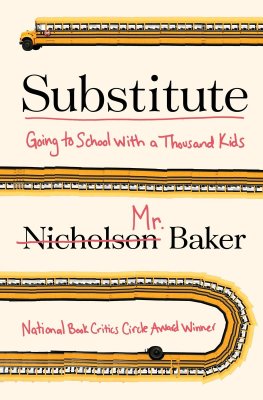

Also by Nicholson Baker

Checkpoint

A Box of Matches

Double Fold

The Everlasting Story of Nory

The Size of Thoughts

The Fermata

Vox

U and I

Room Temperature

The Mezzanine

SIMON & SCHUSTER

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright 2008 by Nicholson Baker

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Baker, Nicholson.

Human smoke: the beginnings of World War II, the end of civilization / Nicholson Baker.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. World War, 19391945Causes. 2. JewsPersecutionsEuropeHistory. I. Title.

D741.B255 2007

940.53'11dc22 2007044108

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-8396-7

ISBN-10: 1-4165-8396-3

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

Human Smoke

Contents

A LFRED N OBEL, the manufacturer of explosives, was talking to his friend the Baroness Bertha von Suttner, author of Lay Down Your Arms. Von Suttner, a founder of the European antiwar movement, had just attended the fourth Worlds Peace Conference in Bern. It was August 1892.

Perhaps my factories will put an end to war even sooner than your congresses, Alfred Nobel said. On the day when two army corps may mutually annihilate each other in a second, probably all civilized nations will recoil with horror and disband their troops.

S TEFAN Z WEIG, a young writer from Vienna, sat in the audience at a movie theater in Tours, France, watching a newsreel. It was spring 1914.

An image of Wilhelm II, the Emperor of Germany, came on screen for a moment. At once the theater was in an uproar. Everybody yelled and whistled, men, women, and children, as if they had been personally insulted, Zweig wrote. The good-natured people of Tours, who knew no more about the world and politics than what they had read in their newspapers, had gone mad for an instant.

Zweig was frightened. It had only been a second, but one that showed me how easily people anywhere could be aroused in a time of a crisis, despite all attempts at understanding.

W INSTON C HURCHILL, Englands first lord of the admiralty, instituted a naval blockade of Germany. The British blockade, Churchill later wrote, treated the whole of Germany as if it were a beleaguered fortress, and avowedly sought to starve the whole populationmen, women, and children, old and young, wounded and soundinto submission. It was 1914.

S TEFAN Z WEIG was at the eastern front, gathering Russian war proclamations for the Austrian archives. It was the spring of 1915.

Zweig boarded a freight car on a hospital train. One crude stretcher stood next to the other, he wrote, and all were occupied by moaning, sweating, deathly pale men, who were gasping for breath in the thick atmosphere of excrement and iodoform. There were several dead among the living. The doctor, in despair, asked Zweig to get water. He had no morphine and no clean bandages, and they were still twenty hours from Budapest.

When Zweig got back to Vienna, he began a pacifist play, Jeremiah. I had recognized, Zweig wrote, the foe I was to fightfalse heroism that prefers to send others to suffering and death, the cheap optimism of the conscienceless prophets, both political and military who, boldly promising victory, prolong the war, and behind them the hired chorus, the word makers of war as Werfel has pilloried them in his beautiful poem.

J EANNETTE R ANKIN OF M ONTANA, the first woman to be elected to the House of Representatives, voted against declaring war on Germany. It was April 6, 1917.

I leaned over the gallery rail and watched her, said her friend Harriet Laidlaw, of the Woman Suffrage Party. She was undergoing the most terrible strain. Almost all of her fellow suffrage leaders, including Laidlaw, wanted her to vote yes.

There was a silence when her name was called. I want to stand by my country, Rankin said. But I cannot vote for war. I vote no. Fifty other members of the House voted no with her; 374 voted yes. I felt, she said later, that the first time the first woman had a chance to say no to war she should say it.

One of her home-state papers, the Helena Independent, called her a dupe of the Kaiser, a member of the Hun army in the United States, and a crying schoolgirl.

A YOUNG PRO-WAR PREACHER, Harry Emerson Fosdick, wrote a short book, published by the Young Mens Christian Association.

War was not gallantry and parades anymore, Reverend Fosdick said. War is now dropping bombs from aeroplanes and killing women and children in their beds; it is shooting by telephonic orders, at an unseen place miles away and slaughtering invisible men. War, he said, is men with jaws gone, eyes gone, limbs gone, minds gone.

Fosdick ended his book with a call for enlistment: Your country needs you, he said. It was November 1917.

M EYER L ONDON, a socialist in the House of Representatives, voted no to President Wilsons second declaration of war, against Austria-Hungary. It was December 7, 1917.

In matters of war I am a teetotaler, said London, in a fifteen-minute speech. I refuse to take the first intoxicating drink.

Representative Walter Chandler walked over to where London sat and stood in front of him as he delivered his rebuttal.

It has been said that if you will analyze the blood of a Jew under the microscope, you will find the Talmud and the Old Bible floating around in some particles, Congressman Chandler said. If you analyze the blood of a representative German or Teuton you will find machine guns and particles of shells and bombs floating around in the blood.

There was only one thing to do with the Teutons, according to Chandler: Fight them until you destroy the whole bunch.

E LEANOR R OOSEVELT and her husband, Franklin D., the assistant secretary of the navy, were invited to a party in honor of Bernard Baruch, the financier. Ive got to go to the Harris party which Id rather be hung than seen at, Eleanor wrote her mother-in-law. Mostly Jews. It was January 14, 1918.

A CAPTURED G ERMAN OFFICER was talking to a reporter for The New York Times. It was November 3, 1918, and the German government had asked for an armistice.

The German officer claimed that his army was not defeated and should have continued the war. The Emperor is surrounded by people who feel and talk defeat, the officer said. He mentioned men like Philipp Scheidemann, the leader of the socialists.

New tanks were coming, the captured officer observed, and war was expected between the United States and Japan. Japan and the United States would surely clash some day, he said, and we would then furnish both sides with enormous quantities of material and munitions. The ceding of Poland and Alsace-Lorraine, the officer believed, meant social upheaval, the ruin of German industry, and the impoverishment of the working class. Our enemies will have what they have desiredthe complete annihilation of Germany. That would be a peace due to Scheidemann.

W INSTON C HURCHILL, now Englands secretary of state for war and air, rose in Parliament to talk about the success of the naval blockade. It was March 3, 1919, four months after the signing of the armistice that ended the Great War.

We are enforcing the blockade with rigour, Churchill said. It is repugnant to the British nation to use this weapon of starvation, which falls mainly on the women and children, upon the old and the weak and the poor, after all the fighting has stopped, one moment longer than is necessary to secure the just terms for which we have fought. Hunger and malnutrition, the secretary of war and air observed, had brought German national life to a state of near collapse. Now is therefore the time to settle, he said.

Next page