Table of Contents

The Modern

Weird Tale

S.T. Joshi

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina, and London

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Joshi, S.T., 1958

The modern weird tale / by S.T. Joshi.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-7864-0986-X

1. Horror tales, AmericanHistory and criticism. 2. American fiction20th centuryHistory and criticism. 3. English fiction20th centuryHistory and criticism. 4. Horror tales, EnglishHistory and criticism. I. Title.

PS374.H67J67 2001

813.0873809dc21 00-54805

CIP

British Library cataloguing data are available

2001 S.T. Joshi. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover: 2001 Index Stock

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To Stefan R. Dziemianowicz

Preface

This book is an informal follow-up to The Weird Tale (1990), in which I discussed six writers of the Golden Age of the horror tale (roughly 18801940). No reference to that earlier volume is, however, necessary in understanding this one. Probably the most vexing problem I have faced is to decide which authors of postWorld War II weird fictionespecially the authors of the horror boom of the 1970s and 1980s, many of whom retain a popular following to the present dayshould be covered in this study. I do not know if I have evolved any very coherent rationale for the inclusion or exclusion of a given writer; in some cases I will admit frankly that I have written about certain authors simply because Ihappen to like them. I hope that I have in general covered those weird writers who are either unavoidable on purely literary grounds or because of their prominence in the field; the two groups, obviously, are not identical. My discussions generally cover works published prior to 1994.

In the course of my work on this book I have considered (or had suggested to me) such authors as Iain Banks, Charles Beaumont, L. P. Davies, Les Daniels, Dennis Etchison, Charles L. Grant, James Herbert, K. W. Jeter, Robert R. McCammon, Richard Matheson, David J. Schow, Rod Serling, Dan Simmons, Steve Rasnic Tem, Thomas Tessier, Chet Williamson, and a number of others. My reasons for excluding these authors are very complex and are not to be taken as judgments on their literary work. I particularly regret that, although I have attempted to probe the relationship between the weird tale and the mystery story in such writers as Robert Bloch and Thomas Harris, I have been unable to explore the very involved interplay between weird and science fiction, especially as represented in the two pioneering writers in this mode, Fritz Leiber and Ray Bradbury. Their work is so voluminous and complex as to be impervious to brief analysis, and it seems to me that my book is already large enough.

My method of citation of works is, in the interests of space, very condensed. I have assigned abbreviations to all important primary works and some secondary works I discuss; these abbreviations can be found in the bibliography at the rear of the volume (an asterisk indicates the edition I have used if it is not the first). In the text, therefore, I cite these works only by abbreviation and page number. My bibliography should not in every instance be considered complete; rather, it lists only those works by and about the author I have consulted for this volume. Save where indicated, however, I have attempted to read all the weird work of the authors I cover.

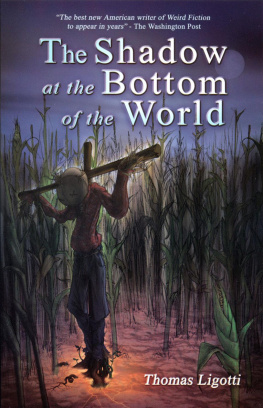

It is my pleasure to thank the many associates who have assisted me in the writing of this book. I could write an entire essay on the help provided by Stefan R. Dziemianowiczin the supplying of texts, in suggestions for arrangement, in guidance on individual authors, and in many other less tangible waysand if this book does nothing more than to encourage him to write his own study, I shall be content. Other individuals such as Lance Arney, Scott D. Briggs, Rusty Burke, Richard Fumosa, Sam Gafford, Jay Gregory, Anna Magee, Steven J. Mariconda, Marc A. Michaud, and Darrell Schweitzer have helped in various ways. I am especially grateful to Ramsey Campbell, T. E. D. Klein, and Thomas Ligotti for reading my chapters on their work and making highly illuminating comments. It is difficult to write about living authors, especially if one is acquainted with them, and I hope that my objectivity has not suffered in these or other instances.

I am aware that some, or much, of this book is deliberately controversial or polemical; but I hope it is evident that I have not come to my views carelessly and that my intent in expressing them is simply the utterance of the truth as I see it (insofar as there can be truth in such matters). I may well be wrong, but I would be reluctant to acknowledge that I am malicious. Criticism is not an exact science, and the expression of an informed judgment is my only goal and purpose.

S. T. J.

Introduction

During the early part of the twentieth century, weird fiction was not so much a genre as the consequence of a world view, and relatively few authors of what could only retrospectively be called weird fiction were conscious of writing in a specifically weird mode that was to be radically distinguished from mainstream writing. H. P. Lovecraft (18901937) is in many ways a watershed here: not only was he (because of his early interest in and publication by the American pulp magazines) the first significant writer who understood that his work was weird, and who for various reasons was repeatedly rebuffed by mainstream publishers, he was perhaps also the last writer whose weird fiction was the systematic embodiment of a world view.

Weird writing has certainly proliferated since Lovecrafts time, and especially since about 1970, but it is not at all clear that much of this mass of writing has any literary significance or much chance of survival. Indeed, there appears to be a consensus among informed critics that the amount of meritorious weird fiction being written today is in exactly inverse proportion to its quantity. One can only ask: what happened?

The query should be interpreted not merely to the causes for the decline in the quality of weird writing just as it is (or was) becoming a spectacularly marketable phenomenon, but to why and how weird fiction became concretized into a definite genre. The answer to this second question may help us to answer the first. By genre I mean a certain body of conventionalized scenarios and tropes from which authors can draw and upon which they can, as it were, hang a tale in a formulaic way, since these scenarios and tropes have become so common and readily comprehensible to readers that their mere citation triggers certain stock responses and situates the work in an easily identifiable class. Such tropes, in weird fiction, include the vampire, the ghost, the reanimated corpse, the haunted house, and the like. They were, certainly, already well used by the late Victorian period, and Lovecraft himself felt that many of them were so stale that they ought to be avoided entirely or utilized in some distinctive manner so as to lend them freshness and vigor. His general solution was to transfer the locus of fear from the mundane to what he called the Great Outsidethe illimitable voids of outer space. As a result, he effected a remarkable union between weird fiction and the emerging mode of science fiction. But few have followed in his footstepseither because he did what he did so well and so completely, or because it was felt that this sort of cosmic horror was best left to Lovecrafts generally mediocre and unimaginative disciples and imitators.