FIVE

CENTURIES

OF

KEYBOARD

MUSIC

FIVE

CENTURIES

OF KEYBOARD

MUSIC

An Historical Survey of Music for Harpsichord and Piano

JOHN GILLESPIE

Professor of Music, University of California

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC

NEW YORK

Copyright 1965 by Wadsworth Publishing Company, Inc.

All rights reserved.

This Dover edition, first published in 1972, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published in 1965. This new edition has been reprinted by special arrangement with Wadsworth Publishing Company, Inc., Belmont, California, publisher of the original edition.

International Standard Book Number: 0-486-22855-X

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 75-188812

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

22855X17

www.doverpublications.com

To my wife

ANNA

whose inspiration, encouragement, and help made this book possible

PREFACE

As a practicing harpsichordist and pianist, I have felt the need for a book that would provide a frame of reference for the music I play and also supply new ideas for additional repertoire. As a professor of music history and literature of keyboard music, I have wished for a book that might furnish suitable material for such courses. Finally, as one who has a great admiration for both piano and harpsichord music, I have looked for a book that might unfold a progressive panorama of keyboard music as it developed through the ages. There seemed to be no one book to fill these needs.

In this work I have endeavored to satisfy a wide range of interests. For the serious student of clavier literature, I have tried to give an idea of the different phases of keyboard development and to quote original sources whenever possible. For the musical amateur with a limited technical vocabulary, I have kept the text as simple as possible; since many terms are not necessarily self-explanatory, I have added a Glossary of pertinent musical terms. The more important musical formssonata, suite, fugueare discussed more fully in the text ().

The main content of the book is limited to harpsichord (also clavichord) and piano music. Organ music has its own niche and requires a separate volume. Therefore, the word keyboard is used to designate all stringed keyboard instruments, excluding the organ. The principal purpose of this book is to present a summary of music for solo keyboard. Ensemble music and compositions for keyboard and orchestra are also important and interesting; yet a thorough coverage of these would involve a separate book for each. The concerto form in general has been admirably explored by such writers as Abraham Veinus (London: Cassell & Co., Ltd., 1948) and Ralph Hill (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1961), each in a book titled The Concerto.

For the pianist or harpsichordistprofessional and amateurwho wishes to obtain the music discussed, I have indicated in the notes to each chapter where the compositions of each outstanding composer are published. At the end of the book is a list of the most important keyboard music publishers. Since it is impossible to maintain a current list of books and music in print, the reader is referred to the larger municipal and university libraries and to publishers catalogs for the most up-to-date listings. I have also included recent and unpublished dissertations as an important source of material; these are usually available on microfilm or in Xerox copies.

In a book of this scope it is impossible to discuss all the works of one specific composer, or to mention every composer who wrote a piano piece. I have tried to bring into focus composers who have written unusually attractive music or influenced the course of keyboard literature. Minor composers are introduced to complete the narrative.

My principal interest regarding the individual composers centers around their place of activity rather than their nationality. For example, Johann Schobert, a German-born composer, is placed in the chapter on France, since he worked mostly in that country.

Wherever feasible, I have tried to provide the compositions with original titles plus an English translation. And I have supplied English versions to all excerpts that originated in a foreign tongue.

For their help with some translations and proofreading, I want to thank Mr. and Mrs. Eduard Schmutzer. I also give my grateful thanks to Dr. Wendell Nelson and Dr. Roger Nyquist for their kindness in reading the manuscript; to Dr. Dolores Menstell Hsu for her careful study of the text and her helpful suggestions; and to the eminent Dr. Karl Geiringer for his final reading of the completed manuscript. A special note of gratitude goes to Mr. John de Keyser, owner of the de Keyser music shop in Hollywood, California, for his patient and knowledgeable assistance in searching out the vast repertoire of keyboard music.

CONTENTS

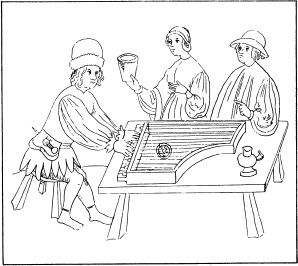

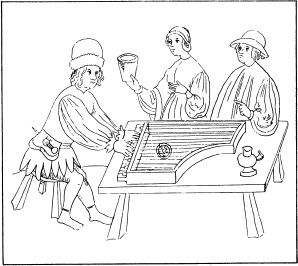

Ill. 1. CLAVICHORD from the Weimarer Wunderbuch, ca. 1440.

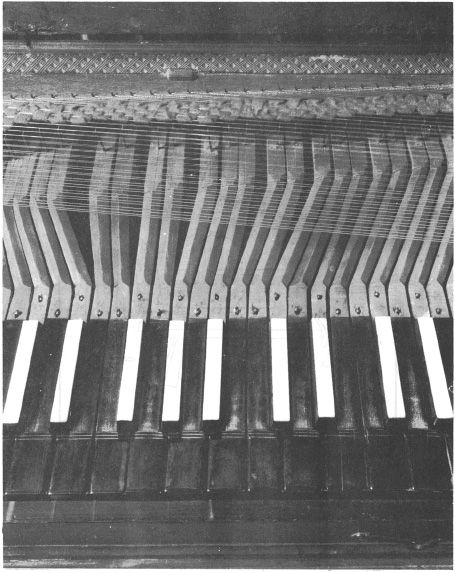

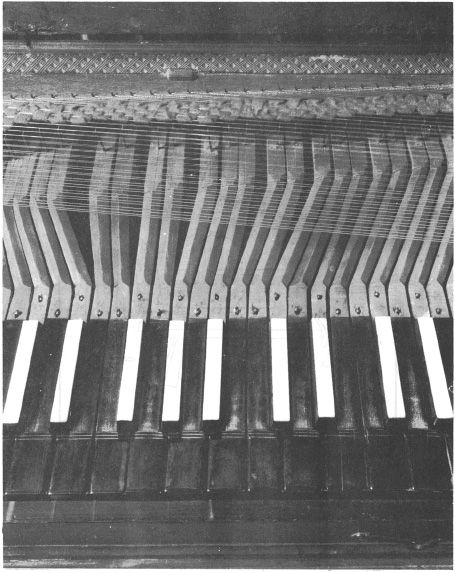

Ill. 2. FRETTED GERMAN CLAVICHORD, 18th century (close-up of action). Courtesy The Smithsonian Institution. Photograph by Robert Lautman.

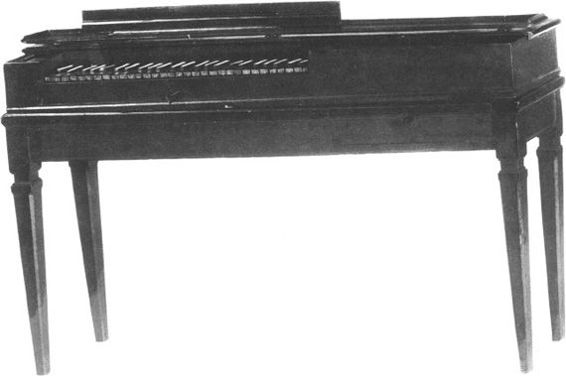

Ill. 3. FRETTED GERMAN CLAVICHORD, 18th century. Courtesy The Smithsonian Institution.

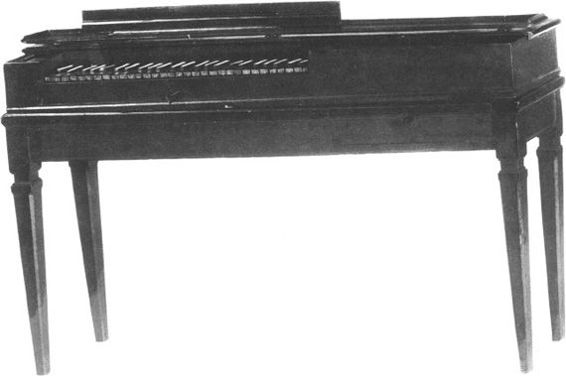

Ill. 4. UNFRETTED CLAVICHORD, late 17th or 18th century. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, 1889.

Ill. 5. HARPSICHORD from the Weimarer Wunderhuch, ca. 1440.

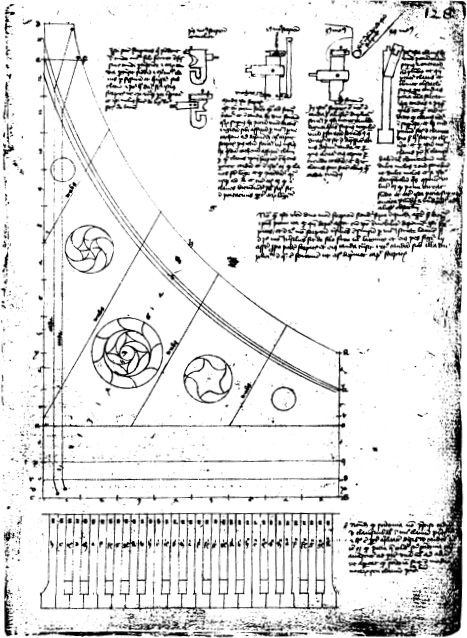

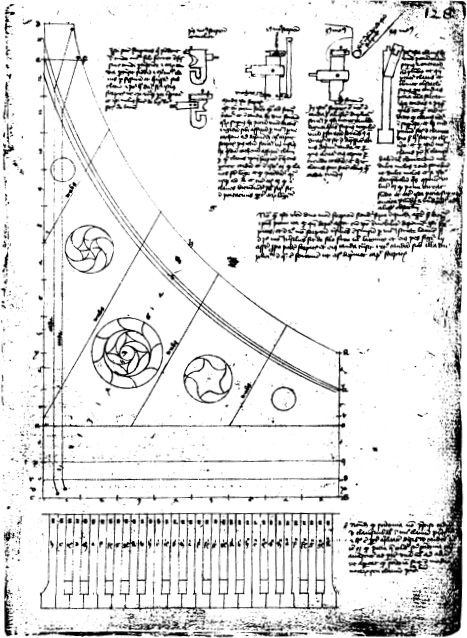

Ill. 6. DIAGRAM OF A HARPSICHORD by Henri Arnault de Zwolle, ca. 1440. Photograph courtesy The Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

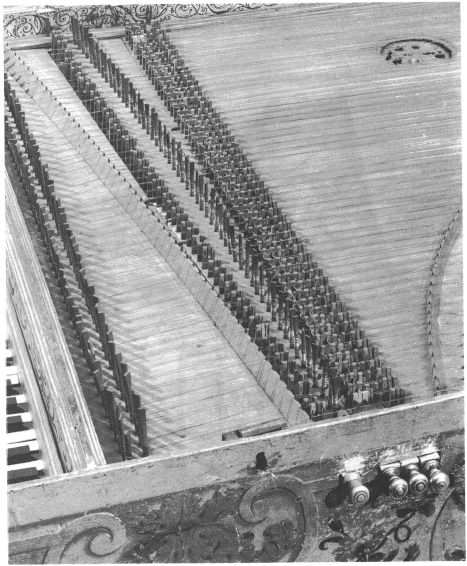

Ill. 7. ITALIAN HARPSICHORD, made in 1643. Inscribed on nameboard: Horatius Albana f. Anno MDCXXXIII. Courtesy The Smithsonian Institution.

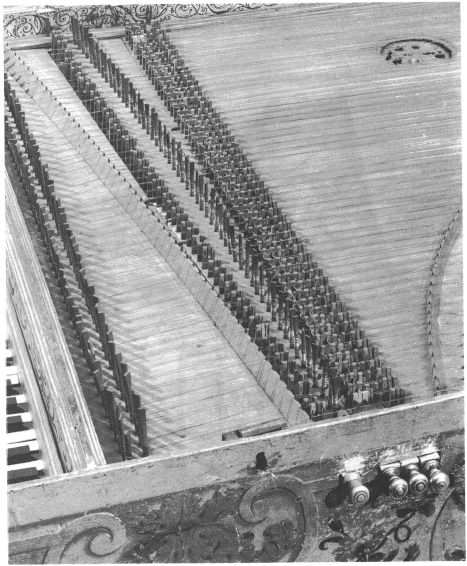

Ill. 8. TWO-MANUAL HARPSICHORD, made by Burkat Shudi, England, in 1747. Courtesy Hugo Worch Collection, The Smithsonian Institution.

Ill. 9. TWO-MANUAL HARPSICHORD, made by Johannes Daniel Dulcken, Belgium, in 1745. Courtesy Hugo Worch Collection, The Smithsonian Institution.

Ill. 10.

Next page