EVE BABITZ is the author of several books of fiction, including Sex and Rage: Advice to Young Ladies Eager for a Good Time; L.A. Woman; and Black Swans: Stories. Her nonfiction works include Fiorucci, The Book and Two by Two: Tango, Two-Step, and the L.A. Night. She has written for publications including Ms. and Esquire and in the late 1960s designed album covers for the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, and Linda Ronstadt. Her novel Slow Days, Fast Company: The World, the Flesh, and L.A. (originally published in 1977) is forthcoming from NYRB Classics.

HOLLY BRUBACH is the author of Choura: The Memoirs of Alexandra Danilova; Girlfriend: Men, Women & Drag; and A Dedicated Follower of Fashion, a collection of essays. Formerly Style Editor of The New York Times Magazine, she has been a staff writer for The New Yorker and The Atlantic Monthly, as well as a frequent contributor to numerous magazines. She lives in Pittsburgh.

EVES HOLLYWOOD

EVE BABITZ

Introduction by

HOLLY BRUBACH

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 1972, 1974 by Eve Babitz

Introduction copyright 2015 by Holly Brubach

All rights reserved.

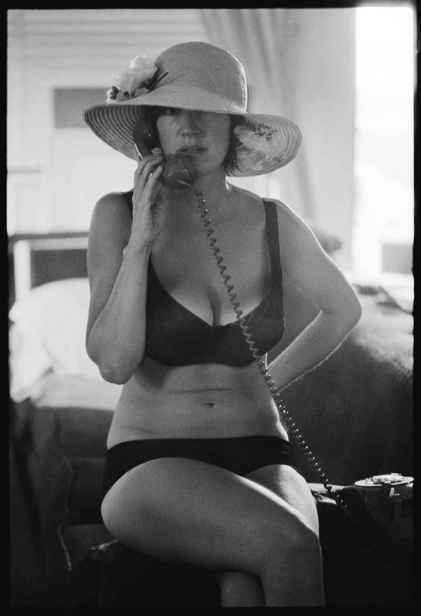

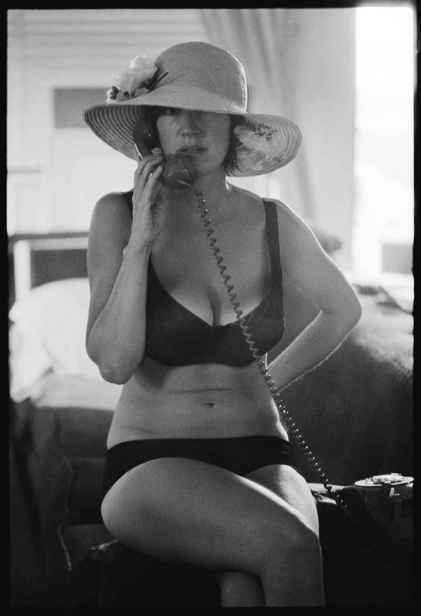

Frontispiece and concluding photographs of the author by Annie Leibovitz; Annie Leibovitz/(Contact Press Images)

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Babitz, Eve.

Eves Hollywood/Eve Babitz; introduction by Holly Brubach.

1 online resource.(New York Review Books classics)

ISBN 978-1-59017-891-1 (epub)ISBN 978-1-59017-890-4 (paperback)

1. Single womenFiction. 2. Hollywood (Los Angeles, Calif.)Fiction. I. Title.

PS3552A244

813'.54dc23

2015021808

ISBN 978-1-59017-891-1

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

To those of us growing up in the Northeast in the 1960s, California was a foreign country and Los Angeles its capital. Actual foreign capitals like London and Paris seemed more familiar. At the root of our deep mistrust was the Yankee conviction that weather is a defining force in shaping human characterthat harsh winters instill Calvinist rigor in those obliged to withstand them, that perpetual summer would inevitably corrode morals and the will to work. All those hillsides ablaze, those earthquakes rattling the china, struck us as fire-and-brimstone reminders that people were never meant to live in LA in the first placereminders unheeded by the local residents, a bunch of confirmed hedonists who lived in the moment, turning their backs on Europe and the past, facing the sunset and the sea.

In short, there was nothing about LA that would have led us to expect that a serious writer could emerge from it. Until one did, and rose to fame as an exalted practitioner of the inventive, highly personal journalism that dominated the 1970s. That was Joan Didion, whose name, alongside her husbands, appears in the roll call of dedications with which Eve Babitz opens this book: To the Didion-Dunnes for having to be who Im not. Didion, along with John Gregory Dunne, had decamped to New York, and from that distant vantage she wrote about Los Angeles in terms that flattered us Northeasterners into believing wed been right all along.

It was Babitz who finallyunapologeticallygave voice to LAs unique appeal and laid to rest the by then weary notion of the city as a cultural wasteland. For this, she was supremely qualified. With a father who was a baroque musicologist and violinist under contract to Twentieth Century-Fox, a mother who was an artist, and a godfather who was Igor Stravinsky, Babitz grew up surrounded by a circle of illustrious family friends that included Edward James, Joseph Szigeti, Eugene Berman, Marilyn Horne, Kenneth Rexroth, and Kenneth Patchett, with poetry readings in the living room and premieres of works by Arnold Schoenberg under the palms.

As it happened, this daughter of bohemians was also a child of Hollywood in its flickering grandeur, before a strip mall replaced the Garden of Allah hotel, where Eve and her friend Sally, two virgins with fake IDs, used to go to drink and practice their charms on men twice their age. Illusiona papier-mch coconut grove in a supper club, a restaurateur who claimed kinship to the late Russian tsarbecame reality when a quorum bought into it. You had to admire the daring, the imagination, the sheen of the veneer. At Hollywood High, Babitzs alma mater, the mascot was not, in the tradition of sports teams everywhere, an animal known for its ferocity but the title character of a Rudolf Valentino movie, The Sheikan Arab chieftain played by an epicene Italian actor. Seduction and glamour were woven into Babitzs everyday life, and they shaped her.

She idolized Marilyn Monroe, joined the crowd that turned out to see her plant her hands in wet cement at Graumans Chinese Theatre, fumed over proclamations of Arthur Millers genius while Monroes intelligence got short shrift. Like Monroe, Babitz must have had her fair share of men talking to her chest. Little did they know that just north of her magnificent breasts was the brain of a future novelist who would earn the admiration of her fellow writers. I was pretty and smart and scornful and impatient, she says of her teenage self. As qualifications for writing go, these turn out to be good oneseven her looks, which allowed her to pass as a spy in the land of the privileged, a member of an elite to which, she insists, she has never really belonged.

Monroe may have been her role model, but it was Brigitte Bardot that Babitz resembled. You can see it in her high-school yearbook photothe blond tousle, the heart-shaped face, the black-rimmed eyes. While most teenagers face the world head-on, gazing eagerly into the future, Babitzs gaze is sidelong, caught in a quiet smile of complicity with someone outside the frame. This seems in keeping with the confidential tone that makes Eves Hollywood feel like a series of soliloquies delivered by a friend over fruity drinks in a dark corner of the Luau, an ersatz Polynesian restaurant that was Stravinskys favorite.

Nobody writes about high school and the dimly lit passage from innocence to adulthood better than Babitz. Scrupulous and unsentimental but sympathetic to her former self, she documents that brief space of a few years when fledgling minds attempt to make sense of authority, social hierarchy, injustice, and sex. Against the backdrop of her own bourgeois claustrophobia, it is the outlaws (James Dean being the prototype and her hero) who command Babitzs fascination and respect. Drawn into the force field surrounding Aces Butler, a transfer student with a stratospheric IQ, an alias, and an attitude problem, she inventories his charisma: Who could resist the way he threw back his head and slapped his thigh in unheard-of abandon, in our starved colony? He dressed in black, black motorcycle jacket, black shirts, black Levis and black boots with his black eyelashes framing his acetylene eyes that flickered out in pure hate at the concepts of anything being for your own good or anyone who knew best.

Babitz is interested in power, and from Aces she learns that self-possession is one source of it. Beauty is another. The girls at Hollywood High were beautiful, extraordinarily beautiful. And there were about 20 of them who separately would cause you to let go of reason. Togetherand they stayed pretty much togetherthey were the downfall of any serious attempt at school in the accepted sense, and everyone knew it. They were too beautiful for a high school... For those of us who have wondered why it is that Southern California seems stocked with a disproportionately high percentage of ravishing women, Babitz offers a supremely logical explanation: These were the daughters of people who were beautiful, brave, and foolhardy, who had left their homes and traveled to movie dreams. In the Depression, when most of them came here, people with brains went to New York and people with faces came West. So Los Angeles became an experiment in genetic self-selectiona breeding ground for physical perfection, where the beautiful mated with the handsome, begetting successive generations, each exponentially better-looking than the one before.

Next page