Romaji Diary

AND

Sad Toys

Romaji Diary

AND

Sad Toys

by

Takuboku Ishikawa

Translated by

Sanford Goldstein and Seishi Shinoda

TUTTLE PUBLISHING

Boston Rutland, Vermont Tokyo

This edition published in 2000 by Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd., with editorial offices at 364 Innovation Drive, North Clarendon, VT 05759 U.S.A.

Copyright 1985 by Tuttle Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from Tuttle Publishing.

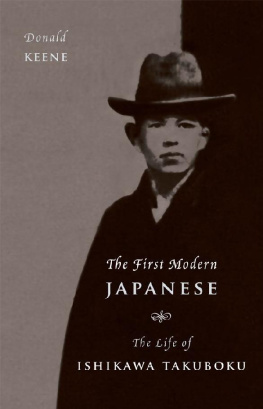

Cover photograph Michael Maslan Historic Photographs/Corbis; artist unknown, "Cherry Blossoms (Spring)," ca. 1890; albumen hand-colored photographic print

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data in Process

ISBN: 978-1-4629-0078-7

Distributed by

| North America | Japan |

| Tuttle Publishing | Tuttle Publishing |

| Distribution Center | Yaekari Building 3rd Floor, 5-4-12 |

| Airport Industrial Park | Osaki Shinagawa-ku, |

| 364 Innovation Drive | Tokyo 141-0032 |

| North Clarendon, VT 05759-9436 | Tel: (03) 5437-0171 |

| Tel: (802) 773-8930 | Tel: (03) 5437-0755 |

| Tel: (800) 526-2778 |

| Fax: (802) 773-6993 |

Asia Pacific

Berkeley Books Pte

61 Tai Seng Avenue, #02-12

Singapore 534167

Tel: (65) 6280-1330

Fax: (65) 6280-6290

inquiries@periplus.com.sg

www.periplus.com

05 04 03 02 01 00 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

Publisher's Note

The publication of this edition of two of Takuboku Ishikawa's finest and most popular works together in translation has proven to be interesting from various standpoints.

Romaji Diary and the collection of tanka, Sad Toys, while different forms of literature, are not as dissimilar as they appear on the surface. Takuboku himself wrote that poetry "must be an exact report, an honest diary, of the changes in a man's emotional life,' and these tanka are indeed as much a diary as a standard prose one. Both works reflect clearly, honestly, and poignantly the emotions and philosophy of a complex individual living in a time of profound change in japan.

The tanka in this volume were first published in a book entitled Sad Toys (Purdue University Press, 1977). Romaji Diary is here presented in full in English for the first time, to the translators' and Publisher's knowledge. The Introduction and the various sets of notes are in large part from the Purdue book, but have been revised and added to where appropriate to fit this new edition.

Acknowledgments

With gratitude to...

Professor Akira Ikari, scholar of Japanese literature at Niigata University, Niigata, Japan, for his numerous helpful suggestions on our manuscript;

Sabur Sait , for his excellent editing of the Iwanami Bunko edition of A Collection of Takuboku's Tanka, first published in 1946 by Iwanami Shoten, Tokyo;

Yukinori Iwaki, scholar-biographer, for his informative studies, The Life of Ishikawa Takuboku, published by T h Shob , Tokyo, 1955, and Ishikawa Takuboku, published by Yoshikawa-Kobunkan, Tokyo, 1965;

Dr. Takeo Kuwabara, for permission to quote from his excellent essay "The Diaries of Takuboku," found in Works of Takuboku, Chikuma Shob , Tokyo, 1968 (originally published in the extra volume of Collected Works of Takuboku, Iwanami Shoten, Tokyo, 1954);

Iwanami Shoten, Tokyo, for permission to photograph the Japanese text of Sad Toys found in Takuboku Kash , 1975, and for the use of the original text in our translation of Romaji Diary, found in volume 16 of Collected Works of Takuboku, 1961 (the suppressed words in this edition were filled in from the Iwanami Bunko edition of 1977); special thanks also to Ry suke Yasue, Chief Editor of Iwanami Shoten.

Introduction

BIOGRAPHY

Poverty, illness, and tankathe traditional thirty-one-syllable Japanese poempermeate many of the twenty-six years of Takuboku Ishikawa's life, and like the contradictory manifestations that moderns are bombarded with, such an unusual triumvirate represents Takuboku's fall and greatness.

Takuboku's father, Ittei Ishikawa, was the fifth son of a peasant in Iwate Prefecture. In mid-nineteenth-century Japan a needy family living in a poor rural community hoped one of its sons would become a priest, the position being a kind of religious protection against the bleak aftermath of life, to say nothing of the immediate security and status such a career offered. Ittei was taught by Taigetsu Katsurahara, who was versed in Chinese classics and skilled in the tea ceremony and who was himself a poet whose tanka, while conventional, were nevertheless well formed. Even Ittei wrote tanka, typical and unoriginal to be sure, but like his teacher's, excellent in structure:

I have given up this world As full of taint, yet there is nowhere to move. __ What shall I do with this aging me? Neither floating nor sinking, I drift, tossed by the waves of years. __ How peaceful the village of Tamayama! The sunshine so soft, Mt. Kohime in haze.

Takuboku's mother, Katsu Kud , was Katsurahara's younger sister, and she herself had been a very bright youngster. The private school she attended had trained her in calligraphy, reading, and some arithmetic.

In 1874, Ittei was appointed temple priest in a village next to Shibutami in Iwate Prefecture. Only twenty-five at the time, he was exceptionally young for the position. Certainly Katsurahara's influence was a major factor in earning Ittei the appointment. It was in this Zen temple that Takuboku was born on February 20, 1886, the third child in a family with two daughters, Sada (ten) and Tora (eight). As Takuboku's parents had separate family registers because Zen priests in those days were not supposed to marry, the child Hajime (Takuboku is a penname) was listed in his mother's family register as a son born out of wedlock to Katsu Kud . It must have been quite surprising to Takuboku's classmates in his second year at lower primary school to find Hajime Kudo had suddenly become Hajime Ishikawa. His father and mother had probably decided it was inconvenient and painful for a schoolboy to have parents with different family names. Bastard children were subject to ridicule and hate.

In 1887, Ittei was transferred to the temple in Shibutami, a village which is on the old highway to Aomori, the northernmost city in Honshu. The former priest had died, but the son who would usually be next in line for the post was too young, so Ittei had been selected. Katsurahara had influenced the incumbent of the head temple to appoint Ittei, while Ittei was himself persuading a group of influential parishioners. The parties concerned disregarded the plight of the bereaved family members, who had to leave the temple without any means of livelihood. Usually members of a village have an interim-incumbent until the temple son is old enough to succeed his dead father, but in this instance no such guarantee was provided. Ittei's hard bargaining caused some villagers to dislike him and to have misgivings about him, so the prize carried with it a residue of antagonism.

After moving to Shibutami, Ittei discovered his chief goal was the reconstruction of the temple, which had been destroyed by fire a decade earlier. By the time he was forty, the task was accomplished, an impressive three-year achievement, but one Ittei was never to equal during the remainder of his own sad life.