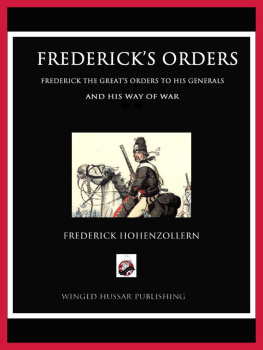

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2005, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by The Military Service Publishing Company, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in 1944.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Frederick II. King of Prussia, 1712-1786.

[Des Knigs von Preussen Majestt Unterricht von der Kriegs-Kunst

an seine Generals. English]

Instructions for his generals / Frederick the Great ; translated by

General Thomas R. Phillips.

p. cm.

Originally published: Harrisburg, Pa. : Military Service Pub. Co., 1944.

9780486163161

1. GeneralsGermanyPrussiaHandbooks, manuals, etc. 2.

Prussia (Kingdom). ArmeeOfficers handbooks. 3. Military art and sci

enceHandbooks, manuals, etc. 4. Command of troopsHandbooks,

manuals, etc. I. Title.

UB200.F74314 2005

355.02dc22

2005045465

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y 11501

Introduction

F REDERICK the Great, King of Prussia, was the founder of modern Germany. When he became King of Prussia it was a small state, in two parts, and of minor importance among the great powers of Europe. During his reign the population increased from 2,240,000 to 6,000,000, and the territory was increased by nearly thirty thousand square miles.

He fought all the great powers of Europe in the Seven Years War and successfully defended the national territory.

Although he gained no new lands during this war his success against the overwhelming coalition of his enemies made him a great man of his time and the soldier whom all other soldiers in Europe were to imitate. Fredericks upbuilding of Prussia determined whether the many small German states eventually were to group themselves around Prussia or around Austria. The expansion of Prussia was continued by Bismarck.

Frederick the Great, or Frederick II, was the grandson of Frederick I, the first King of Prussia. His family The Hohenzollcrns of Brandenburg, was founded by the Margrave Frederick, who began to rule in Brandenburg in 1415.

Successively the monarchs of the line and the years of their reigns and lives were:

1701-13, Frederick I; 1657-1713.

1713-40, Frederick William I, son of the above; 1688-1740.

1740-86, Frederick II, the Great; son of the above; 1712-1786.

1786-97, Frederick William II, nephew of the above; 1744-1797-

1797-1840, Frederick William III, son of above; 1770-1840.

1840-61, Frederick William IV, son of above; 1795-1861.

1861-1888, William I, brother of above; 1797-1888.

1888, March-June, Frederick III, son of above; 1831-1888.

1888-1918, William II, brother of above; 1859-1941.

Judgments of Fredericks qualities and merits, aside from those which bear upon his firmly-based renown as a military genius, differ widely amongst historians. The range of opinion runs from the extreme provided by Carlyles unstinted praise and admiration, which he found it impossible to express adequately in less than the seven volumes of his Frederick the Great, and which consumed thirteen years of his study and time, to that of another critic who roundly condemned the Prussian monarch as a canonized scoundrel.

Washington, Franklin and other American patriots of the Revolutionary era openly admired him. When he died Jefferson commented upon his death as an European disaster and as an event that affected the whole world. Washington welcomed Baron Steuben, and his assistance as drillmaster and tactician, as one of Fredericks soldiers.

These Americans had reason to feel kindly toward Frederick on score of the service which he undoubtedly rendered the rebellious colonies during the dark winter of Valley Forge, 1777-8. German soldiers from Hesse and Ansbach had been hired by the British for service in America. Frederick who was outspoken against Germans being sent from their native states to fight across seas, refused permission for a considerable body of German mercenaries to pass through Prussian territory to ports of embarkation. Troops that left Anspach in September, 1777, did not reach New York until October, 1778.

Frederick Hampered Howe

To quote from Frederick Kapps Frederick the Great and the United States, Leipsic, 1871: Washington was suffering all the hardships of his winter quarters at Valley Forge from December, 1777 to June, 1778. His weak force could not withstand a vigorous attack by Howe, but when Howe It irned of Fredericks prohibition of the passage of troops through Prussian territory he knew that that meant cutting off the prospects of any reinforcements. It was not the few men delayed in their journey that hampered Howe as much as the uncertainty about the coming of future German reinforcements. Fredericks policy was worth to Washington as much as an alliance, for it gave him time and helped to change the fortunes of war.

But, as Kapp explains, here without really wishing to do so, Frederick rendered a real service to the young republic. Frederick was playing a double game. For the time, he was at odds with England. But later, when he needed Englands help against Austria in the War of the Bavarian Succession (1778-9) he did authorize George the Thirds hired soldiers to proceed to America, by way of Prussia. He refused to recognize, in advance of the complete triumph of the colonists, the government of the rebels or to receive officially any of its representatives.

After the Revolution the popularity in America of Frederick was attested by number of inns with signs bearing the legend The King of Prussia. In Puritan New England and among the Germans of Pennsylvania and New York he was highly regarded as leader of Protestant resistance to Catholic aggression. Evidence is that Frederick never thought of anything but the interest of Prussia in the struggle between England and the American colonies.

One exploded legend is that, in token of his respect and admiration for Washington, he sent the American commander-in-chief a sword fashioned by a Prussian armorer. What happened was that a presentation sword was made by a German who commissioned his son to deliver it to Washington. The son left it in pawn to a Philadelphia tavern for thirty dollars. Friends of Washington redeemed it and it finally reached the Generals hands.

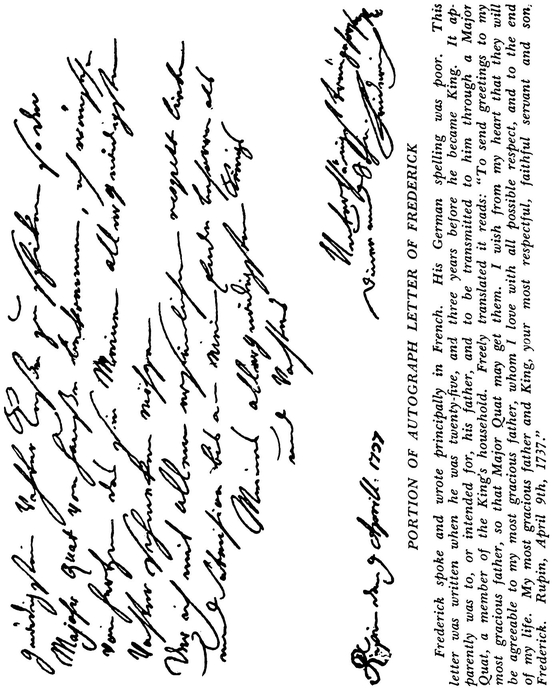

Fredericks father, Frederick William, brought him up with extreme rigor in the hope that he would become a hardy soldier and acquire thrift and frugality. To his fathers disgust he showed no interest in military affairs and devoted his time to literature and music. He was so harshly treated by his father that he resolved to escape to England and take refuge there. He was helped by two friends, Lieutenant Katte and Lieutenant Keith. The plan was discovered, and the Crown Prince was arrested, deprived of his rank, tried by court-martial and imprisoned in the fortress of Kustrin. Keith escaped, but Katte was captured, tried and sentenced to life imprisonment. The King changed the sentence and Frederick was forced to watch his friend beheaded.