For Eileen

CONTENTS

PREFACE

What happens when a paradigm shifts? Do we simply wake up one day and realize that the past seems irreversibly quaint? Or do financial institutions fail, governments topple, industries break down, and cultures crack in two, with one half pushing to go forward and the other half pulling back?

This is a book about personal mastery in a time of radical change. As we address our increasing problems with increasing collaboration, were finding that we still need something morethe bracing catalyst of individual genius.

Unfortunately, our educational system has all but ruled out genius. Instead of teaching us to create, its taught us to copy, memorize, obey, and keep score. Pretty much the same qualities we look for in machines. And now the machines are taking our jobs.

I wrote this book to cut cubes out of clouds, put our swirl of societal problems into some semblance of perspective, and suggest a new set of skills to address them. While the problems we face today can be a source of hand-wringing, they can also be a source of energy. They can either lead to societal gridlock or the most spectacular explosion of creativity in human history.

One things for sure: Theres no going back, no secret exit, no chance of stopping the clock. The only way out is forward. Our best hope is that once we see the shape of our situation, we can turn our united attention to reshaping it. It wont require a top-down strategy or an international fiat to get the transformation going. Just a relative handful of peoplemaybe people like youwith talent, vision, and a few modest tools.

Ive divided the book into seven parts. The first is about the mandate for change. The next five are the metaskills youll need to make a difference in the postindustrial workplace, including feeling , seeing , dreaming , making , and learning . The last is a set of suggestions for educational reform, written from the perspective of a hopeful observer.

As you read about the metaskills, take comfort in the knowledge that no one needs to be strong in all five. It only takes one or two talents to create a genius.

Marty Neumeier

PROLOGUE

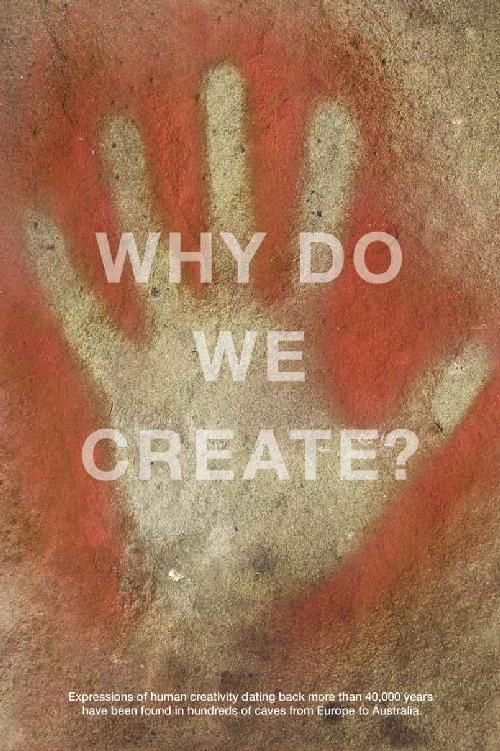

The Midi-Pyrnes, southern France. A spray-painted silhouette of a prehistoric hand, positioned low on the wall at Pech Merle, seems at odds with the other images in the cavethe fluidly stylized drawings of horses, mammoths, reindeer, and other herd animals of the prehistoric hunt. In fact, the hand stencils are the only naturalistic references to human beings at all, and the only subjects of any kind shown actual size. You could place your own hand over the stenciled hand of a cave painter, and even after 25,000 years of human evolution, your hand would fit.

The stencils are highly mysterious. Why would artists with enough skill to conjure magnificent animals in full motion, and who entered the caves to make paintings only after practicing outside the caves, bother to tag the wall with a simple stencil that a kindergartener could make on the first try? Were the hands the equivalent of personal signatures, or perhaps clan symbols? Or were they examples of ancient graffiti, painted by nonartists after the real artists had left? Why were there no images of human beings drawn in the same style? And what exactly were the cave paintings for?

No one can say for sure, but heres a theory that fits the facts: The paintings were designed as a kind of magical mystery show to inspire greatness in the hunt. The caverns were prehistoric cathedrals, special places of elevated consciousness where the hunters could psych themselves for the coming hunt. Animals, not humans, were the subjects, because animals were what the hunters revered. They respected their immense power and beauty in a world where humans were lower on the food chain.

When Pablo Picasso came to view the caves of southern France, he couldnt help notice a particular nuance. The ancient artists had deftly arranged their two-dimensional images over the natural bumps and fissures of the stone, giving them a subtle depth. When viewed in the flickering light of a candle, voil! the dimensionalized animals came to life, appearing to fly across the walls. The caves, in this construction of the facts, were nothing less than the ancient version of our 3D cinemas. On a good night (or with the right drugs) they were probably much better than our 3D cinemas.

And the hand silhouettes? Poignant symbols of gratitude for a unique and surprising gift. No other animal of their acquaintance could fashion tools, hunt with weapons, or cast motion pictures onto cave walls. The human hand, with its sensitive fingers and opposable thumb, made all this possible. So for about ten thousand years our ancestors enshrined their thanksgiving in hundreds of caves, from Africa to Australia, to remind us of who we are and where we came from. Theyre reaching out as if to say: This hand made this drawing.

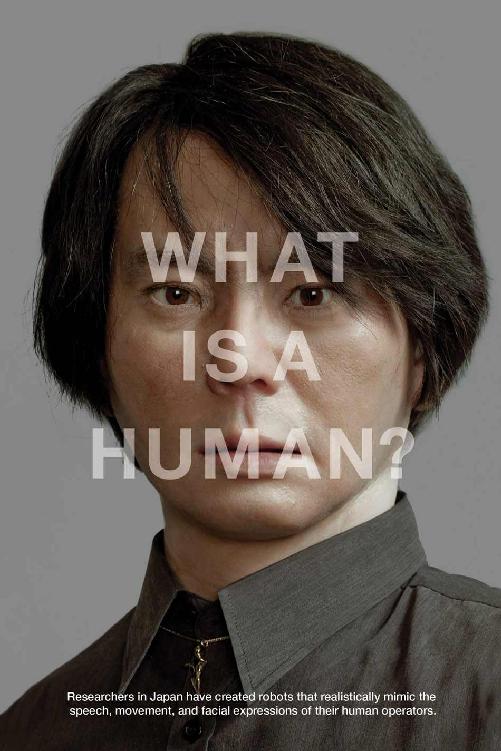

8.7 million homes, North America. Its a poor workman who blames these was the clue that Alex Trebek read from the television monitor. It was February 16, 2011 , in the very last round of a three-day Jeopardy! marathon that pitted IBMS Watson computer against two human champions, Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter. Ken was the biggest money winner of all time. Brad held the record for the longest winning streak. To rack up a score, a contestant must be the first to hit the buzzer with the right answer, or more precisely, the right question, since the game begins with the answer.

Even before Alex finished reading the clue, Watsons 2,880 parallel processor cores had begun to divvy up the workload. Who or what is workman? What does poor mean in this context? Is workman penniless? Maybe out of a job? Meanwhile, other processors got busy parsing the sentence. Which word is the subject? Which is the verb? If this word is a noun, is it a person or a group? Making the task more tricky, Jeopardy! clues are displayed in all capital letters, so Watson had to figure out if WORKMAN was a proper noun or a common noun.

Despite knowing almost nothing, at least in the human sense of knowing, Watsons massively parallel processing system held a distinct advantage over its human counterpart. It was fast. At billion operations per second, it could search gigabytes of data, or the equivalent of one million books, in the blink of an eye. It could also hit the buzzer in less than eight milliseconds, much faster than a human hand.

Yet Watson was programmed not to hit the buzzer unless it had a confidence level of at least percent. To reach that level, various algorithms working across multiple processors returned hundreds of hypothetical answers. Another batch of processors checked and rechecked these answers against the stored data, assigning probabilities for correctness. During the three seconds that these operations took, Watsons onstage avatar, a color-shifting globe with expressive lines fluttering across its face, gave the distinct impression of someone thinking deeply.

Then the buzzer.

What are tools? answered Watson in a cheerful computer voice. The confidence rankings for the top candidates had been tools at percent, Yogi Berra at percent, and explorer at percent. So tools it was.

You are right for $2,000 , said Alex.

By the end of the game Watson had passed Kens $19,200 and Brads $21,600 to win with $41,413 , becoming the first nonhuman champion of Jeopardy!

Below Kens written answer to the Final Jeopardy question he had scrawled the footnote: I, for one, welcome our new computer overlords.

Next page