NANCY MITFORD (19041973) was born into the British aristocracy and, by her own account, brought up without an education, except in riding and French. She managed a London bookshop during the Second World War, then moved to Paris, where she began to write her celebrated and successful novels, among them The Pursuit of Love and Love in a Cold Climate, about the foibles of the English upper class. Mitford was also the author of four biographies: Madame de Pompadour (1954), Voltaire in Love (1957), The Sun King (1966), and Frederick the Great (1970)all available as NYRB Classics. In 1967 Mitford moved from Paris to Versailles, where she lived until her death from Hodgkins disease.

LIESL SCHILLINGER is a journalist, critic, and translator. She is a regular contributor to The New York Times Book Review and has written on literature, culture, theater, politics, and travel for many publications, including The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Daily Beast, and The Independent on Sunday. Among her translations are The Lady of the Camellias by Alexandre Dumas (fils) and Every Day, Every Hour by Nataa Dragni. Her illustrated book of neologisms, Wordbirds, will be published in October 2013.

OTHER BOOKS BY NANCY MITFORD

PUBLISHED BY NYRB CLASSICS

Madame de Pompadour

Introduction by Amanda Foreman

The Sun King

Introduction by Philip Mansel

Voltaire in Love

Introduction by Adam Gopnik

FREDERICK THE GREAT

NANCY MITFORD

Introduction by

LIESL SCHILLINGER

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 1970 by Nancy Mitford

Introduction copyright 2013 by Liesl Schillinger

All rights reserved.

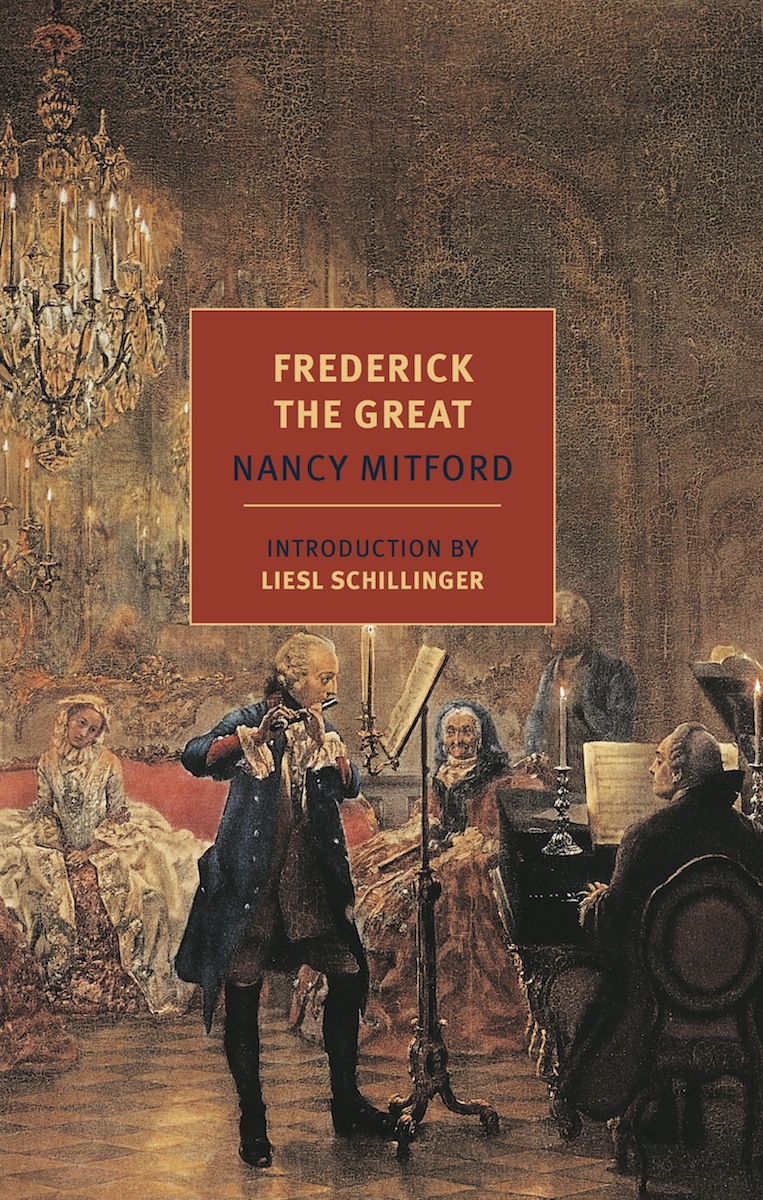

Cover image: Adolf von Menzel, Flute Concerto at Sans Souci, 1852; Frederick the Great plays flute, C. P. E. Bach accompanies him at the keyboard; Agostini Picture Library / The Bridgeman Art Library

Cover design: Katy Homans

The Library of Congress has cataloged the earlier printing as follows:

Mitford, Nancy, 19041973.

Frederick the Great / by Nancy Mitford ; introduction by Liesl Schillinger.

pages cm. (New York Review Books classics)

Originally published: London : Hamilton, 1970.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-59017-623-8 (alkaline paper)

1. Frederick II, King of Prussia, 17121786. 2. Prussia (Germany)Kings and rulersBiography. 3. Prussia (Germany)HistoryFrederick II, 17401786.

I. Title.

DD404.M57 2013

943'.053092dc23

[B]

2012048406

eISBN 978-1-59017-642-9

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

Introduction

In 1969, Nancy Mitford, the sparkling, supercilious British debutante turned novelist, began work on a biography of Frederick the Great, the eighteenth-century Prussian king who outfoxed the combined forces of France, England, Russia, and the Holy Roman Empire to make Prussia master of Germany. The reader who opens this book may wonder what attracted an apolitical Francophile socialite to a fearsome Teuton whose foes reviled him as a monster, a sodomite, a busybody, and the compleatest tyrant that God ever sent for a scourge; and whose friends (notably the French sage Voltaire) could be almost as uncomplimentary. Mitford and der alte Fritz (as his soldiers called him) hardly sound like a natural pairing.

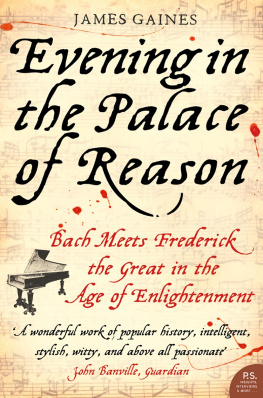

In a letter in March 1970, a few months before the publication of the Frederick biography, Nancy wrote to her sister Jessica that the BBC was about to interview her and planned to ask if her books were really a description of the Mitford family. Very true, Nancy wrote matter-of-factly: History is always subjective & the books we yawn over are often the descriptions of the home life of some dreary old professors. Mitfords own colorful, privileged life made her feel an affinity to the colorful, privileged men and women whose biographies she composed. These were not ordinary people, she remarks at the beginning of Voltaire in Love, her 1957 retelling of Voltaires long romance with the (married) philosopher and flirt, the Marquise du Chtelet. Her description of Voltairedroll, impertinent, inquisitive, dancing, elegant, and brittlemirrors the description many gave of Mitford herself. While reading up on Voltaire, she became intrigued by his fraught, self-serving friendship with Frederick the Great; she also became curious about the German leader. Frederick may not have been dancing, elegant, and brittle like Voltaire, but his character chimed with Mitfords in other ways. Said to be brilliant, teasing and aggressive, the king possessed a keen, intuitive intelligence and a social poise that inspired admiration but could also provoke suspicion and unease.

Born in London in 1904, raised in the Cotswolds on a country estate called Swinbrook, Mitford began in her twenties to write sharply observed, romantic, somewhat chilly, and very popular novels about the social world of the British aristocracy, the most celebrated of which would be The Pursuit of Love and Love in a Cold Climate. In 1946 she moved to Paris to be near her French loverthe (married) diplomat Gaston Palewskiand began writing a series of biographies about royal, noble, and notable figures of the ancien rgime, all of them, with the exception of Frederick, French. Her first was of Madame de Pompadour, the mistress of Louis XV. Her last, coming after a lavishly illustrated account of the reign of Louis XIV called The Sun King, was Frederick the Great.

Mitfords biographies are written in the same arch, conversational style one finds in her novels and letters: when her heroes and heroines quarrel and cry, they find themselves in floods (a well-worn Mitford family expression); a battle frontier may be deemed touchingly undefended; cruelty may be called naughtiness, while anything appealing will be delicious. Writing to her friend Hugh Thomas, the historian of the Spanish Civil War, Mitford dismissed Voltaire in Love as just a Kinsey report of his romps with Mme du Chtelet and her romps with Saint-Lambert and his romps with Mme de Boufflers and her romps with Panpan and his romps with Mme de Grafigny... I could go on for pages. And yet, for all her lightness of tone, she exposed her subjects shady trysts and mercenary motives not only with gossipy glee but with accuracy and rigor. In the case of Frederick, however, her intentions appear more ambitious, her tone gentler. Her aim seems to have been nothing less than the rehabilitation of a man whom she regarded as less popular with his contemporaries than he should have been and underappreciated in modern times.

Frederick II, the future king of Prussia, born January 24, 1712, was the third son of Frederick William I of Prussia and Sophia Dorothea of Hanover. (Sophia Dorothea, Mitford notes, was Englishthe daughter of George I, King of Great Britain and Ireland, and also was a gossip, a bore and a snob who spent years fruitlessly trying to marry off her Germanic children to their English cousins.) Frederick was the first of their male progeny to survive infancy. The first heir had died after a crown was jammed on his head at his christening; the second had been killed by the concussive effect of celebratory cannons fired too near his cradle. The crown prince himself barely made it through his teens. An attractive youth, clever, musical, high-spirited, and entranced by the aesthetic and philosophical charms of France, he in no way embodied his fathers brusque, ascetic male ideal. Frederick William I, anti-intellectual, anti-French, hostile to luxury, and bedeviled by gout and porphyric rages, regarded his son, according to Mitford, as a disobedient, effeminate fop. When the teenaged Frederick curled and fluffed his hair in the latest Versailles fashion, and studied Latin and flute in secret, his father beat him about the face with a cane, kicked him, and pulled his hair to teach him to respect Teutonic simplicity.