Birds and Us

Birds and Us

A 12,000-Year History from Cave Art to Conservation

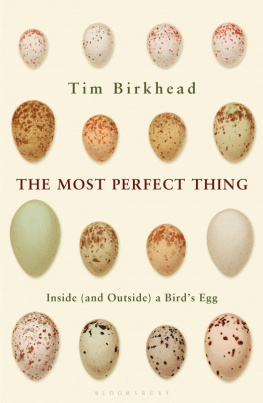

TIM BIRKHEAD

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Text copyright 2022 by Tim Birkhead

The author has asserted his moral rights

The List of Illustrations on constitute an extension of this copyright page

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published in the United States, Canada, and the Philippines by

Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

press.princeton.edu

Original edition first published by Penguin Books Ltd, London in 2022

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-23992-7

ISBN (e-book) 978-0-691-23994-1

Library of Congress Control Number 2022932387

Version 1.0

For my students, undergraduates and graduates, who taught me more than I could ever have anticipated.

Contents

- ix

- xiii

- xvii

- 1

- 20

- 39

- 65

- 95

- 119

- 157

- 192

- 223

- 254

- 278

- 301

- 329

- 339

- 347

- 351

- 385

- 413

List of Illustrations

List of Plates

Preface

At the age of six I was tremendously lucky to have a teacher Mr Govett who was passionate about both birds and art. He read us Arthur Ransomes Great Northern? a story of adventurous children discovering a breeding pair of vanishingly rare Great Northern Divers in the Outer Hebrides. We were then tasked with illustrating scenes from the story. Knowing that I liked birds an interest encouraged by my father Mr Govett asked me to paint the bird itself. I still remember the sense of pride in being selected for this special assignment. Little could he have known how this simple act of encouragement would shape my life.

That experience was reinforced by an extraordinary coincidence. Walking along a desolate beach on the east coast of Scotland a few years later, my father and I came across a Great Northern Diver standing disconsolately on the shoreline. Its crisp black-and-white breeding plumage implied it was in perfect condition, but something was wrong, for it made no attempt to move away. Standing awkwardly, as divers do, the bird looked up at us pitifully, it seemed with its blood-red eyes; it was a victim of oil pollution, which at that time was so common in the worlds oceans. I could not believe that the bird I had painted in Mr Govetts class was here, right in front of me. There was nothing we could do for the unfortunate creature, and when I looked back as we left the shore, it was being chased into the sea by a dog.

These two events, I now realize, sowed the seeds of my life, eliciting a passion for birds, a concern for their welfare, a taste for adventure in wild places and an appreciation of enthusiastic, knowledgeable mentors. Several years on, while in Nova Scotia, waiting for a flight into the High Arctic to study seabirds, I lay in bed at night listening to the haunting cries of Great Northern Divers (or Common Loons, as they are known in North America) echoing eerily across the waters of the nearby lakes.

My performance at school was undistinguished, but an interest in natural history and some lucky breaks allowed me to turn an obsession with birds into a career. This has been a calling that allowed me to recognize the many ways that people connect with birds, from those who feed pigeons in urban parks, or breed birds in aviaries in their back yards, hunt birds for food or fun, or train racing pigeons like elite athletes, to artists who observe and paint birds in evocative ways. There are myriad ways that we can know birds, and that knowledge, whether professional or amateur, scientific or anecdotal, provides us with a deeper understanding of nature itself. The Covid pandemic saw a surge of interest in birdwatching as a physical and psychological escape from the lockdown restrictions. What better evidence is there for the emotional benefits of the natural world, and the need to preserve whats left of it?

Theres a widely used phrase in conservation biology the shifting baseline which bemoans the fact that the current generation has no appreciation for what the natural environment looked like to previous generations, as their only reference is from their own childhood. A shifting baseline is just as applicable to our relationship with birds.

It is all too easy to imagine that our parents generation shared the same concern about the worldwide decline in bird numbers, but they didnt. That awareness of a catastrophic decline in many bird populations became apparent only towards the end of the twentieth century. Looking a generation or two further back still, attitudes towards birds were different, with birds more often being seen as a resource, something to be exploited for meat, feathers, study skins and eggs or simply destroyed because they interfered with human activities.

My aim in this book is to share my enthusiasm for birds and to explain the varied ways that our relationships with them have changed through time. It is a journey that spans several continents and twelve millennia, including my own journey as a bird researcher: from the cave art of our Neolithic ancestors, through the ancient Egyptians bird-filled catacombs of the Nile valley to ancient Greece and Rome and the beginnings of a written history of birds, through the so-called Dark and Middle Ages and a fanatical obsession with falconry to the beginnings of science and a reappraisal of classical knowledge, to the Faroes and a community that for centuries has depended almost entirely on birds, and then to Darwin and the emergence of objective knowledge. We explore the Victorians mania for specimens and the accumulation of bodies of ornithological knowledge as science gained traction. The twentieth century brought us to the beginnings of birdwatching and the field study of birds, triggering an extraordinary flowering of knowledge and empathy for them. Today there is massive, worldwide interest in birds, from the casual Have you heard a cuckoo yet this spring? through to the more scientific, in which novel discoveries, such as those driven by new tracking technologies, have allowed us to see the migratory journeys of cuckoos and other birds in real time.

I have combined my passions for science, art and history to direct a spotlight on the multiple ways of engaging with birds. This historical, wide-ranging approach is the outcome of a lifetime of ornithological research and public engagement that has emerged from an enduring fascination about where our love of birds, and nature as a whole, has come from. By drawing attention to the fact that our present, largely empathetic relationship with birds may be temporary, I hope that we may be better able to protect birds into the future.

Our story starts in southern Spain, in a little-known Neolithic rock shelter in Andalusia. Our early ancestors are not especially renowned for depicting birds in either carvings or cave paintings, as those are few and far between, but here in this one shallow cave there are more bird images than all the other known caves put together. It is a place that for me marks, like no other, the genesis of our relationship with birds.