DAVID LYNCH SWERVES

DAVID LYNCH SWERVES

Uncertainty from Lost Highway to Inland Empire

MARTHA P. NOCHIMSON

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS

AUSTIN

Copyright 2013 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2013

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

PERMISSIONS

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

http://utpress.utexas.edu/about/book-permissions

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nochimson, Martha.

David Lynch swerves : uncertainty from Lost Highway to Inland Empire / by Martha P. Nochimson. First edition.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Includes filmography.

ISBN 978-0-292-72295-8 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Lynch, David, 1946 Criticism and interpretation. I. Title.

PN1998.3.L96N53 2013

791.4302'3092dc2012040910

doi: 10.7560/722958

ISBN: 978-0-292-74460-8 (e-book)

ISBN: 978-0-292-74889-7 (individual e-book)

CONTENTS

.

.

.

.

.

.

PREFACE

CRITIC ON FIRE

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack, a crack in everything

Thats how the light gets in.

LEONARD COHEN, ANTHEM

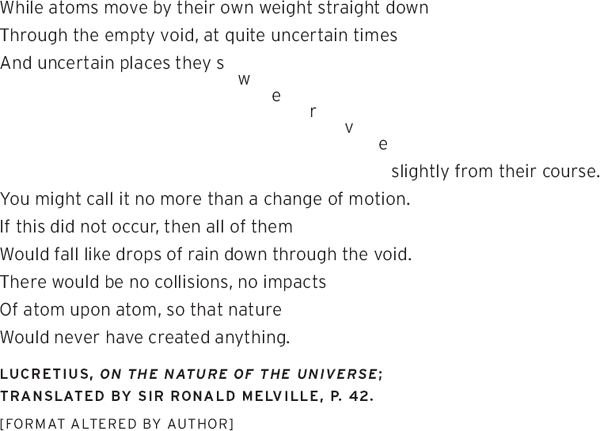

In The Passion of David Lynch (1997), aided by the ideas of Carl Jung, I followed Lynch up to the boundaries of ordinary cultural discourse as he looked beyond them to much larger realities. Tracing a path from Lynchs early student work to Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, I argued that to understand the Lynchian vision we must open ourselves up to Lynchs unique depiction of an organic reality that lies beyond the limits we, as a part of a culture that obsessively draws lines, have imposed on our lives. True enough, but not quite the whole story. Although, at the end of that book, I commented briefly about Lost Highway as if it could be understood within the framework I had outlined, I eventually found myself faced with a need to recognize that that film and Lynchs subsequent cinema have dramatically altered the circumstances of Lynch criticism. Hence the need for David Lynch Swerves.

With my first book about Lynch, I became one of the pioneers of a major redirection of Lynch criticism. and I had to let go of old assumptions (once again) and follow him.

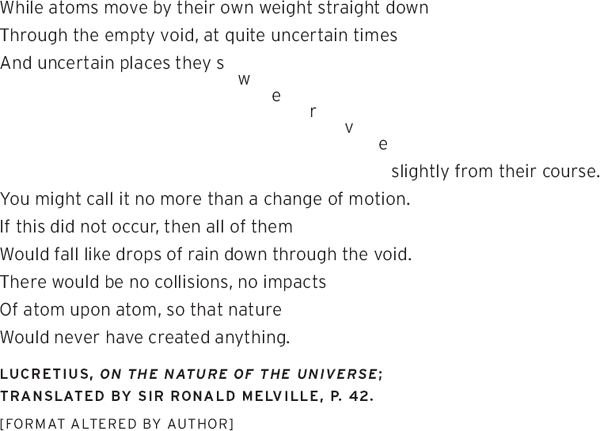

I stand by what I said in my first book, as far as it went. At the time I wrote it, given what Lynch had then revealed to me about his sense of a universal unity linking us all, Jungs ideas seemed to help explain the intriguing growth and development of Lynchs visionary protagonists in his work up to Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. But Jung didnt have a word to say about Lynchs shifting emphasis in Lost Highway and in his subsequent films, in which many very disorienting images of the physical world took center stage. Then I remembered that for twenty years, Lynch had mentioned physics to me whenever we talked, and I began to investigate his cinema, especially from Lost Highway to the present, with quantum mechanics and relativity in mind. My more recent, post-1997, increasingly revealing conversations with Lynch have confirmed my new directionand given me a new frame of reference.

The climactic moment came on March 18, 2010, when Lynch and I spent three hours talking in his compound in the Hollywood Hills. In a long, frank, unguarded conversation, Lynch told me about his vision of the physical world as an uncertain place that masks important universal realities, enunciated for him not by Carl Jung, but by the Holy Vedas of the Hindu religion. At the same time that Lynch told me that he is fascinated by physics, he emphasized that he knows very little about the nuts of bolts of the scientific method used by physicists. (I barely graduated from high school.) He was more comfortable vividly describing the universal center of consciousness evoked by the Hindu holy text. His wholehearted affirmation of his Vedic map of the universe made it clear why he re mains optimistic about life even though he finds the physical landscape on which we live to be unstable.

David Lynch in his hillside retreat, the site of our March 18, 2010, interview.

As Lynch spoke, he burned away my Jungian ideas. Nevertheless, much that he said also corresponded remarkably with the scientific constructs relating to the disorienting, shifting plane of objects and bodies that emerged from experiments conducted by modern physicists in the 1920s, theories that since then have identified even more intense mysteries about the physical plane of life. Lynchs passionate words about the Vedas, and the specter of modern physics that haunted our discussion, generated sparks when they struck against each other in my mind. The tinder burst into flame, casting a new, more illuminating light on Lynchs filmsincluding that mysterious night on the lawn.

In the scene on the lawn outside in amazing ways to the cosmos.

In the scene on the lawn and many others like it, as we shall see in the chapters to come, Lynch provocatively offers his audience unique images of the linkage of inner and outer that must be acknowledged in its full complexity if we are to see the films that Lynch made, and not the much less interesting films that his critics have invented. A full and rich reading of Lynch must not only take into account the many levels of human interiority, but also Lynchs images that reference the many possibilities offered by the multiple levels of the external world of matter. The latter have, to date, gone virtually unremarked. The character of the external world in Lynchs filmic universes has all but eluded criticism so far. Its time for a change.

It is also time for a change about the way we explore the entirety of Lynchs work. It is now clear that with Lost Highway, Lynchs filmmaking altered significantly. We all sensed that there was something about Lost Highway quite different from anything Lynch had done previously, but no one was ready to integrate that intuition into a coherent approach to all of Lynchs cinema and television. Now that Lynch has made

Next page