The Apes Wife and Other Stories Copyright 2013 by Caitln R. Kiernan. All rights reserved.

Dust jacket illustration Copyright 2013 by Vincent Chong.

All rights reserved.

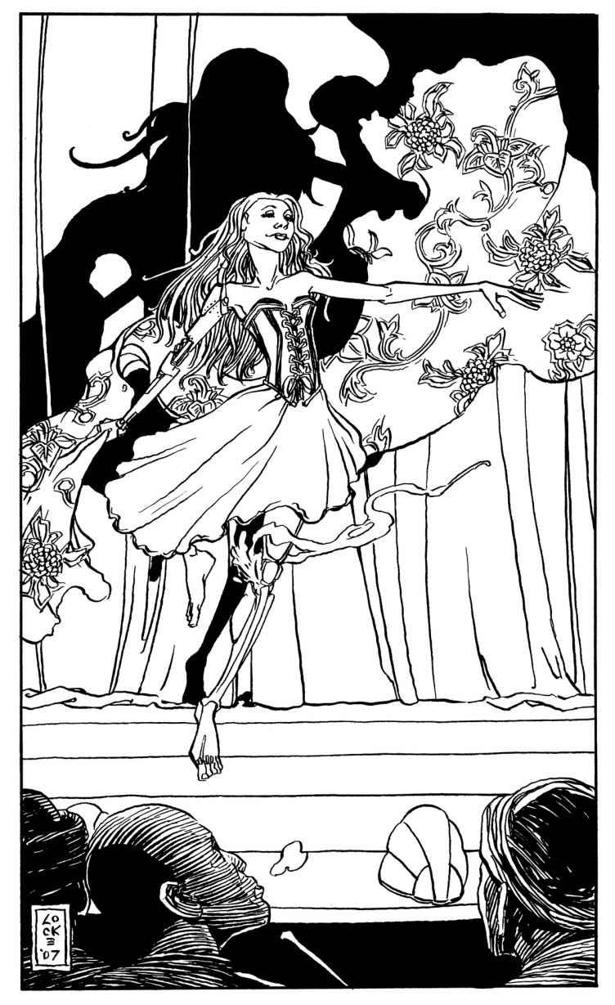

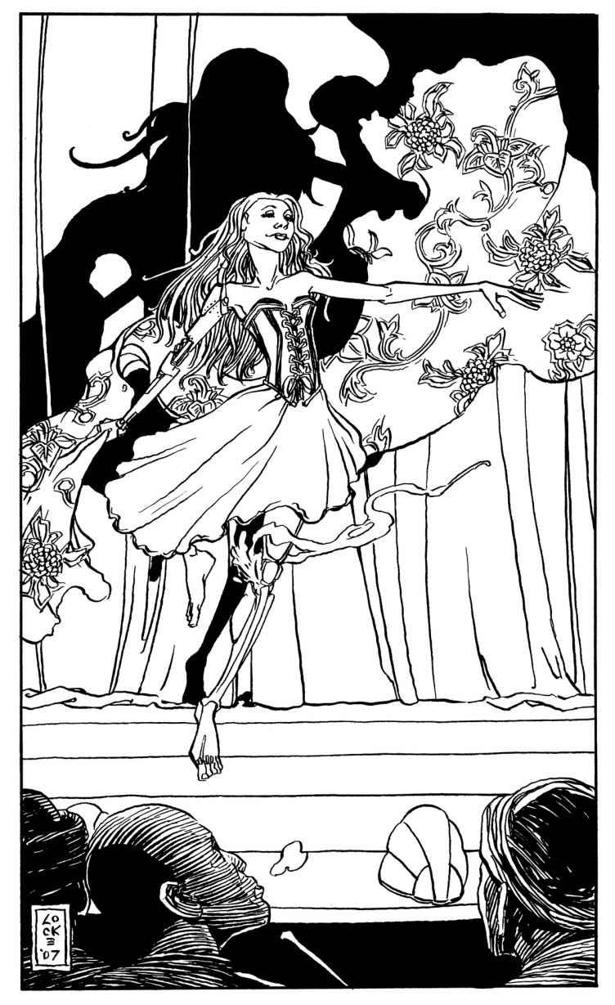

Interior illustrations Copyright 2013 by Vince Locke.

All rights reserved.

Print Interior design Copyright 2013

by Desert Isle Design, LLC. All rights reserved.

First Edition

ISBN

978-1-59606-587-1

Subterranean Press

PO Box 190106

Burton, MI 48519

subterraneanpress.com

www.caitlinkiernan.com

greygirlbeast.livejournal.com

Twitter: @auntbeast

For Michael Zulli

I talk about the gods, I am an atheist. But I am an artist too, and therefore a liar. Distrust everything I say. I am telling the truth.

Ursula K. LeGuin,

Introduction to The Left Hand of Darkness (1976)

Table of Contents

Introduction

I.

Ive never been much for one-note short story collections, dominated by any single sort of tale. As a kid, my favorite collections generally were those that displayed diversity, in mood and subject matter. These are among the books I grew up reading and read as a teen. For example, Ray Bradburys A Medicine for Melancholy (1958) and Angela Carters Fireworks: Nine Profane Pieces (1974). Shirley Jacksons The Lottery and Other Stories (1949), and Harlan Ellisons The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World (1969). The collected works of Ambrose Bierce and, H. P. Lovecraft, who was more capable of whimsy and Dunsanian fancies than most realize. When I sat down to compile this volume, looking back over my earlier and somewhat themed collections, I determined this book would, instead, present a wide range of the fantastic, a collection that wanders about Colonial New England cemeteries, then sets off for Mars. That is content, one page, with werewolvery and ghosts, then a few pages later its busy with steam-driven cyborgs in the Wild West, before careening into a feminist/queer retelling of Beowulf, just prior to landing amid the intrigues of a demonic brothel in a 1945 Manhattan that wont be found in any history book.

I cannot help but feel that publishing, over the past several decades, has become more than ever determined to drive authors to specialize, rather than encouraging them explore and develop their potential range. This, in turn, trickles down to readers, who can become as hidebound as authors. Which is a loss, I think, for readers and for writers. Why would anyone wants to know 101 ways to prepare meatloaf, when they have an infinite variety of delicacies at their fingertips? We are what we cook, and what we eat, and, too, we are most certainly what we write and read.

II.

Back in July, during Readercon 23, Peter Straub and I were interviewed by Gary Wolfe and Jonathan Strahan. At some point during the interview, I was asked how and why Im so prolific. The why part, thats simple. Because I havent much choice. A working author who isnt a bestseller works (or is otherwise employed, or independently wealthy) and works nonstop, usually seven days a week, or the bills arent paid. As to the how, that, I suppose comes by learning to ignore the exhaustion, the stress, illness, the routine that can become a grinding tedium no matter how much I might like what Im doing. By learning that days off and vacations are only very rarely an option. Addictions help. As do insomnia and a deep well of ideas and characters, one that I live in constant fear of running dry.

The story from which this books title takes its name was written and published in 2007. Since then, Ive written (and sold) about one hundred short stories and novellas. Fourteen of them are collected herein. I believe theyre thirteen of the best of the lot. I hope you will agree.

Caitln R. Kiernan

17 December 2012

Providence, Rhode Island

The Steam Dancer (1896)

Missouri Banks lives in the great smoky city at the edge of the mountains, here where the endless yellow prairie laps gently with grassy waves and locust tides at the exposed bones of the world jutting suddenly up towards the western sky. She was not born here, but came to the city long ago, when she was still only a small child and her father traveled from town to town in one of Edisons electric wagons selling his herbs and medicinals, his stinking poultices and elixirs. This is the city where her mother grew suddenly ill with miners fever, and where all her fathers liniments and ministrations could not restore his wifes failing health or spare her life. In his grief, he drank a vial of either antimony or arsenic a few days after the funeral, leaving his only daughter and only child to fend for herself. And so, she grew up here, an orphan, one of a thousand or so dispossessed urchins with sooty bare feet and sooty faces, filching coal with sooty hands to stay warm in winter, clothed in rags, and eating what could be found in trash barrels and what could be begged or stolen.

But these things are only her past, and she has a bit of paper torn from a lending-library book of old plays which reads Whats past is prologue, which she tacked up on the wall near her dressing mirror in the room she shares with the mechanic. Whenever the weight of Missouris past begins to press in upon her, she reads those words aloud to herself, once or twice or however many times is required, and usually it makes her feel at least a little better. It has been years since she was alone and on the streets. She has the mechanic, and he loves her, and most of the time she believes that she loves him, as well.

He found her when she was nineteen, living in a shanty on the edge of the colliers slum, hiding away in among the spoil piles and the rusting ruin of junked steam shovels and hydraulic pumps and bent bore-drill heads. He was out looking for salvage, and salvage is what he found, finding her when he lifted a broad sheet of corrugated tin, uncovering the squalid burrow where she lay slowly dying on a filthy mattress. Shed been badly bitten during a swarm of red-bellied bloatflies, and now the hungry white maggots were doing their work. It was not an uncommon fate for the likes of Missouri Banks, those caught out in the open during the spring swarms, those without safe houses to hide inside until the voracious flies had come and gone, moving on to bedevil other towns and cities and farms. By the time the mechanic chanced upon her, Missouris left leg, along with her right hand and forearm, was gangrenous, seething with the larvae. Her left eye was a pulpy, painful boil, and he carried her to the charity hospital on Arapahoe where he paid the surgeons who meticulously picked out the parasites and sliced away the rotten flesh and finally performed the necessary amputations. Afterwards, the mechanic nursed her back to health, and when she was well enough, he fashioned for her a new leg and a new arm. The eye was entirely beyond his expertise, but he knew a Chinaman in San Francisco who did nothing but eyes and ears, and it happened that the Chinaman owed the mechanic a favour. And in this way was Missouri Banks made whole again, after a fashion, and the mechanic took her as his lover and then as his wife, and they found a better, roomier room in an upscale boarding house near the Seventh Avenue irrigation works.

And today, which is the seventh day of July, she settles onto the little bench in front of the dressing-table mirror and reads aloud to herself the shred of paper.

Whats past is prologue, she says, and then sits looking at her face and the artificial eye and listening to the oppressive drone of cicadas outside the open window. The mechanic has promised that someday he will read her The Tempest by William Shakespeare, which he says is where the line was taken from. She can read it herself, shes told him, because she isnt illiterate. But the truth is shed much prefer to hear him read, breathing out the words in his rough, soothing voice, and often he does read to her in the evenings.