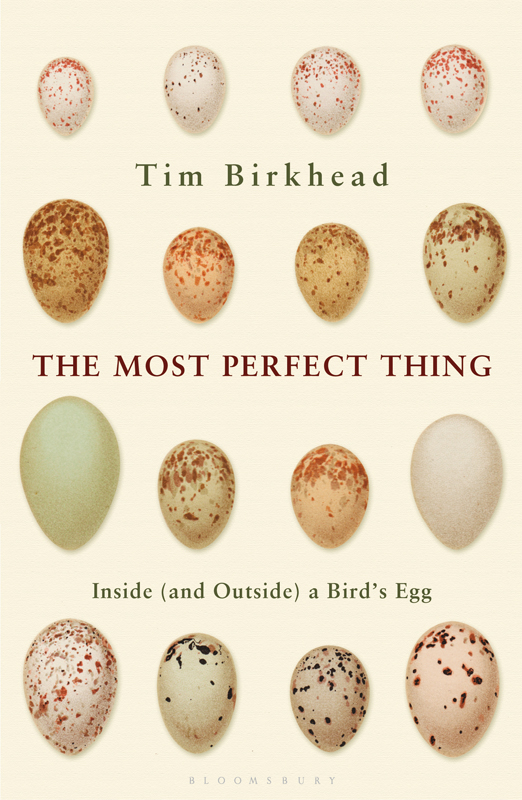

THE MOST PERFECT THING

THE MOST PERFECT THING

Inside (and Outside) a Birds Egg

Tim Birkhead

For my mother and for Erick Greene

Contents

This book has had a long incubation but was spun into life by a chance encounter. I was watching a wildlife programme on television one evening in 2012 when a well-known presenter appeared beside a cabinet of eggs in a museum. Opening one of the drawers, he took out an egg. It was white, I remember, and he held it to the camera to demonstrate its size and unusual pointed shape. This is a guillemots egg, he announced, and the reason he said for its extraordinary shape is so that it will spin on its axis and not roll off the narrow cliff ledge on which guillemots breed. To demonstrate, he placed the egg on the surface of the cabinet and spun it, and, sure enough, the egg rotated on the spot like a horizontal top.

I could not believe what I had just seen. Not because it is amazing, but because I was aghast that someone so revered for his natural history knowledge could make such a mistake. The spinning-on-the-spot story for guillemot eggs was debunked over a century ago, and here it was being given new life to an audience of millions.

You can spin a guillemot egg on its long axis, especially if, like the television presenter, you are using a blown (empty) museum egg. But that is not how a real egg full of either yolk and albumen or a developing embryo operates.

When I wrote to the presenter pointing out that what he had told us was wrong his initial response was understandably grumpy. I offered to send him the scientific papers on this topic so he could read the relevant research. I was about to post them when I had a sudden crisis of confidence. Here I was telling a television star how to behave when I could be wrong myself. I decided to reread the papers.

I have studied guillemots continuously since the early 1970s, in England, Wales, Scotland, Newfoundland, Labrador and the Canadian High Arctic. Ive lived and breathed guillemots for forty years and Ive read pretty well everything that has been written about them. I last looked at the articles dealing with guillemot egg shape twenty years previously, which is why I suddenly questioned my memory and decided to reread them. It was just as well I did, for the data and conclusions were both opaque and much messier than I remembered. I was also shocked by the realisation that most of those scientific papers on egg shape in guillemots were written in German. Some of them had an English summary, but, as every scientist knows, the summary, or abstract, while purporting to provide an accurate synopsis of the papers content, is often a shop window in which authors make their results seem stronger than they really are.

The first paper, and the source of the conventional wisdom, was that the guillemots pointed egg shape allowed it, not to spin like a top, but to roll in an arc, and it was rolling-in-an-arc that was said to prevent it from falling.

As I read the papers summary and looked at the graphs and tables using a German dictionary to translate their captions I felt that something wasnt right. It didnt add up. I found a German-speaking student in my department and paid him (quite a lot) to translate the paper word for word. The studys conclusions were far from clear, and, as well see, even rolling-in-an-arc was not especially convincing.

I decided to reinvestigate. Although this was an old problem, re-entering the world of guillemot eggs was like exploring a new world, with paths leading in all sorts of new directions in what has since been an exhilarating journey. At one level it sounds trivial who cares why guillemots lay pointed eggs? But at another it was wonderful, encompassing everything that science is supposed to be. And I say that with due modesty. Much of science has been distorted by government-imposed assessment exercises that result in short-term financially motivated studies whose results are often overstated or occasionally even falsified. My egg project had an air of adventure about it and to my mind thats what science should be: an adventure.

One of the first things I discovered was that the guillemots egg and unless I say otherwise, guillemot means the common guillemot was the most popular and sought after for collections. In the past when egg collecting was widespread, without several guillemot eggs your collection was incomplete. Why? Because guillemot eggs are seductively beautiful large, brightly and infinitely variable in colour and pattern, and, as seen on TV, very oddly shaped.

My guillemot research started in 1972 on Skomer Island off the western tip of South Wales and I have been back each year since then. Bounded by 200-foot basalt cliffs, Skomer is one of Britains most important seabird colonies. It enjoys complete protection today but in the past like almost every other British seabird colony Skomers cliffs were plundered for their eggs.

In May 1896 Robert Drane, founding member of the Cardiff Naturalists Society, accompanied Joshua James (J. J.) Neale and his wife and ten children on a trip to Skomer. There are two accounts of their visit: Neales, which is perfectly normal, and Dranes, which is somewhat surreal. Drane entitled his A Pilgrimage to Golgotha but did not reveal where or what Golgotha was, to avoid what we have found to be the detrimental effect to natural history of giving unreserved publicity to the places where the following notes were made. Golgotha is an allusion to Calvary, but literally means the place of skulls, because then as now Skomer is littered with the skulls of seabirds, mainly Manx shearwaters killed by predatory great black-backed gulls. Although the number of skulls and corpses seemed (and still seems) incredible, so too is the breeding population of the nocturnal shearwaters, with current estimates at over 200,000 pairs.

During their visit, two of Neales sons scrambled around the cliffs collecting guillemot and razorbill eggs for Drane. And not without risk. Neale laconically describes how at one point as his eldest boy climbed up from the boat to a group of guillemots, the rock he was holding came away in his hand and he fell backwards, hit the cliff and somersaulted into the sea. It isnt clear how far he fell, but luckily the impact wasnt enough to render him unconscious and he swam to a rock. His brother was close by and managed to haul him into the boat. A day or so later he had recovered from his fall, and as his father commented, it cured him of climbing...

Neale doesnt say where this incident occurred, but there arent that many places you can step from a small boat and climb up Skomers cliffs. My guess is that it must have been at the east end of the island at a place known as Shag Hole Bay where there are still plenty of guillemots, even though the shags that once nested there have gone.

Before that accident, Neales boys had collected a considerable number of eggs that were subsequently blown and added to the many hundreds at Cardiffs natural history museum, which

Drane was certainly not the first to collect guillemot eggs from Skomer. There is a photograph dating from the late 1800s of the owner Vaughan Palmer Daviess daughters and friend all in their twenties blowing guillemots eggs, either for themselves or to give away as souvenirs.

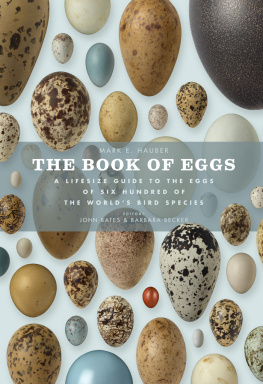

What ends up in private or museum collections are the eggs shells the lifeless, outermost cover of the birds egg. The remainder, the eggs contents that could have contributed to the creation of new life, are either eaten or discarded. Most of us have in our minds two contrasting images of birds eggs. The first is of beautiful, often intricately coloured shells from a diversity of bird species portrayed in books or in museum cabinets. The second is the ubiquitous hens egg either entire in its plastic carton, or as yellow yolk surrounded by its transparent white in a kitchen bowl.