Grove - One-on-one with Andy Grove : how to manage your boss, yourself, and your coworkers

Here you can read online Grove - One-on-one with Andy Grove : how to manage your boss, yourself, and your coworkers full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York, year: 1987, publisher: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, genre: Business. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

One-on-one with Andy Grove : how to manage your boss, yourself, and your coworkers: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "One-on-one with Andy Grove : how to manage your boss, yourself, and your coworkers" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Grove: author's other books

Who wrote One-on-one with Andy Grove : how to manage your boss, yourself, and your coworkers? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

One-on-one with Andy Grove : how to manage your boss, yourself, and your coworkers — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "One-on-one with Andy Grove : how to manage your boss, yourself, and your coworkers" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

THANKS...

... are due to the editors of the San Jose Mercury News, who recognized that there are many people out there with questions about how to manage at the workplace. Thanks also to readers of that newspaper and others elsewhere in the U.S. who thought that I might have answers.

I am grateful to Karen Thorpe for helping me with the seemingly never-ending task of putting this book together, always maintaining an even temper, even when I lost mine. But, most of all, I am indebted to my wife, Eva. Through countless "one-on-ones," she did her best to make sure that my advice was practical, my prose readable, and that I dealt with the questions that were posed and not the ones I wished had been. There probably has never been a muse more constructively critical of her subject!

Everybody Is a Manager!

I have been a manager for over twenty years. I've managed small groups and big departments. I had successes and I had failures. I enjoyed myself, and I fretted. I taught hundreds of coworkers and I also learned much from them.

As president of Intel Corporation, a microchip manufacturer employing over 18,000 people around the world, I am often asked to speak on the subject of managing. My talks are usually followed by a question-and-answer session, after which people also come up to ask my opinion about problems they have at work. The great variety of such problems intrigued me, and so when the San Jose Mercury News offered me the opportunity to write a weekly question-and-answer column on the subject of managing, I jumped at the chance.

Writing the column exposed me to an even broader range of work problems. People who would never think of attending my talks wrote and solicited my advice or reaction to situations they faced at work. All kinds of people wrote: store clerks, owners of small companies, college students, department managers at large organizationspeople from just about every conceivable work situation.

As I kept reading and answering questions from the work-lorn and the work-worn, I couldn't overlook the fact that the overwhelming majority of writers asked for help with interpersonal relationships at work. People wanted ideas on how to deal with the boss who never gives feedback, with the employee who doesn't care about her work, with the customer who propositions them, with coworkers who steal or who crack their gum loudly. In other words, people wanted ideas on how to manage better at their workplace: manage as in "the boss manages his employees," and also manage as in "make do" or "get along."

I decided that there was a real need for a book about managing that addressed both meanings. As I see it, everybody is a manager. The oldest and most frequently used definition of the word is "getting things done through other people." Getting along at the work place also requires exactly that: getting things done yourself or through your employees, your peers, and most important of all, your own boss. So, everybody who works is indeed a manager whether or not he or she holds that title.

Twenty-some years ago I would not have thought I'd ever find myself in a position of giving such advice. I certainly didn't start my career with any notions of ever becoming a manager in any sense of the word. When I was in my early twenties, a close friend asked if I wanted to get into management. I looked at him in amazement, wondering if he had lost his marbles, and answered that I just couldn't see wasting my time that way. So, how did it all happen? As I now look back, I realize that there were several incidents that, each in their own way, nudged me to where I am today.

The first took place in Hungary, where I was born. I was four- teen years old and I aspired to become a journalist. I wrote with ease, enjoyed it, and was a reporter for the youth newspaper. Like everything else in Communist Hungary, this paper was under the influence of the regime. I wrote about nonpolitical student concerns, like going back to school after summer vacation, making friends, and the like. Most everything I wrote was published in the paper, and I was enthusiastic and happy.

Some time later, a relative fell into disfavor and was imprisoned without trialnot an uncommon occurrence in Hungary during those years. After that none of my articles saw print. Being a naive kid, I didn't see the connection between these two events for quite a while. Later it dawned on me that I was also getting a cold shoulder from the people who ran the newspaper. Not only did they not print my pieces, they even stopped talking to me.

I was as crushed as only a slighted adolescent can be. Eventually my depression gave way to the determination never to find myself in that kind of a situation again. I did not want a profession in which a totally subjective evaluation, easily colored by political considerations, could decide the merits of my work. I ran from writing to science.

Next, a very special night on a train comes to mind. It was taking several hundred Hungarian refugees, myself included, who had left the country in the aftermath of the 1956 uprising from Vienna to the German port city of Bremerhaven. There a ship bound for the U.S. was waiting for us. On the train I stared out the window at the dark countryside racing by, deep in thought. The reality of leaving the country of my birth for a faraway and unknown land was sinking into my twenty-year-old consciousness. Even as I was enveloped by the fear of the many unknowns in my future, I began to realize that I would no longer have to pretend to believe in things that I detested just to get by.

I settled in New York and started to study engineering at the City College of New York. In my first year, as a refugee, I received a scholarship. When it ran out, I sought help from the chairman of my department. He was a crusty old guy; even macho seniors trembled at the sight of him. I sat in his office, need having overcome my hesitancy to approach him. He looked at me with those famous piercing eyes as I told him my hard-luck story. Hungarian refugees were still in the news, and frankly I hoped that would help me get another scholarship.

The piercing eyes waited until I finished my story. Then he asked how much I needed to live on. I told him. He whipped out the longest slide rule I have ever seen, calculated for a while, and looked at me again. He asked, "How about working for it, young man? You could earn what you need in twenty hours of work a week. It will do you good." So I ended up working for crusty Professor Schmidt, running his copies and his errands, typing with two fingers, filing, whateverand supported myself through my remaining years of college that way. It did do me good, in more ways than one. Day in and day out I was exposed to Professor Schmidt's blunt, no-nonsense, results-oriented yet caring personality. I like to think that some of it rubbed off on me.

A few years later, armed with a Ph.D., I started work at Fairchild Semiconductor, the then-leading Silicon Valley chip-research laboratory. I was a member of a small research group. My assignment was to come up with explanationstheories, if you likethat made sense out of the experimental findings of my coworkers. Once such theories existed, they would provide ideas for other experiments. As the "theorist" of our group, I found myself giving direction to my colleagues. I wasn't their boss, yet I influenced their work and activities. Later I was promoted and became the head of this same group. Now I could give direction by virtue of my new position. Yet there was no change in the relationship between me and the other members of the group. I discovered that it was "knowledge power" more than "position power" that enabled me to influence the activities of others, to manage.

There is a real distinction between the two, and this became even clearer to me in the early days of Intel. Here I started out with a nice sounding title-director of operations. The trouble was, I knew very little about the work some of my subordinates were doing. One was a manufacturing expert, another a computer-memory designer. In my previous research position I had no exposure to either field. Even so, I was, in name at least, responsible for their work. What to do? Simple. I arranged for "private lessons" with each. Several times a week I sat down with one or the other, notepaper in hand, and got on with my next lesson in manufacturing or memory design. After a long series of lessons, I became conversant enough to listen to them more intelligently and gradually even to offer some reasonable suggestions. Another key lesson in my development as a manager had taken place: the importance of learning from one's employees.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

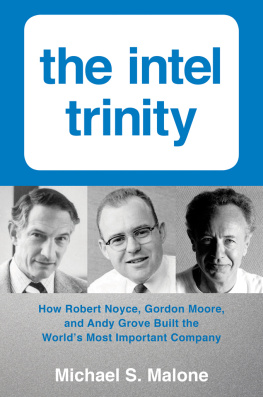

Similar books «One-on-one with Andy Grove : how to manage your boss, yourself, and your coworkers»

Look at similar books to One-on-one with Andy Grove : how to manage your boss, yourself, and your coworkers. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book One-on-one with Andy Grove : how to manage your boss, yourself, and your coworkers and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.