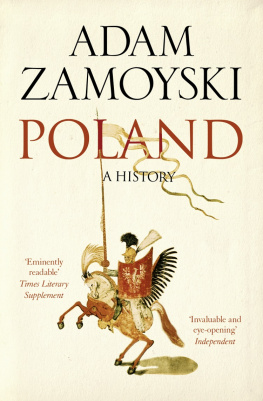

The Last King of Poland

Adam Zamoyski

Copyright Adam Zamoyski 1992

The right of Adam Zamoyski to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

First published in the United Kingdom in 1992 by Jonathan Cape.

This edition published in 2014 by Endeavour Press Ltd.

Table of Contents

Preface

Although an enormous amount has been written about various aspects of his reign, there is no satisfactory comprehensive biography of Stanisaw Augustus in any language. This is not surprising. The subject is so immense that it would require two fat volumes to begin to do it justice. My overriding feeling in writing this book has been one of frustration at not being able to dwell at requisite length on the many threads that make up this exceptional story. Much more needs to be written about Stanisaws political activities, about his influence on the hundreds of people with whom he worked and corresponded, about Polish politics, about the diplomatic kaleidoscope that swallowed up the Polish Commonwealth, about the relationship between the political awakenings in Poland, America and France, about the connections between the arts, sciences and thought that produced the cataclysms at the end of the century, and about the economic factors that underlay all of these. More work needs to be done in the archives and libraries of Poland, Russia, Germany and Austria before the real causes and effects of those events, and Stanisaws part in them, can be properly assessed. I can but hope that this book might be a step in that direction.

I have based my work principally on Polish and Russian archival sources, though for the latter I relied heavily on the remarkable 146 volumes of the Sbornik Imperatorskovo Russkovo Istoricheskovo Obschestva , as considerations of time and expense prevented me from delving into archives in Russia.

Dates are given in new style throughout, for simplicitys sake. I do not give the nobiliary titles borne by some Polish families, as these were rarely used at the time, and can only confuse the foreign reader as to the relative standing of families. Polish names appear in their original form, and I use the spelling of Seym current at the time in preference to the modern Sejm . Stanisaw himself is called Stanisaw August in Polish, Stanislas-Auguste in French, and usually Stanislas Augustus in English. Since he was actually Stanisaw II, to which he added Augustus in an allusion to his immediate predecessors and to the Roman emperor Augustus, I have decided to refer to him as Stanisaw Augustus.

I owe a debt of gratitude to the librarians and staff of the Archiwum Glwne Akt Dawnych and the Biblioteka Narodowa in Warsaw, the Biblioteka Czartoryskich in Krakw, the Bibliothque Polonaise in Paris, and the Polish Library and Polish Research Centre in London. I am grateful to Prince Philippe Poniatowski for permission to view the Poniatowski papers at the Archives Nationales in Paris. I am also grateful to Miss Joanna Wdke and Mr Jerzy Gutkowski of the Royal Castle in Warsaw for their assistance with obtaining the pictorial material. I should like to thank Mr Trevor Allen for the hard work he put into drawing the maps.

I am deeply indebted to Dr Andrzej Ciechanowiecki, Professor Andrzej Rottermund, and particularly Professor Andrzej Zahorski and Professor Isabel de Madariaga, for reading and commenting on my manuscript. I should also like to thank Shervie Price and Roger Hudson for their editorial help.

Adam Zamoyski

June, 1992

Note on Polish Pronunciation

Polish words may look complicated, but pronunciation is at least consistent. All vowels are simple and of even length, as in Italian, and their sound is best rendered by the English words sum ( a ), ten ( e ) , ease ( i ), lot ( o ) , book (u), sit (y).

The stress in Polish is consistent, and always falls on the penultimate syllable.

Most of the consonants behave in the same way as English, except for c , which is pronounced ts; j , which is soft, as in yes; and w, which is equivalent to English v. As in German, some consonants are softened when they fall at the end of a word, and b , d , g , w , z become p , t , k , f , s respectively.

There are also a number of accented letters and combinations peculiar to Polish, of which the following is a rough list:

= u , hence Krakw is pronounced krakooff.

= nasal a , hence sad is pronounced sont.

= nasal e , hence Lczyca is pronounced wenchytsa.

= ch as in cheese.

cz = ch as in catch.

ch = guttural h as in loch.

= English w , hence Bo e aw becomes Boleswaf, odz Wootj

= soft n as in Spanish maana

rz = French j as in je

= sh as in sheer.

sz = sh as in bush.

= as rz .

= A similar sound, but sharper as in French gigot .

Abbreviations

ANP Archives Nationales , Paris; Archives Poniatowski

AGAD Archiwum Glwne Akt Dawnych

AKP Archiwum Krlewstwa Polskiego

AK Archiwum Kameralne

ML Metryka Litewska

ZP Zbiory Popielw

APP Archiwum Publiczne Potockich

ASK Archiwum Skarbu Koronnego

AKJP Archiwum Ksiecia Jzefa Poniatowskiego

AXC Archiwum Xiazat Czartoryskich , Krakw

BM British Museum, London

BN Biblioteka Narodowa , Warsaw

BNBOZ Biblioteka Ordynacji Zamoyskiej

BP Bibliothque Polonaise , Paris

BPMAM Muzeum Adama Mickiewicza

BUW Biblioteka Unitversytetu Warszawskiego

Mmoires Stanisaw II Augustus, Mmoires du Roi Stanislas - Auguste Poniatowski , Vol. I, St Petersburg 1914, Vol. II, Leningrad 1924

Mmoires Mmoires Secrets et Inedits de Stanislas Auguste , Leipsig 1862

Secrets

MNW Muzeum Narodowe , Warsaw

Newport Newport Central Reference Library, Williams Papers

PAU Polska Akademia Umiejetnoci , Krakw

PRO Public Record Office, London

SPS tate Papers

PSI Polish Scientific Institute, New York

UV University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va

Chapter One Bedchambers and Cabinets

On the night of 28 December 1755 Stanisaw Poniatowski, the twenty-three-year-old secretary to the English ambassador in St Petersburg, set off on a clandestine escapade that was to alter the course of history.

He left his lodgings secretly, climbed into a sleigh with Lev Alexandrovich Naryshkin, and drove towards the Winter Palace. The sleigh stopped a little way from the palace, and Poniatowski followed his companion on foot through the snow to a side entrance. They passed a sentry, climbed the servants staircase, and went into the private apartments of the Grand Duchess Catherine Alekseyevna. Naryshkin, who bore the rank, appropriately it seems, of Gentleman of the Bedchamber to the grand duchess, showed him in and then vanished. Poniatowski was nervous at meeting her alone for the first time. He was also terrified. He had heard stories of savage punishments meted out to those who had incurred imperial displeasure, and visions of Siberian mines haunted him.

In the bedroom he found a young woman of twenty-five, dressed in a simple white satin gown trimmed with lace and pink ribbons. She had reached that moment when beauty is at its height in any woman to whom it has been granted. With black hair, she had a complexion of radiant whiteness and a high colour; she had large, prominent and very expressive blue eyes; long black eyelashes, a Greek nose, a mouth that seemed to beg for a kiss, perfect hands and arms, a slender figure, tall rather than small, a vivacious yet deeply noble deportment, a pleasant voice and a laugh that was as gay as her humour, he wrote. Such was the mistress who became the arbiter of my destiny.

That night they became lovers. Seven years later, she became Empress of all the Russias, and two years after that she used her influence and her troops to place Stanisaw Poniatowski on the throne of Poland. These two philosophical beings seem made to be united, wrote Voltaire, dreaming of a match that would give birth to a great northern utopia. Yet the story that began in love and mutual esteem ended forty years later in misunderstanding and recrimination. Catherine humiliated Stanisaw, carved up his kingdom, and erased the name of Poland from the map of Europe.

Next page