FOR ALLISON, NICK,

WILLIAM, AND LILLIAN

I.

THEME FOR A PAS DE DEUX

F REDERICK THE GREAT HAD ALWAYS LOVED TO PLAY the flute, which was one of the qualities in him that his father most despised. Throughout his youth, Frederick had to play in secret. Among his fondest memories were evenings at his mothers palace, where he was free to dress up in French clothes, curl and puff his hair in the French style, and play duets with his soulmate sister Wilhelminahe on the flute he called Principe, she on her lute Principessa. When Fredericks father once happened unexpectedly on this scene, he flew into a rage. Even more than his sons flute playing, Frederick William I hated everything FrenchFrench clothes, French food, French mannerisms, French civilization, all of which he dismissed as effeminate. He had of course been educated in French, like most German princes (he could not even spell Deutschland but habitually wrote Deusland), so he had to speak French, but he hated himself for it. He dressed convicts for their executions in French clothes as his own sort of fashion statement.

In this regard and others, Fredericks father was at least half mad. Flagrantly manic-depressive and violently abusive, he also suffered from porphyria, a disease common among descendants of Mary Queen of Scots (which he was, on his mothers side). Its afflictions included migraines, abscesses, boils, paranoia, and mind-engulfing stomach pains. The rages of Frederick William were frequent, infamous, and knew no rank: He hit servants, family members (no one more than Frederick), even visiting diplomats. Racked by gout, he lashed out with crutches, and if the pain was bad enough to put him in his wheelchair, he chased people down in it brandishing a cane. He was infamous for his caningshe left canes in various rooms of the castle so they would always be close at handbut he also threw plates at people, pulled their hair, slapped them, knocked them down, and kicked them. A famous story has him walking down the street in Potsdam and noticing one of his subjects darting away. He ordered the man to stop and tell him why he ran. Because he was afraid, the man said. Afraid?! Afraid?! Youre supposed to love me! Out came the cane and down went the subject, the king screaming, Love me, scum! Such a rage could be sparked by the very word France.

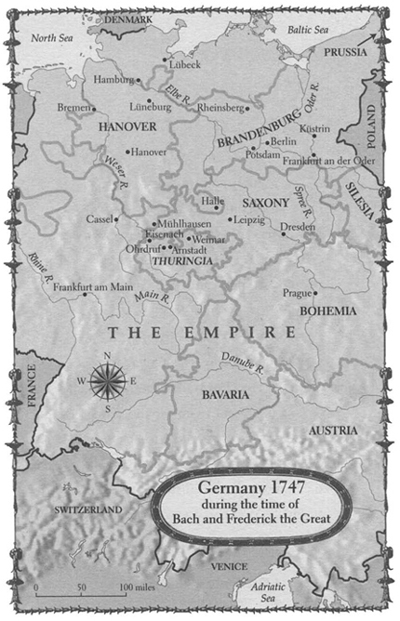

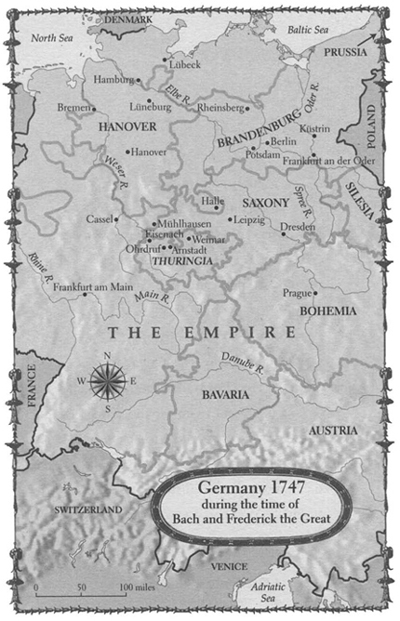

Not until his father died when Frederick was twenty-eight could he play his flute free from the threat of censure or attack, so naturally it was among his most beloved and time-consuming pastimes as king. With the musicians in his court Kapelle, who were not only the best in Prussia but the best he could buy away from Saxony and Hanover and every other German territory, he played concerts virtually every evening from seven to nine oclock, sometimes even on the battlefield. He cared as much about music as he cared about anything, except perhaps for war.

Having had both a love of the military and a cynical, self-protective ruthlessness literally beaten into him by his father, Frederick had already been dubbed the Great after only five years on the throne, by which time he had greatly enlarged his kingdom with a campaign of outrageously deceitful diplomacy and equally incredible military strokes that proved him a brilliant antagonist and made Prussia, for the first time, a top-rank power in Europe. A diligent amateur of the arts and literatureavid student of the Greek and Roman classics, composer and patron of the opera, writer of poetry and political theory (mediocre poetry and wildly hypocritical political theory, but never mind)he had managed also to make himself known as the very model of the newly heralded philosopher-king, so certified by none less than Voltaire, who described young Frederick as a man who gives battle as readily as he writes an opera. He has written more books than any of his contemporary princes has sired bastards; and he has won more victories than he has written books. Fredericks court in Potsdam fast became one of the most glamorous in Europe, no small thanks to himself, who worked tirelessly to draw around him celebrities (like Voltaire) from every corner of the arts and sciences.

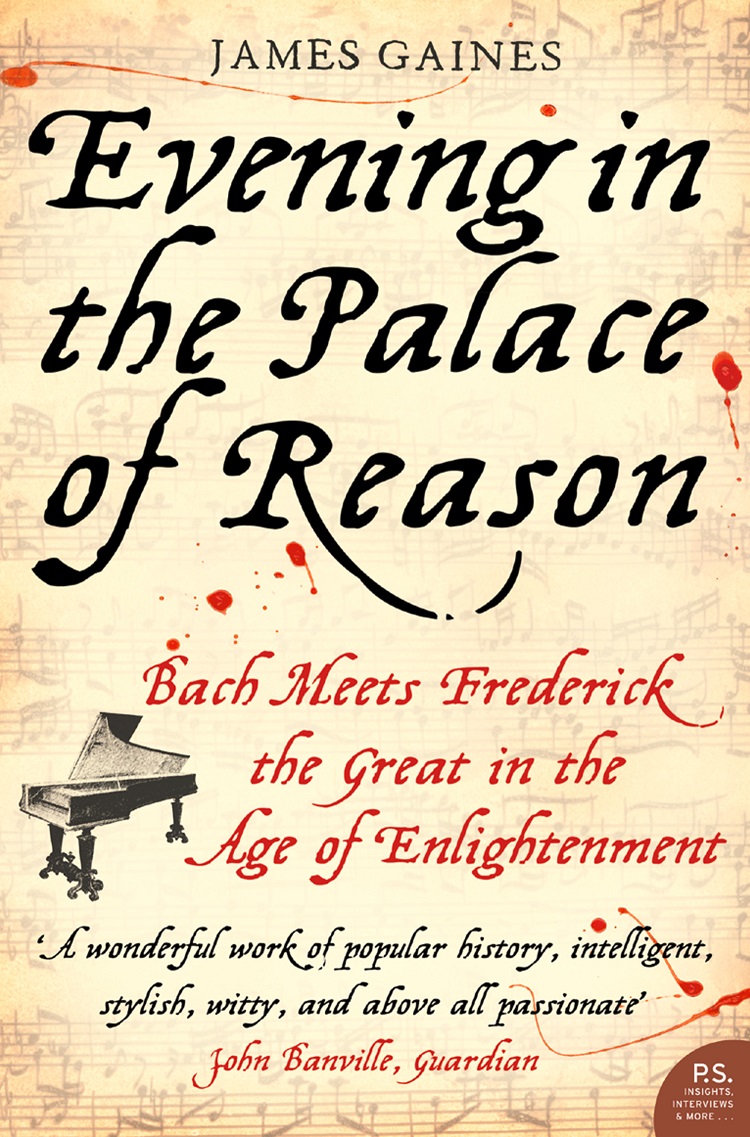

One Sunday evening in the spring of his seventh year as king, as his musicians were gathering for the evening concert, a courtier brought Frederick his usual list of arrivals at the town gate. As he looked down the list of names, he gave a start.

Gentlemen, he said, old Bach is here. Those who heard him said there was a kind of agitation in his voice.

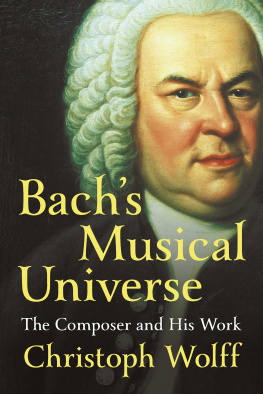

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH was sixty-two years old in 1747, only three years from his death, and making the long trip from Leipzig, which would be his last journey, was surely more a concession than a wish. An emphatically self-directed, even stubborn man, Bach took a dim view of this particular king, the Prussian army having overrun Leipzig less than two years before, and at his advanced age he could not have relished spending two days and a night being jostled about in a coach to meet the bitter enemy of his own royal patron, the elector of Saxony. Even more problematic than the political and physical difficulties of such a journey, though, the meeting represented something of a confrontation for the aging composera confrontation, one might say, with his age. In music and virtually every other sphere of life in mid-eighteenth-century Germany, Frederick represented all that was new and fashionable, while Bachs music had come to stand for everything ancient and outmoded. His musical language, teaching, and tradition had been rejected and denounced by young composers and theorists, even by his own sons, and Bach had every reason to fear that he and his music were to be forgotten entirely after his death, had indeed been all but forgotten already. For this reason and others, his encounter with Prussias young king threatened to bring into question some of the most important qualities by which he defined himself, as a musician and as a man. It would also present him the opportunity for one of the most powerful and eloquent assertions of principle he had ever made, but that would have been anything but clear to him at the time.

Bach came despite the challenges involved because Frederick was the employer of his son Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, the chief harpsichordist in Prussias royal Kapelle. Carl had been hired on when Frederick was still crown prince, hiding from his father the fact that he had any musicians and paying their salaries by borrowing secretly from foreign governments and padding his expenses. It was even then an extraordinary group, including the best composers and musicians of the modern generation, most of them well known tobut a good deal younger thanCarls father. Frederick had been hinting broadly that he would like to meet old Bach ever since Carl had come to work for him, and Carls letters home had reflected a growing concern that at some point the kings wish would become his command. But no one knew better than Carl just what a collision of worlds a meeting between his flashy, self-regarding employer and his irascible, deeply principled father would be.

There were very few similarities indeed between the young king and the old composer, but there was this one: They stood firm in their respective roles, their fields of work having been determined by long ancestry. The Hohenzollern dynasty had ruled in Germany for three hundred years before Frederick was born and would rule for two hundred more, to the end of World War I. The Bach line stretched from Luther across three centuries, and theirs too was a family business; more than five dozen Bachs held important musical positions in German towns, courts, and churches between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries.