Street reading during the Harare Book Fair, 1983

Notoriously on his return to independent Zimbabwe in February 1982 with a Channel Four crew intent on filming him, he was confronted with the news that his second novel, Black Sunlight (1980), had been banned. When Lewis Nkosi viewed the film at the 1983 Zimbabwe International Book Fair, he called it a marvellous, scandalous document, recording the scars left by colonial society on one of the most original talents yet to emerge in African Literature. Marechera became noted as a tramp, writing in public on park benches, as recounted in the journal of his return to his native land included in Mindblast, published in 1984. He lived to see his The House of Hunger taken as the mouthpiece of his generation and then of the new internal exiles post-independence. Later he could afford a bedsitter in the centre of Harare, where in January 1987 he was diagnosed with pneumonia as a complication of AIDS. In May that year, in an interview with Kirsten Holst Petersen, he noted: I lead a very solitary life, and so most of the time I am simply reading, in here or outside. He died in August that year, aged thirty-five.

Reading at the College of Music in Harare, 1984

The House of Hunger first appeared in the Heinemann African Writers Series in December 1978, with an edition soon published by Pantheon in New York. A translation of the whole sequence into German followed after his appearance at the Horizonte Festival in West Berlin in 1979, with others into Dutch and French, with Protista going into Norwegian and Burning in the Rain into Portuguese. For the original edition he was awarded the Guardian Fiction Prize in 1979, jointly with Neil Jordan (250 each). Reviewing it for The Guardian, one of the competition judges, Angela Carter, remarked: It is indeed rare to find a writer for whom imaginative fiction is such a passionate and intimate process of engagement with the world. The first edition included the title novella, with nine additional sketches and short stories, a few of which were intended to be read as interrelated with the main text. Here some of the makeweights have been omitted in favour of later pieces written to complete The House of Hunger cluster. They are The Sound of Snapping Wires (first published in West Africa on 7 March 1983), with the three last essays, all unpublished at the time of his death. The prefatory An Interview with Himself of 1983 is also an addition here.

Kole Omotoso in West Africa (14 September 1987):

Dambudzo Marecheras life provided the material for his art. His existence, to those intent on their business of living, seemed dedicated to dying. On 18 August he finally completed the process that began with his birth.

David Caute in The Southern African Review of Books (Winter 198788):

The writer Dambudzo Marechera died in Harare at the age of thirty-five. A brilliant light, flashing fitfully in recent years, is extinguished. He once wrote: Its the ruin not the original which moves men; our Zimbabwe ruins must have looked really shit and hideous when they were brand-new.

Dieter Riemenschneider in Research in African Literatures (Fall 1989):

Marecheras first-person narrator in a story like The Slow Sound of His Feet is unable to restore a life that is both meaningful and worth living. He paints a harrowing picture of the individual suffering of a person who bears much resemblance to the author himself.

Dan Wylie in English in Africa (October 1991):

Marechera is the misfit. His The House of Hunger is a characteristically turbid, angst-ridden, dadaesque story virtually unparalleled in African fiction, by a profoundly dislocated writer living in a shattered, repulsive environment of mindless violence, raw sex, filth and madness.

Lisa Combrinck in Work in Progress (August 1993):

Above all, Marechera believed that the task of the writer in a changing society was to be honest, true to him- or herself and never hypocritical. Young South and other Africans who read Marechera will probably, like their Zimbabwean counterparts, embrace his works as a militant young lion who bravely criticised the government in the post-uhuru period.

Jean-Philippe Wade in Alternation (1995):

The House of Hunger is one of the most important texts to emerge from Southern Africa in recent decades. It should be on every school and university syllabus, because these powerful stories challenge just about every complacently hegemonic view of what African Literature is.

Wole Soyinka, nominating Scrapiron Blues as his book of the year (1996):

A profound, even if exaggeratedly self-aware writer, an instinctive nomad and bohemian in temperament, Marechera was a writer in constant quest for his real self.

A K Thembeka in Laduma (2004):

He was a black who read all their books, and let them know it in the relentless stream of quotes that littered his prose. The literati rewarded him, not for his achievements, but for his struggle.

Kgafela oa Magogodi in Outspoken (2004):

my song grows from the ground

where Marechera rose to write

Stephen Gray (2009):

The central text in this revised The House of Hunger collection is well enough established by now as the unforgettable, virtuoso accomplishment of African writing in English of the 1970s. Indeed, with its overlapping scenes of horror and of humour, it rattled the staid and timorous establishment like a refreshing outburst from a mighty imagination, setting itself impressively free. Supported here as it is now by various satellite pieces to complete the cluster, it reads all the more finely.

I find the question oblique, not to the point. It assumes a writer has to be influenced by other writers, has to be influenced by what he reads. This may be so. In my own case I have been influenced to a point of desperation by the dogged though brutalised humanity of those among whom I grew up. Their actual lives, the way they flinched yet did not flinch from the blows dealt out to us day by day in the ghettos which were then called locations.

They ranged from the few owners of grocery stores right through primary school teachers, priests, deranged leaders of fringe/esoteric religions, housewives, nannies, road-diggers, factory workers, shop assistants, caddies, builders, pickpockets, psychos, pimps, demoralised widows, professional con-men, whores, hungry but earnest schoolboys, hungry but soon to be pregnant schoolgirls and, of course, informers, the BSAP, the police reservists, the TMB ghetto police, the District Commissioner and his asserted pompous assistants and clerks, the haughty and rather banal Asian shopkeepers, the white schoolgirls in their exclusive schools, the white schoolboys whod beat us too when we foraged among the dustbins of the white suburbs, the drowned bodies that occasionally turned up at Lesapi Dam, the madman who was thought harmless until a mutilated body was discovered in the grass east of the ghetto, the mothers of nine or more children and the dignified despair of the few missionaries who once or twice turned up to see under what conditions I was actually living. This is the they. The seething cesspit in which I grew, in which all these I am talking about went about making something of their lives. These are the ones who influenced me through their pain, betrayals, hurts, joys.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The House of Hunger»

Look at similar books to The House of Hunger. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The House of Hunger and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.