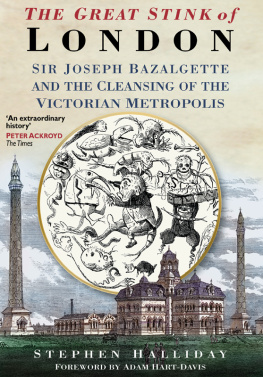

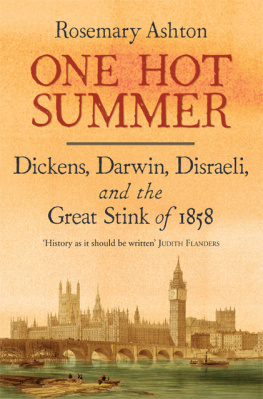

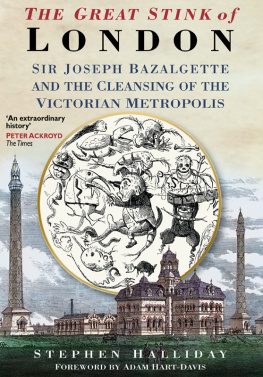

The Great Stink

of London

Sir Joseph Bazalgette and

the Cleansing of the Victorian Metropolis

STEPHEN HALLIDAY

Foreword by

ADAM HART-DAVIS

First published in 1999 by Sutton Publishing

Paperback edition first published in 2001

Reprinted in 2001 (twice), 2002, 2003 (twice), 2006, 2007

Reprinted in 2009 by

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

Stephen Halliday, 2009, 2013

The right of Stephen Halliday, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9378 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

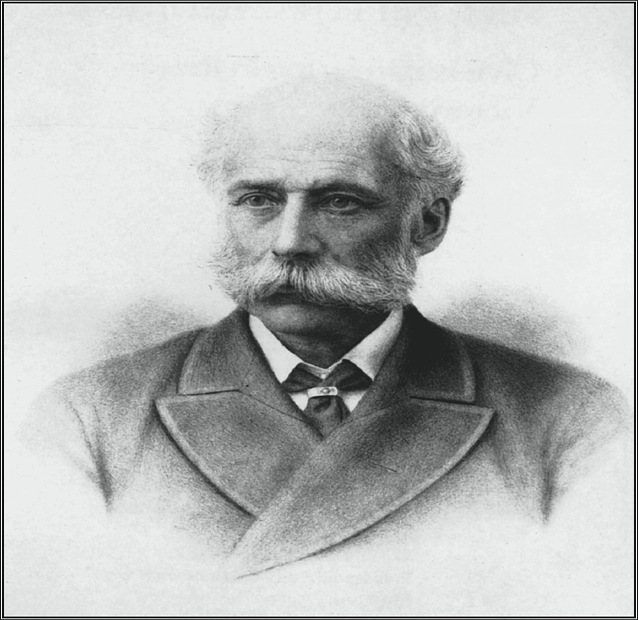

Sir Joseph Bazalgette, about 1880; from a picture in the possession of Rear-Admiral Derek Bazalgette, CB. (Derek Bazalgette)

Acknowledgements

Writing this book has been, for me, a labour of love but in the process I have incurred many debts. First, my family: my wife Jane, my daughter Faye and son Simon have tolerated, without complaint, my frequent references to Victorian waste disposal arrangements, often in front of their friends. The same is true of my colleagues, particularly the two who share my office, Jane Fletcher and Christiane Hermann-Duthie, who for over a year allowed me to decorate the walls with pictures of Victorian sewers and their contents. Christiane also found for me, and translated, information about the life and work of Justus von Liebig and Robert Koch which would otherwise have been inaccessible to me. Joyce Speller typed up the notes from which the book was written, learning more than she ever expected or wanted to learn about Victorian sewage.

My employers, Buckinghamshire Business School, allowed me the time to do the research and the staff at Guildhall Library, the Metropolitan Archives, the British Newspaper Library at Colindale, the Wellcome Trust and the Institution of Civil Engineers demonstrated the tact and patience which is a necessary quality of librarians who are required to deal with hapless and technologically incompetent academics. One hardly ever learns the names of librarians but two that I came to know well were Michael Chrimes and Carol Arrowsmith at the Institution of Civil Engineers, where they take good care of Sir Joseph Bazalgettes archive material. Regrettably this does not include a diary or other personal papers, a fact which may be attributable to the sheer volume of professional work that left him, in the words of his great-grandson Rear Admiral Derek Bazalgette, time only to produce children and work on London.I have been privileged to meet many of Sir Josephs descendants who have given me all the help and encouragement I could have wished in completing this work, particularly his great-grandson Paul Bazalgette, whose exertions have been well beyond the call of duty. Thames Water PLC, who now operate the system that Sir Joseph built, have a fine collection of contemporary illustrations which they kindly made available to me and it is through the generosity of the company chairman, Sir Robert Clarke, that the colour illustrations have been included. I am especially indebted to Robin Winters who spent many hours on my behalf searching the companys archives at Abbey Mills.

Bazalgette had time only to produce children and work on London

Finally, I acknowledge the help and encouragement given to me in the early stages of the research by my good friend the distinguished engineer Dr Edmund Hambly. In 1994 he was elected President of the Institution of Civil Engineers, an office that Sir Joseph Bazalgette himself held in 18834. Edmunds unexpected and untimely death in March 1995, only four months into his Presidency, deprived the world of an individual whose distinction as an engineer was outweighed only by his qualities as a man. He is greatly missed by his family and by his many friends.

To his memory this work is dedicated.

Stephen Halliday, 1998

Sir Joseph and Lady Bazalgette had ten children. Derek Bazalgettes comment was recorded in the Newcomen Societys Transactions, vol. 58, 19867.

Foreword

by Adam Hart-Davis

Throughout human history, the number one cause of death has been contamination of water supplies. During the 1830s the infant mortality rate in British towns was close to 50 per cent; that is, of all the babies who were born, only half reached their fifth birthdays. The unlucky ones died of diarrhoea, dysentery, typhoid, and the newly imported and horrifying disease cholera but basically they died because the sewage was not separated from the drinking water, so that one person infected with cholera could easily start an epidemic. This is still a major cause of death in some parts of the developing world, but in England we no longer have a problem. Why? Because of the sewers built against much political and other resistance by Joseph Bazalgette.

By 1850 the rapidly expanding population of London had reached two million. As Stephen Halliday describes in graphic detail, the sewage overflowed and leaked from the limited number of cesspools, and seeped through inadequate sewers into the Thames, where it slopped up and down with the tides, slowly decomposing on the gently sloping mud banks. Matters came to a head in the long hot summer of 1858, when the great stink resulting from this rotting sewage was debated in Parliament, where it got right up the noses of the Members, who could no longer ignore the pestilent filth.

After a careful account of the labyrinthine complexities of the political red tape that had to be cut, this book tells the dramatic intertwined stories of the Great Stink, the dreaded cholera and the arguments about what caused it, the construction of the Victoria, Albert, and Chelsea embankments, and above all how the sewers were built and cholera epidemics eliminated from London.

For thirty-three years Joseph Bazalgette was Chief Engineer to the Metropolitan Board of Works. His primary and most important task was to design and build the great system of intercepting sewers which have ever since taken Londons sewage away from the city, but in order to do this he also had to construct the vast embankments, which reclaimed more than 50 acres of land from the river and provided accommodation not only for his low-level sewers but also for underground trains and other services, and roads and parks on the surface. Bazalgette built or restored several of the major bridges across the river, and also laid out some of the great roads in the metropolis, including Shaftesbury Avenue and Charing Cross Road, not to mention Battersea Park, Clapham Common, and various other parks. The shape of London as we know it today owes much to his design and foresight.

I enjoyed all the technical information, and was particularly intrigued to find out how Bazalgette championed the use of the newfangled Portland Cement, set up rigorous tests for quality control, and eventually used it without bricks for miles of sewers.