Published in RAINLIGHT by

Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd. 2012

7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110002

Sales Centres:

Allahabad Bengaluru Chennai

Hyderabad Jaipur Kathmandu

Kolkata Mumbai

Copyright Gulzar and Nasreen Munni Kabir 2012

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted,

or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,

without the prior permission of the publisher.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The moral right of the authors has been asserted.

Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro 11.5/16.3

Printed at Replika Press Pvt. Ltd., Haryana

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not,

by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated,

without the publishers prior consent, in any form of binding or cover

other than that in which it is published.

Conversations

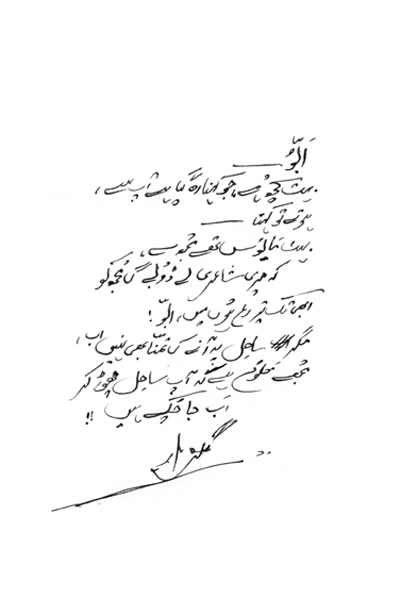

Father

There is much to say that is left unsaid

If you were here I would speak

You were so despondent on my account

Fearing my poetry would drown me some day

I am still afloat, father

No longer have I the desire to return to shore

The shore you left so many years ago.

Gulzar

A picture of grace

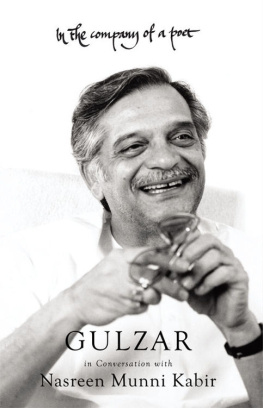

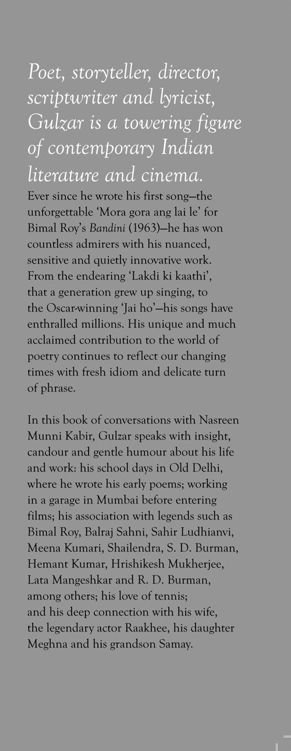

Nearly all stories have back-stories and the story of how I came to meet gulzar Saab dates to 1986 when I was directing a forty-nine-part TV series called Movie Mahal for Channel 4 in the UK. Khalid Mohammed, who was working at The Times of India in those days as their film critic, helped us by interviewing some of the subjects in the series. Since Khalid knew many people in the hindi film industry, he requested gulzar Saab to let us film him discussing the great lyricists of the past.

Gulzar Saab agreed and asked us to come to Boskyana, his house in Pali hill. We were curious about the Russian sounding name of the housewhich turned out to be a discreet and unpretentious one-story white bungalowand later discovered it had been named after Raakheejis and his only daughter, Meghna, whom gulzar Saab affectionately calls Bosky.

When we arrived on the day of filming, we were directed inside the house through a passage where a row of shoes and sandals were neatly lined. The stonewalled sitting room with its neutral colours was almost austere in mood and appearance. Extending into a corner of the room we could see gulzar Saabs office. Books of all sizes and shapes were stacked on the shelves. His writing table and every other surface in the room heaved under the weight of more books.

Perfectly on time, gulzar Saab came in dressed in a starched white cotton kurta-pyjama and was introduced to us. He was a picture of grace with his fine features, soft-spoken manner and natural reserve. He waited patiently while we set up the shot and when the camera was running he came alive speaking animatedly about Sahir Ludhianvi, D. N. Modak and Shailendra. He had many insightful things to say about these wonderful poets. We left delighted with the interview and honoured to have met him.

We met once again in 1990 when we interviewed him for a Channel 4 tV documentary I was making on Lata Mangeshkar, and as ever, he came up with unusual and perceptive observations on her singing. In the following years, I saw gulzar Saab sometimes at a film event or a private screening where I noticed that he would leave before anyone elsei later learned that he does not enjoy late nights, habitually getting up at dawn to go and play tennis.

Preposterous as this might sound, the trigger for this book came to me in a dream I had sometime in 2010 in which the great Sahir Ludhianvi and Shailendra bid me to tell gulzar Saab that we should jointly write something on their work. Perhaps the dream was not as outlandish as it may seem, as the reason for our initial meeting involved these very poets. I felt I should at least call gulzar Saab from London and tell him about the dream no matter how overly dramatic the whole story might seem to him.

Before that morning, I never had the occasion to call him and was lucky to have his number at all. A few months earlier when coincidentally I had met him in London, I asked whether his phone numbersthe ones I had from way backwere the same, he wittily said, Wohi hain. Bachpan se (They are the very same, since childhood).

His manager, Mr Kutty, picked up the phone and asked my name and told me to wait. Somehow I expected he would come back to say gulzar Saab was busy or out for the day. But surprisingly, a few minutes later, he came on the line. We exchanged a few pleasantries and then plucking up the courage I told him about the dream. He said very little but as we were talking I sensed it was unlikely we would write about the past poets at that point in time, so I took the opportunity to ask if I could write a book on him. He listened attentively and in his usual elegant manner said: Call me when youre next in India.

When I returned to Mumbai at the end of 2010, gulzar Saab agreed to the idea of a book. We were keen, as far as possible, to avoid going over the same ground as the existing publications on him, including his daughter Meghna gulzars biography Because he is and Saibal Chatterjees Echoes And Eloquences: The Life And Cinema Of Gulzar. So we decided to talk about his childhood and largely focus on his work as a poet, screenwriter and lyricist. I also believed that even if we were to revisit events that were already known, gulzar Saab would shed new light on them from the perspective of who he is today.

Soon after our initial discussions, I returned to London and we started conversing on Skype. Between May and november 2011 we had over twenty-five Skype sessions, each lasting an hour and sometimes two hours. Our conversations in hindustani and English were recorded and later transcribed. As many of the events recalled in the conversations relate to the period prior to the renaming of Bombay to Mumbai, Calcutta to Kolkata and Madras to Chennai, I have used the original city names for consistency.

The brilliant thing about chatting on Skype is the lightness of the encounter. If other things needed more urgent attention, either of us could sign off without appearing rude or rushed. I also had a hunch that Skyping suited him because he seemed to me someone who enjoyed intense discussions but not necessarily ones that would drag on eternally. Most importantly, using Skype gave gulzar Saab greater flexibility in choosing the time when he was in the mood for conversation. It was particularly delightful to see how pleased he was that, at the age of seventy-seven, he knew how to use Skype at all. He told me it was A. R. Rahman who had downloaded the software onto his MacBook air so that they could discuss the songs they were working on while Rahman was in his Chennai studio and gulzar Saab in Mumbai.