Ten Thousand Birds

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket art: Magnificent Bird of Paradise , linocut print,

2013 Robert Gillmor

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-15197-7

Library of Congress Control Number 2013939390

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in PF Monumenta and

Verdigris MVB Pro Text

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PREFACE

The body of a bird is not just a prodigiously complicated machine, with its trillions of cellseach one in itself a marvel of miniaturized complexityall conspiring together to make muscle or bone, kidney or brain. Its interlocking parts also conspire to make it good for somethingin the case of most birds, good for flying. An aero-engineer is struck dumb with admiration for the bird as flying machine: its feathered flight-surfaces and ailerons sensitively adjusted in real time by the on-board computer which is the brain; the breast muscles, which are the engines, the ligaments, tendons and lightweight bony struts all exactly suited to the task. And the whole machine is immensely improbable in the sense that, if you randomly shook up the parts over and over again, never in a million years would they fall into the right shape to fly like a swallow, soar like a vulture, or ride the oceanic up-draughts like a wandering albatross.

RICHARD DAWKINS, IN THE WASHINGTON POST ON 23 AUGUST 2011, IN RESPONSE TO TEXAS GOVERNOR PERRYS CLAIM THAT EVOLUTION IS JUST A THEORY

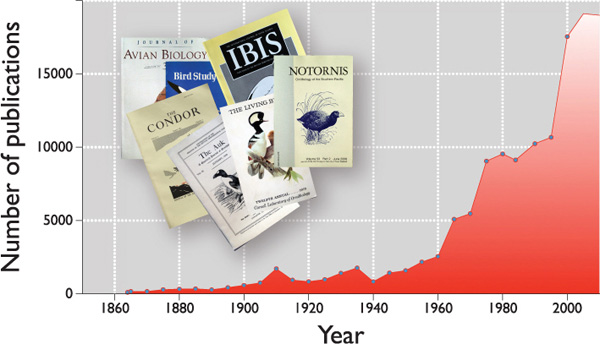

THERE ARE CURRENTLY VERY CLOSE TO TEN thousand species of birds in the world, both beautiful and improbable, and they have contributed more to the study of zoology than almost any other group of animals (Konishi et al. 1989). The reasons are obvious: birds are diurnal, they are often easily observed and studied, and we like them. As a result, the study of birds goes back at least as far as ancient Greece, although it is generally recognized that scientific ornithology began in the mid-1600s with the publication of John Rays Ornithology of Francis Willughby (Ray 1676). Since then, the study of birds has continued apace, with by far the greatest increase in ornithological knowledge occurring since the middle of the twentieth century. We estimate that there have been no fewer than 380,000 ornithological publications since Darwin published The Origin of Species in 1859. The temporal pattern reflects the change in numbers of ornithologists: increasing slowly between 1860 and 1960, but then more rapidly as more academic positions for zoologists became available in the 1960s. In 2011 there were as many papers on birds published as there had been during the entire period between Darwins Origin and 1955.

Several histories of ornithology have been written (appendix 1)especially in the last few years, suggesting that the subject has come of age. Few of these, however, have included the twentieth century, possibly because of the sheer volume of information. Yet residing within this enormous mass of literature is a small number of wonderful, groundbreaking discoveries, and it is these that form the basis for this book. This isnt to say that most of what has been done is of little value but rather that, as in most areas of science, the few individuals that make major breakthroughs have relied consciously or unconsciously on the substantial foundations provided by generations of ornithological foot soldiers.

The number of scientific publications about birds published each year since 1850; data from the Zoological Record and Google Scholar. Inset shows some covers of ornithological journals.

Science in its broadest sense has a long history, but modern science began only in the seventeenth century, with the scientific revolution, as logic and experimentation gradually swept away the folklore, alchemy, and old wives tales that had persisted since the time of Aristotle. As Jrgen Haffer (2007a) points out, the renaissance in science in the mid-1600sand the work of Francis Willughby and John Ray in particularprovided not only a firm scientific foundation for ornithology but initiated what were to become the two major strands in the study of birds: systematics and field ornithology.

The first of these strands, beginning with the naming and description of all known bird specieswhich at the time was thought to number about five hundredformed the basis for Rays Ornithology of Francis Willughby (1676, 1678), so named because Willughby, Rays protg and patron, died at just thirty-six years of age, before their book was completed. Rays second, field-based approach was presented later in his book The Wisdom of God , published in 1691, long after Willughbys death. Here Ray introduced the concept of physicotheology (later known as natural theology), which used the exquisite fit between an animals design and its lifestyle as evidence of Gods wisdom. In modern terms, The Wisdom of God is about adaptation, which for Ray was mediated through God. The book caused a revolution both in religious thinking and in natural history. With extraordinary pre-science Ray asked, for example, why some birds produce a clutch of one egg, while others produce clutches of ten or more; why some birds breed early in the year, while others breed later. Not only did Ray pose important biological questions, he anticipated their answers with uncanny insight and common sense (Birkhead 2008).

Rays ingenious ideas were appropriated by others, most notably William Paley, whose Natural Theology (1802) became essential reading for nineteenth-century Cambridge undergraduates intending to enter the churchas was Darwin before he went off on his Beagle voyage in December 1831. Paleys rich examples captivated Darwin, who went on to call them adaptations. Paley is best known nowthanks to Richard Dawkinss Blind Watchmaker (1986)for his parable of the watch. Imagine finding a watch, he said: its intricate design tells you that it must have a designer. Now look at nature: the exquisite fit between an organism and its environment tells you that it too must have had its designer, and that designer could only have been God. Paleys writings shaped Darwins thinking, not about God but about adaptation, and as he later said, The old argument from design in Nature [natural theology], as given by Paley, which formerly seemed to me so conclusive, fails, now that the law of natural selection has been discovered.

Despite the genius of Rays double-barreled approach, the next two hundred years of ornithology were dominated by systematics: the naming and describing of species, as well as determining their position in Gods grand scheme of things. Only after Darwin seeded the idea that the behavior and ecology of animals might have evolved through natural selection did Rays second idea begin to take hold. But it was a slow change. Until the 1920s, ornithology, like the rest of zoology, consisted almost exclusively of museum workthe study of skins, skeletons, and eggsand the museum ornithologists idea of fieldwork was the killing and collecting of specimens for study. In the late nineteenth century, Elliott Coues (1896) identified the shotgun as the ornithologists most important piece of field equipment. His contemporarieslike Edmund Selous, who opposed museum-based ornithology and attempted to promote the study of the living birdwere castigated. As well see, genuine field ornithology was not reunited with museum ornithology until the period from 1920 to 1940a union that pulled ornithology from the sidelines into mainstream biology (Birkhead 2008). This revolution, which forms an important part of the current book, transformed zoology and fueled the extraordinary explosion in ornithological knowledge.

Next page