New York Review Books Classics Songs of Kabir Kabir, the North Indian devotional or

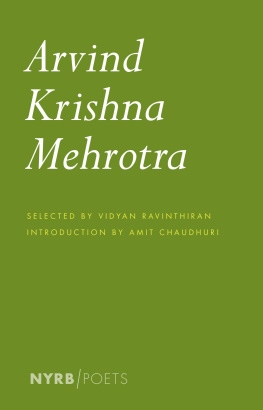

bhakti poet, was born in Benares (now Varanasi) and lived in the fifteenth century. Next to nothing is known of his life, though many legends surround him. He is said to have been a weaver, and in his resolutely undogmatic and often riddling work he debunks both Hinduism and Islam. The songs of this extraordinary poet, philosopher, and satirist, who believed in a personal god, have been sung and recited by millions throughout North India for half a millennium. Arvind Krishna Mehrotra is the author of four books of poetry, the editor of

The Oxford India Anthology of Twelve Modern Indian Poets and

Collected Poems in English by Arun Kolatkar, and the translator of

The Absent Traveller: Prakrit Love Poetry. A volume of his essays,

Partial Recall: Essays on Literature and Literary History will be published in 2011.

He is a professor of English at the University of Allahabad and lives in Allahabad and Dehra Dun. Wendy Doniger [OFlaherty] graduated from Radcliffe College and received her Ph.D. from Harvard University and her D.Phil. from Oxford University. She is the Mircea Eliade Distinguished Service Professor of the History of Religions at the University of Chicago and the author of many books, most recently The Bedtrick: Tales of Sex and Masquerade, The Woman Who Pretended to Be Who She Was, and The Hindus: An Alternative History.

Contents

This is a New York Review Book Published by The New York Review of Books 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014 www.nyrb.com Copyright 2011 by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra Preface 2011 by Wendy Doniger All rights reserved.

Cover image: Dayanita Singh, from Dream Villa Cover design: Katy Homans Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kabir, 15th cent. [Poems. English. Selections] Songs of Kabir / by Kabir ; translation and introduction by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra ; preface by Wendy Doniger. p. (New York Review Books classics) 1. (New York Review Books classics) 1.

Kabir, 15th cent.Translations into English. 2. Hindi poetryTo 1500Translations into English. I. Mehrotra, Arvind Krishna, 1947 II. Title.

PK2095.K3A2 2011 891.4312dc22 eISBN 978-1-59017-399-2

v1.0 For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

Introduction

I Very little is known about Kabir outside what can be culled from his poems or from hagiographies and legends.

According to the latter, Kabir lived for 120 years, from 1398 to 1518. Modern scholars, however, take a more realistic view, but are divided over whether he was active in the first or the second half of the fifteenth century. Kabir (whose name is a Quranic title of Allah meaning great) was born in Benares in a Muslim family recently converted to Islam. The family belonged to the Julahaor weavercaste, and it is safe to assume that the chief reason for the conversion was its low status in the Hindu social system. There are occasional references to the family profession in Kabirs poems. In one poem in particular, addressed to his anxious mother, he talks of dismantling his loom because, he says, he cannot both thread the shuttle and hold the thread of that supreme reality, which he called Rama or Hari, in his hand.

Someone who is the lord of three worlds, he says, is not going to let them starve. Kabir was married and had a son and daughter; perhaps two sons and two daughters. Kabirs hagiographers, who have been around since c. 1600, approve neither of his marriage (they would prefer him to be celibate) nor, indeed, of his lowly origin, and over the years various accounts of his life were concocted to provide him with, among other things, a better pedigree. The legends, however, ended up highlighting precisely what they were meant to conceal. In one of them, a Brahmin widow once accompanied her father on a pilgrimage to the shrine of a famous ascetic.

To reward her devotion, the ascetic prayed that she be blessed with a son. The prayer was answered but there was one problemBrahmin widows are not supposed to get pregnantand she had to abandon the infant. The wife of a weaver, who was passing that way, discovered the child and took him home. The child was Kabir. Other legends presented Kabir as a die-hard rebel. It is said that Kabir chose to spend his last days not in Benares, the holiest of holy Hindu places, a city that promises salvation to all who die there and where he had lived all his life, but in an obscure town called Maghar, which from ancient times has been associated first with Buddhists, and later with Muslims and the lower castes.

He who dies in Maghar is reborn as an ass, Kabir says in one poem, expressing a popular belief. The move to Maghar has a clear message: the place of ones death is of no consequence; salvation can be found anywhere. It was Kabirs last act of defiance. In his distaste of humbug, Kabir can remind you of Diogenes. He was born in a Muslim household, but poured scorn on their qazis, or lawgivers, at every opportunity. He had Hindu followers, but reserved his sharpest barbs for pundits.

In the end, he slipped through the fingers of both Islam and Hinduism. A famous story about Kabir tells how, following his death, both Hindu and Muslim mobs laid claim to his body. The Hindus were adamant to cremate and the Muslims to bury him, but when they removed the shroud they found instead of the cadaver a heap of flowers. The two communities peacefully divided the flowers and performed Kabirs last rites, each according to its custom. But the legends do not end here. When Kabir arrived in heaven, he was received by the four great Hindu gods, Brahma, Siva, Vishnu, and Indra.

Delighted to see him, they asked him to make himself at home. Indra even got up from his throne and offered it to Kabir. Vishnu said: My heaven is yours. Live here forever. This is my wish. And so it was that the crackpot weaver of Benares who had derided Hindu religious practices all his life was on the road to being deified himself.

Kabir is part of the larger devotional turn known as the bhakti movement. Described as a great many-sided shif t... in Hindu culture and sensibility, Bhakti began in South India, in the country of the Tamils, in the sixth century CE but over time acquired a pan-Indian character. It moved to Karnataka in the tenth and Maharashtra in the twelfth centuries, but it was in North India, between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, where it found perhaps its fullest expression. Bhakti favored the informal over the formal, the spontaneous over the prescribed, and the vernacular over Sanskrit. In a well-known verse, Kabir compared Sanskrit, the language of the gods and the preserve of Brahmins, to kupa jal, the stagnant water of a well, and bhasha (vernacular, in which the bhakti poets sang) to the running water of a stream.

With bhakti, it has been said, a new kind of person or persona [came] into fashio n... : a person who flouts proprieties, refuses the education of a poet, insists that anyone can be a poetfor it is the Lord who sings through one. Lying beside you, Im waiting to be kissed. But your face is turned And youre fast asleep. KG 19 Of all bhakti poets, of whom there were many (they seem to appear in droves, in interacting groups of three or four in these early times said A . K.

Ramanujan, referring to the Tamil poets of the sixth and seventh centuries) and who wrote in different languages (Tamil, Kannada, Telugu, Marathi, Gujarati, Kashmiri, Assamese, Oriya, Avadhi), Kabir is the most outspoken. He is ever ready to engage the reader, to harangue him, toif it comes to thatwrestle him to the ground and shout in his ear: Friend, You had one life, And you blew it.