THE FALL OF ROME AND THE END OF CIVILIZATION

Bryan Ward-Perkins teaches History at Trinity College, Oxford. Born and brought up in Rome, he has excavated extensively in Italy, primarily sites of the immediately post-Roman period. His principal interests are in combining historical and archaeological evidence, and in understanding the transition from Roman to post-Roman times. A joint editor of The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. XIV, his previous publications include From Classical Antiquity to the Middle Ages, also published by Oxford University Press.

THE FALL OF ROME

AND THE END OF CIVILIZATION

BRYAN WARD-PERKINS

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox26DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

Bryan Ward-Perkins 2005

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published 2005

First published as an Oxford University Press paperback 2006

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organizations. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

Typeset by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk

Printed in Great Britain

on acid-free paper by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

ISBN 0-19-280728-5 (Pbk.) 978-0-19-280728-1 (Pbk.)

PREFACE

This book has taken an unconscionable time to write; but, as a result, it has had the benefit of being discussed with a large number of colleagues, and of being tried out in part on many different audiences in Britain and abroad. I thank all these audiences and colleagues, who are too many to name, for their advice and encouragement. I also thank the very many students at Oxford, who, over the years, have helped make my thinking clearer and more direct. The career structure and funding of universities in the UK currently strongly discourages academics and faculties from putting any investment into teachingthere are no career or financial rewards in it. This is a great pity, because, in the Humanities at least, it is the need to engage in dialogue, and to make things logical and clear, that is the primary defence against obscurantism and abstraction.

I owe a particular debt of gratitude to Alison Cooley, Andrew Gillett, Peter Heather, and Chris Wickham, for reading and commenting in detail on parts of the text, and, above all, to Simon Loseby, who has read it all in one draft or another and provided invaluable criticism and encouragement. I have not followed all their various suggestions, and we disagree on certain issues, but there is no doubt that this book would have been much the worse without their contribution.

The first half of this book, on the fall of the western empire, was researched and largely written while I held a Visiting Fellowship at the Humanities Research Centre in Canberra; this was a wonderful experience, teaching me many things and providing the perfect environment in which to write and think.

Katharine Reeve was my editor at OUP, and if this book is at all readable it is very much her doing. To work with a first-class editor has been a painful but deeply rewarding experience. She made me prune many of the subordinate clauses and qualifications that scholars love; and above all forced me to say what I really mean, rather than hint at it through delphic academic utterances. The book also benefited greatly from the very helpful comments of two anonymous readers for OUP, and from the Press highly professional production team. Working with OUP has been a real pleasure.

My main debt inevitably is to my family, who have put up with this book for much longer than should have been necessary, and above all to Kate, who has been endlessly encouraging, a constructive critic of my prose, and ever-helpful over difficult points.

Finally I would like to record my heartfelt gratitude to my friend Simon Irvine, who always believed I would write this book, and to the three men who, at different stages of my education, taught me a profound respect and love of History, David Birt, Mark Stephenson, and the late Karl Leyser.

Bryan Ward-Perkins

20 January 2005

CONTENTS

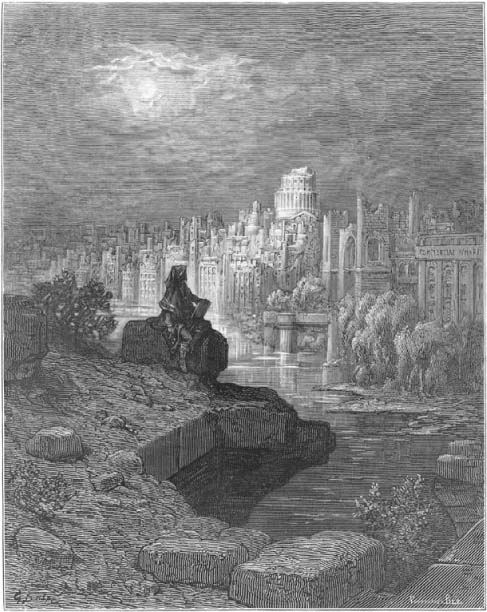

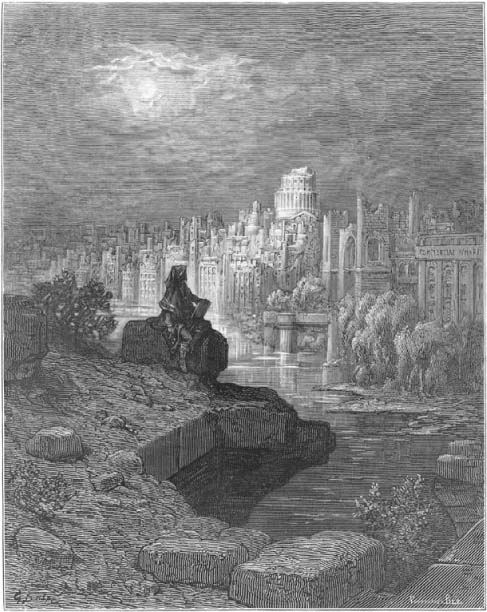

1.1 London in ruins, as imagined by Gustave Dor in 1873. A New Zealander, scion of a civilization of the future, is drawing the remains of the long-dead city.

I

DID ROME EVER FALL?

ON AN OCTOBER evening in 1764, after some intoxicating days visiting the remains of ancient Rome, Edward Gibbon sat musing amidst the ruins of the Capitol, and resolved to write a history of the citys decline and fall.).

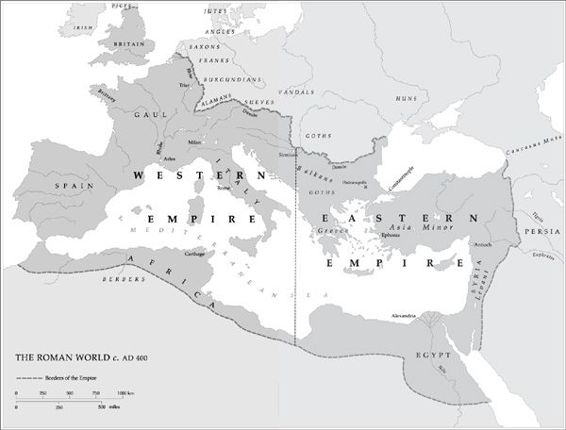

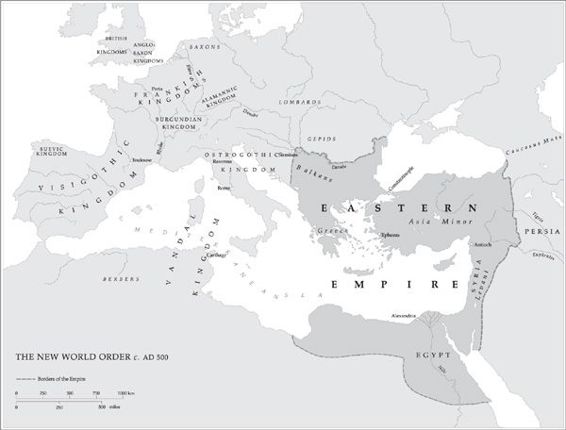

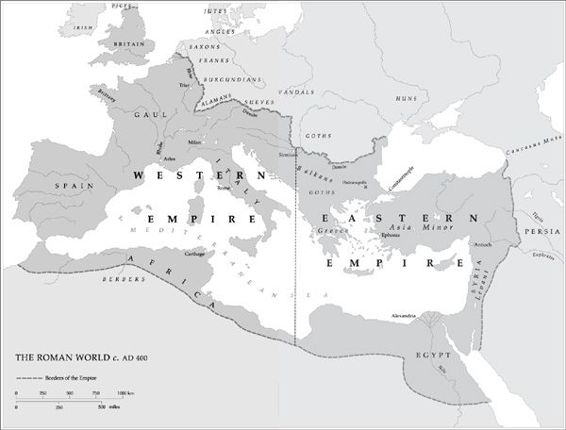

In Gibbons day, and until very recently, few people questioned age-old certainties about the passing of the ancient worldnamely, that a high point of human achievement, the civilization of Greece and Rome, was destroyed in the West by hostile invasions during the fifth century. Invaders, whom the Romans called quite simply the barbarians and whom modern scholars have termed more sympathetically the Germanic peoples, crossed into the empire over the Rhine and Danube frontiers, beginning a process that was to lead to the dissolution not only of the Roman political structure, but also of the Roman way of life.

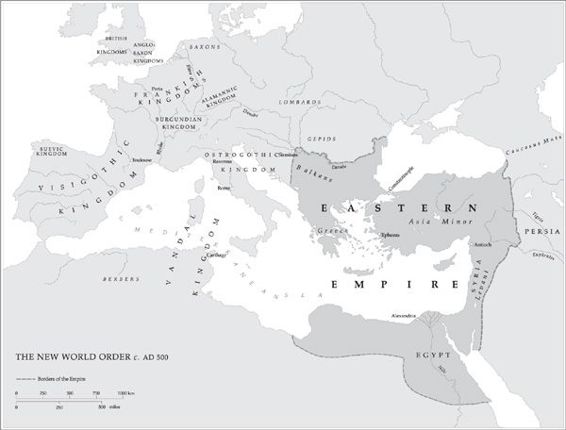

The first people to enter the empire in force were Goths, who in 376 crossed the Danube, fleeing from the nomadic Huns who had recently appeared on the Eurasian steppes. Initially the Goths threatened only the eastern half of the Roman empire (rule at the time being divided between two co-emperors, one resident in the western provinces, the other in the East (see front end paper)). Two years later, in 378, they inflicted a bloody defeat on the empires eastern army at the battle of Hadrianopolis, modern Edirne in Turkey, near the border with Bulgaria. In 401, however, it was the turn of the West to suffer invasion, when a large army of Goths left the Balkans and entered northern Italy. This began a period of great difficulty for the western empire, seriously exacerbated at the very end of 406, when three tribesthe Vandals, Sueves, and Alanscrossed the Rhine into Gaul. Thereafter there were always Germanic armies within the borders of the western empire, gradually acquiring more and more power and territorythe Vandals, for instance, were able to cross the Straits of Gibraltar in 429, and by 439 had captured the capital of Roman Africa.

Next page