Akshay Manwani - Sahir Ludhianvi: The Peoples Poet

Here you can read online Akshay Manwani - Sahir Ludhianvi: The Peoples Poet full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: HarperCollins, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

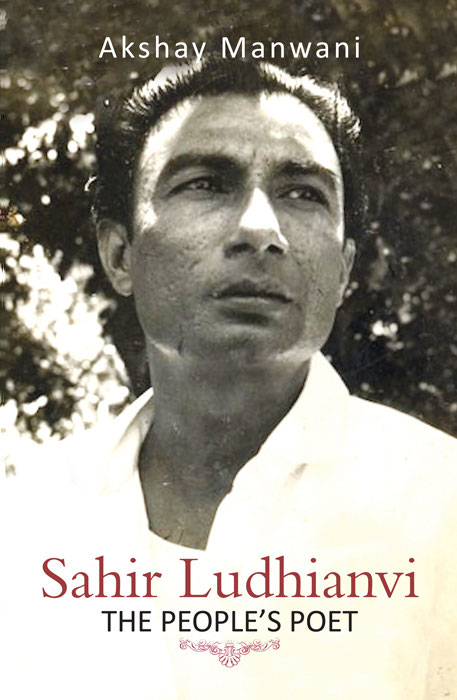

- Book:Sahir Ludhianvi: The Peoples Poet

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Sahir Ludhianvi: The Peoples Poet: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Sahir Ludhianvi: The Peoples Poet" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Sahir Ludhianvi: The Peoples Poet — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Sahir Ludhianvi: The Peoples Poet" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

SAHIR

LUDHIANVI

THE PEOPLE SPOET

Akshay Manwani

HarperCollins Publishers India

To

Mom, Dad, Amma, Achchan,

Naina and Vidya

Main har ek pal ka shaayar hoon, har ek pal meri kahaani hai

Har ek pal meri hasti hai, har ek pal meri jawaani hai

(I am the eternal poet, my story has no end

I am in every moment, my youth never spent)

n his insightful account of the genesis of cricket in India, the historian Ramachandra Guha writes, The social history of Indian cricket suffers from one enormous disadvantage: that we, as a people, have a criminal indifference to the written record.

Guha might well have been speaking for Hindi cinema, for we, as a nation, have mostly ignored documenting the history of perhaps the only obsession other than cricket that cuts across the cultural milieu of India. There is scant literature available on the Hindi film industry, as indeed of the many people who shaped it into its current form. The few biographies that hit bookshelves each year have either the usual suspects, Guru Dutt, Lata Mangeshkar, Amitabh Bachchan, Shah Rukh Khan, as their subjects or are bereft of any substance.

What about the likes of Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Akhtar Ul Imaan, Renu Saluja, V.K. Murthy and scores of other technicians who helped in the evolution of popular Hindi cinema without ever stepping into the limelight? Bunny Reubens and Pran and Jerry Pintos Helen, the latter written without any input from the lady in question, are exceptions, and efforts that must be fted.

Ganesh AnantharamanBollywood Melodies, an outstanding piece of work on the Hindi film song, is another such exception. In many ways, Bollywood Melodies is a catalyst for this book, for it was while reading Anantharamans work that a fundamental truth about the plight of lyricists dawned on me. That of the many times we find ourselves enjoying a melody, there is little or no cognizance of the songwriter. How we never tire of praising Talat Mahmoods or Kishore Kumars vocals. How very frequently we dole out compliments appreciating the genius of Naushad or S.D. Burman. Yet, there is no recollection of the men who penned the words, the men who gave soul to the melody.

Ganesh even offers a plausible explanation for this stepmotherly treatment handed out to lyricists: They [the lyricists] havent usually generated that degree of awe and adulation from film music lovers. Possibly because we are a country with a much stronger oral tradition than a written one, compounded by our higher levels of illiteracy.

Also, a melody isnt constrained by geographical boundaries or distances. Which is why, in a culturally dissimilar nation like ours, where language changes every 500 miles, it was possible for Bombay Ravi to gain popularity in the Kerala film industry, but impossible for Kaifi Azmi to captivate the states Malayalamspeaking population with his Urdu lyrics. A corollary to this characteristic of a melody works to the advantage of composers in another way as well. There are innumerable instances of film compositions being inspired by folk music or having strong regional or Western influences. Yet, it is the craft of the songwriter that gives the song an identity of its own.

Take, for example, the evergreen Ae dil hai mushkil, jeena yahaan from C.I.D. (1956). The tune for this is directly inspired from an American folk ballad Oh my darling, Clementine. The words in the original are those of a bereaved lover who loses his beloved in a drowning accident. In contrast, the song in C.I.D. has an element of joy to it. It is bereft of the lament that characterizes the original and is, instead, a vivid, lyrical description of Bombay. If the song has become Bombays unofficial anthem over the years, it is Majrooh Sultanpuris wonderful play with words, rather than O.P. Nayyars score, that is responsible. It is Majroohs Yeh hai Bombay meri jaan that makes this song ours.

This awareness of the plight of songwriters set me on the idea of doing something that would put in perspective their invaluable contribution to Hindi cinema. It was then that I started thinking of doing a biography of one of the lyricists from the golden era of the Hindi film song, viz., the 1950s and the 1960s, all of whom were stalwarts in their own right. I actively sought reading material on each one of them towards this end. I then followed a process of elimination to narrow down on the choice of subject.

Majrooh Sultanpuri and Kaifi Azmi were amongst the first to be struck off the list. This is not because their work lacked in quality, but because I firmly believed that any attempt on my part to outline their legacy would pale in front of the efforts of their immediate families to do the same. Hasrat Jaipuri, too, from what I have read of him, is survived by family members, but his work did not have quite the same timbre that Majroohs or Kaifis lyrics possessed. A closer examination of his work also reveals that, working with the same music director duo of ShankarJaikishan for Raj Kapoor, Shailendra was able to create a far bigger impact than Hasrat. In fact, poetlyricistfilm-maker Gulzar rates Shailendra as probably the finest of film lyricists.

Jan Nisar Akhtars contributions were few and far between. If anything, the quality of the man is better gauged by his standing as an Urdu poet espousing the cause of the Progressive Writers Movement. And I must confess that during this exercise in elimination, I did not know much about Rajinder Krishan. This is a comment on my ignorance than on Rajinders quality as a songwriter. Over the course of my research for this book, I have learnt to appreciate Rajinders legacy, which now leads me to say that he remains perhaps the most unsung songwriter of his time.

Shakeel Badayuni was a difficult option to eliminate. The romantic essence of his songs was unmatched. But compared to the two lyricists left on my list, his work never quite touched me in the same way. Even so, it has to be admitted that Shakeel, like Majrooh and Kaifi, was one of the more difficult names to drop while selecting the subject for this book.

I was then left with Shailendra and Sahir Ludhianvi. It was now a question of selecting one who appealed to me the most.

Admittedly, Shailendra fascinated me more initially. He died really young, at the age of forty-three, in 1966. In this time, in a career spanning a little over fifteen years (the least in comparison to the aforementioned songwriters), Shailendra left an indelible imprint on our cinema through films like Shri 420 (1955), Madhumati (1958), Anari (1959) and Guide (1965). However, one catch remained: Shailendras family members have also planned a book on him, which influenced me in my decision to plump for Sahir.

But what clinched it for me in Sahirs favour was his personal life. He drew from his experiences to express himself through the medium of the film song. The memories of his childhood, his brush with the Progressive Writers Movement, his relationship with his mother and the other women in his life, were all channelized to his songwriting. This was in contrast to his peers who wrote, largely, as per the demands of the script. In a couplet, Sahir even admitted to being inspired from personal incidents in his poetry and, by extension, in his songwriting:

Duniya ne tajurbaat-o-havaadis ki shakl mein

Jo kuch mujhe diya hai, lauta raha hoon main

(Whatever the world by way of experience and accident

Has given me, I return it now)

Above all, Sahir was not without fault. His human side was never too far behind his brilliance as a songwriter. In the words of Pramila Le Hunte, one-time British politician and Indian national who in 2009 directed and presented the play Sahir: His Life and Loves in New Delhi, He had the gift of genius and the weakness of genius. Also, because he died a bachelor and did not leave behind any family to remind coming generations of his legacy, I felt compelled to repay my debts to a man who, through his songs in Pyaasa (1957), Hum Dono (1961), Waqt (1965) and Kabhi Kabhie (1976), has given me innumerable moments of joy.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Sahir Ludhianvi: The Peoples Poet»

Look at similar books to Sahir Ludhianvi: The Peoples Poet. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Sahir Ludhianvi: The Peoples Poet and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.