Asia Perspectives: History, Society, and Culture

A series of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University

Carol Gluck, Editor

Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery in the Japanese Military During World War II,

by Yoshimi Yoshiaki, trans. Suzanne OBrien

The World Turned Upside Down: Medieval Japanese Society,

by Pierre Franois Souyri, trans. Kathe Roth

Yoshimasa and the Silver Pavilion: The Creation of the Soul of Japan,

by Donald Keene

Geisha, Harlot, Strangler, Star: The Story of a Woman, Sex, and Moral Values in Modern Japan,

by William Johnston

Lhasa: Streets with Memories,

by Robert Barnett

Frog in the Well: Portraits of Japan by Watanabe Kazan, 17931841,

by Donald Keene

The Modern Murasaki: Writing by Women of Meiji Japan, ed. and trans. Rebecca L. Copeland and Melek Ortabasi

So Lovely a Country Will Never Perish: Wartime Diaries of Japanese Writers,

by Donald Keene

Sayonara Amerika, Sayonara Nippon: A Geopolitical Prehistory of J-Pop,

by Michael K. Bourdaghs

The Winter Sun Shines In: A Life of Masaoka Shiki,

by Donald Keene

Manchu Princess, Japanese Spy: The Story of Kawashima Yoshiko, the Cross-Dressing Spy Who Commanded Her Own Army,

by Phyllis Birnbaum

Imitation and Creativity in Japanese Arts: From Kishida Rysei to Miyazaki Hayao,

by Michael Lucken, trans. Francesca Simkin

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2016 Donald Keene

All rights reserved

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

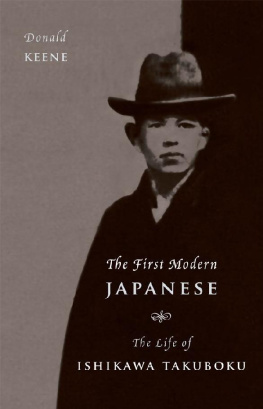

Names: Keene, Donald, author.

Title: The first modern Japanese : the life of Ishikawa Takuboku / Donald Keene.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, 2016. | Series: Asia perspectives: history, society, and culture | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015050684 | ISBN 9780231179720 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231542234 (electronic)

Subjects: LCSH: Ishikawa, Takuboku, 1885 or 18861912. | Poets, Japanese20th centuryBiography.

Classification: LCC PL809.S5 Z72755 2016 | DDC 895.61/4dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015050684

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at cup-ebook@columbia.edu.

COVER IMAGE: Courtesy of Kushiro Public Library and Shinchosha

COVER DESIGN: Chang Jae Lee

To my son Asaz,

who has made the last years of my life the happiest.

Contents

Ishikawa Takuboku (18861912) probably ranks as the most beloved poet of the tanka, a form of poetry composed by innumerable Japanese poets for well over a thousand years. Takubokus tanka stand out less for their beauty than for their individuality; his poems are as surprising today as they were for the first readers. His poems borrowed from no one but managed always to transmit the striking freshness of his thoughts and experiences. Countless poets before him had conveyed in the thirty-one syllables of the tanka such subjects as their perceptions of the changes brought by the seasons or the yearning evoked by the poets love. Takubokus poems seldom touched on these familiar subjects, but he had no intention of destroying the traditions of the tanka with his originality. Instead, he clung to composing his poems in thirty-one syllables, just as other tanka poets had done for two thousand years. And although his essays often urge poets to write in the language of the day, his tanka were always written in the classical Japanese language, even when he described the thoughts of an unmistakably modern man. He rather resembled the French modernist poets who, though determined

The tanka was often beautiful in its imagery and rich in overtones that gave depth, despite the few syllables available to the poet. The language permitted to the poets consisted of a vocabulary that had been established centuries earlier by members of the court in order to maintain elegance of diction, but it limited the subjects. Tanka poets borrowed openly from the poetry of their predecessors; indeed, a poem without reference to the past was not praised. Tanka poets, with no thought of startling, hoped that their variations on familiar themes would be admired for the delicate shifts of older poems or a barely hinted freshness of expression.

The sameness of subjects in the collections of tanka does not apply to the dozen great tanka poets whose poems are unforgettable, even when the subjects are conventional. Although the rise of linked verse in the fourteenth century and of haiku in the seventeenth century gave poets greater freedom of subject and language, they did not eliminate or greatly change tanka. Not until late in the nineteenth century was there a serious call to reject the heritage of the past and create poetry suitable to men of the enlightened Meiji era.

The poems of Masaoka Shiki (18671902), the leader of this new movement, were rarely about the beauty of cherry blossoms or colored autumn leaves and the other lovely but exhausted subjects of poetry. Instead he described in his poems what he had perceived and felt, without worrying whether they might seem unpoetic to readers of traditional poetry. Shikis insistence on writing his poems in modern Japanese resulted in bringing tanka and haiku into the new age and saved both forms from being demolished by the European influences that swept over Japanese poets beginning in the 1880s.

This in itself did not make Shiki a modern poet. He rarely revealed, as a modern poet usually does, his deepest emotions, and he seldom referred to himself in the first person. His best-known tanka sequence requires an understanding of unspoken background poems: Shiki did not reveal that he wrote these poems when he was almost completely paralyzed from an illness that eventually killed him.

Unlike Shiki, Takuboku was a truly modern poet. About sixty years ago, Ksaka Masaaki, a professor of philosophy at Kyoto University, told me he was convinced that Takuboku was the first modern Japanese. This statement lingered in my memory, though at the time I did not know Takubokus work well enough to understand what made him modern.

Although it is difficult to name the qualities that make a poet appear modern, Takubokus poems make their modernity clear without needing further explanation. Here are a few examples:

| ware ni nishi | two friends |

| tomo no futari yo | just like me: |

| hitori wa shini | one dead |

| hitori wa r wo | one, out of jail |

| idete ima yamu | now sick |

Surely no earlier tanka poet ever wrote a poem that included a dead man, a man released from prison, and still another who was sick; and Takuboku resembled all of them:

| arano yuku | like a train |

| kisha no gotoku ni | through the wilderness |

| kono nayami | every so often |

| tokidoki ware no | this torment |

| kokoro wo tru | travels across my mind |