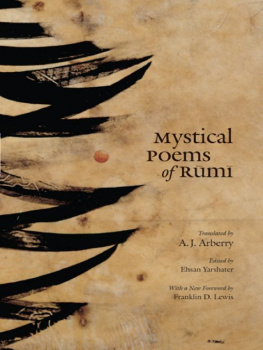

This is an excellent book which could easily be called the

definitive work on Rumi.

Ehsan Yarshater, Columbia University

There should be no doubt that this is a must for any serious

student of Rumi.

British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies

Solid scholarship, combined with an articulate and highly readable

style, will make this book accessible not merely to specialists

but to the general reading public.

Julie Meisami, University of Oxford

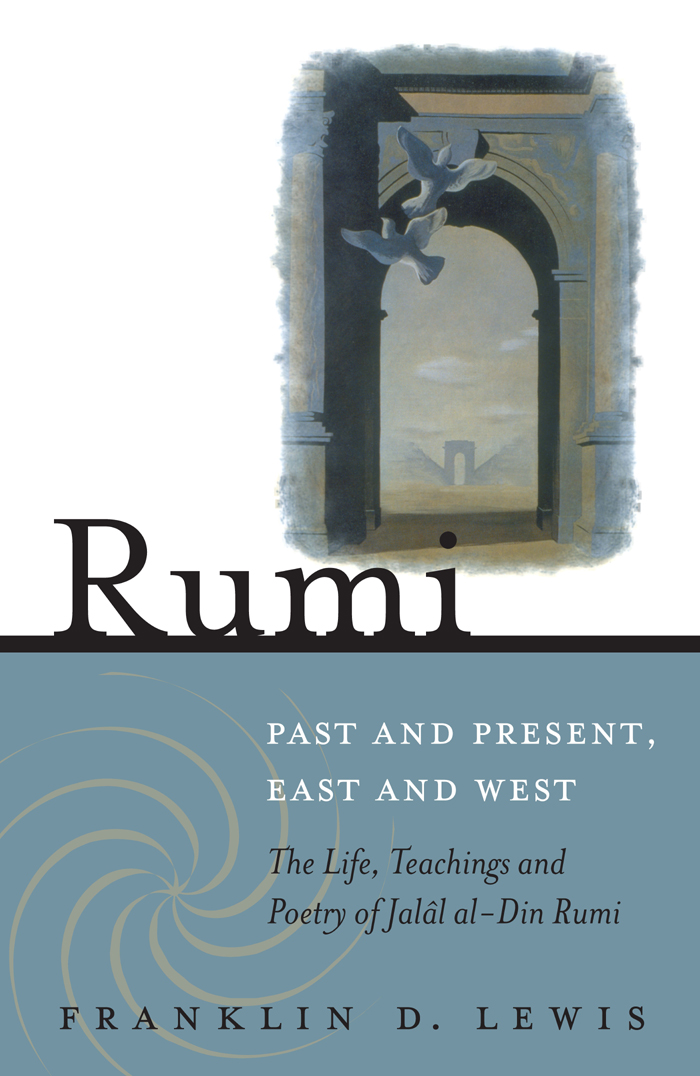

Franklin D. Lewis is Associate Professor of Persian in the Department of Middle Eastern and South Asian Studies at. Emory University in Atlanta, and an expert on Persian literature.

In 1995, his thesis on Sanai won the Best Dissertation of the Year Award from the Foundation for Iranian Studies; in 1996 he began work on the painstaking research that was to culminate in Rumi: Past and Present, East and West, published to critical acclaim from academics and general readers alike.

In 2001, for this book, Lewis received the British-Kuwait Friendship Society Award, handed out each year by the British Society of Middle Eastern Studies to the author of the best book on the subject published in Great Britain, becoming the first American in its four-year history to take home the award.

R u m i

PAST AND PRESENT,

EAST AND WEST

The Life, Teaching and Poetry of Jall alDin Rumi

FRANKLIN D. LEWIS

A Oneworld Book

First published by Oneworld Publications, 2000

This ebook edition published by Oneworld Publications, 2014

Copyright Franklin D. Lewis 2000, 2008

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available

from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-85168-549-3

Cover design by Design Deluxe

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

England

Stay up to date with the latest books,

special offers, and exclusive content from

Oneworld with our monthly newsletter

Sign up on our website

www.oneworld-publications.com

Contents

Foreword

Speech that rises from the soul, veils the soul. In this opening line of one of his ghazals Rumi voices the paradox which lies at the heart of his poetry: the inability of words, of language, to convey reality. Words interpose themselves between the soul and reality like the veil that conceals the beloveds face from the long-suffering lover; or (in another image from the same poem), like the shell which conceals the pith of meaning. Split the shell, so that you may arrive at meanings pith, counsels the poet; cleave through the flotsam and jetsam that floats, along with the foam, on the surface of the sea, to arrive at the purity of the seas depths. For Rumi, all of creation is a veil between the questing human being and the truth:

This transient world is a sign of the miracle of Truth;

but this same sign is a veil which hides the eternal Verities.

What are we to make of a poet who, while confessing to the impotence of language, and while constantly reiterating his reluctance to write poetry, is among the most prolific of the Persian poets: producing thousands of lyric ghazals, tens of thousands of narrative-didactic masnavi verses? The long history of discussion and scholarship on the poet both Eastern and Western has created many Rumis: the ecstatic mystic; the theosophist; the teacher and preacher; the Mevlevi dervish, lost in the whirling of the dance. Hagiographers (like Aflki, for example) have told of his miraculous acts; more sober writers have endeavored to make of the ideas expressed in his poems a theosophic system.

Who was Rumi? What was Rumi? Frank Lewiss study tries to reconstruct both the man and the poet, and does both, I think, highly successfully. Rumi was, first of all, an exile from his native land of Khorasan. He had travelled much in search of learning (which was, at the time, the common practice amongst Muslim scholars), and in search of teachers. At one point, he encountered the mysterious figure of Shams-e Tabrizi. Lewis, to his great credit, does much to untangle the mystery, and the myths, that surround Rumis relationship with this, his greatest teacher, and the name that instead of Rumis own, as might have been expected informs the closing lines of many of his ghazals.

Although existence is but a fragment of Shams-e Tabrizi,

it is a fragment which veils the soul from its source

Shams-e Tabrizi, you are the sun behind the cloud of words;

when your sun shows its face, the words become effaced.

Rumi was a teacher, with many disciples. He succeeded his father Bah Valad as head of what later became the Mevlevi order, and founded its ritual turning dance, for which many of his ghazals were composed. He was no ascetic, renouncing the world and its trappings to devote himself to pious observance in some remote and quiet corner; on the contrary, he was a frequenter of courts, of princes and high officials, to whom he offered spiritual advice. (Moreover, as Aflki tells it, on discovering he had been replaced as one princes spiritual advisor, Rumi went off in a huff and predicted a dire fate for the prince in question which, predictably, happened, although the account is, it seems, totally anachronistic).

In short, Rumi was many things as we might expect from a real person, rather than from a hagiographical saint-cum-hero or from more recent constructions of Rumi the mystic, Rumi the poet, and so on. He was, for one thing, a highly learned man, whose poetry even the lyric ghazals is not the rapturous outpourings of the ecstatic mystic, but can be highly complex. Thus it is that, when singing of the drunken camels who have been so entranced by the voice of the camel-driver that they have begun dancing, he relies on his audience to make the connection between these camels of God -the whirling mystics with the miraculous camel sent (so says the Koran) to the Arabian prophet Sleh, and which was hamstrung by Slehs people, who could not (or refused to) recognize this divine sign of his prophetic mission. Even so (we may interpret) do many people to recognize the divine nature of the mystics calling.

It is this complex and many-sided figure that Lewis attempts successfully, in my view to reconstruct in the present book. He appears to have read everything, in every relevant language, both by and about Rumi, and much related material besides (for example, the Maqlt of Shams-e Tabrizi himself, which gives at least verbal shape and form to this otherwise shadowy personage). He disentangles and debunks myths, misreadings and misrepresentations; not least, he gives due voice to Rumi the poet. For this is what remains to us (for most of us, who will not dig and delve into Rumis correspondence, or Shamss Maqlt, or other of the conflicting and contradictory source material): that vast outpouring of poetry which, despite Rumis own insistence on the impotence of language, shows his own constant engagement with it, his own attempt, if not to express, at least to point to the ineffable to what lies, as he so often puts it, on that side, the side which puts words into the mouth of the reed which sings its tales of separation from its source in the opening section of the Masnavi.