JOHN C.ESPOSITO

To Linda and Nick, the flames in my heart

To firefighters and fire prevention professionals

Injustice is relatively easy to bear;

what stings is justice.

H.L.Mencken

I owe debts of gratitude to a number of people who provided encouragement and assistance in the writing of this story

First, my agent, Albert Zuckerman at Writers House, provided invariably shrewd advice about the structure of the book as well as about the publishing industry.

Among the people in Boston, Fire Commissioner Paul Christian, who opened his department's records of the Grove fire to me, helped immeasurably. Firefighter William Noonan, who has made the fire his special province, assisted me in wading through his vast archive of transcripts, news clippings, and photographs. Throughout the writing of this book, Bill promptly answered every email inquiry for clarification of some fine points.

William Arthur Reilly, son of the fire commissioner at the time of the fire, was generous with his time and provided invaluable insights about his father. I have made some stern judgments about the senior Mr. Reilly, but I hope that my essential respect for his performance after the fire is evident.

Dick Dray, Mr. Reilly's friend, was unfailingly generous with his time and contacts.

Author and Boston Herald reporter Stephanie Schorow, who has written extensively and well about the Grove and other Boston fires, provided helpful advice and materials.

I am indebted to several long-time friends for their support during the early lonely days: Daniel Weiss, Kay Gelfman, Bob Henzler, Larry J.Silverman, Mark Adams, and Eric Bruce. I thank Anna La Violette for her boundless enthusiasm and Susan La Violette for her kindness. My special thanks go to Jamie Rosenthal Wolf for her unremitting interest and keen insights.

David Martinez created the Cocoanut Grove graphic that I believe is so helpful in understanding the club's layout.

Alison Sundet provided timely help with research.

Although I have never met him, I am grateful to Jack Beatty, author of The Rascal King (Da Capo Press, 2000). His excellent biography of James Michael Curley was a primary source of information about that political legend. In addition, I would recommend Barbara Ravage's Burn Unit (Da Capo Press, 2004) to readers interested in the development of modern treatment of bum injuries.

The capable staff at Da Capo Press has made the production of this book trouble-free: John Radziewicz, Kevin Hanover, Kate Adams, Sean Maher, Fred Francis, Erin Sprague, Matty Goldberg, Liz Tzetzo, Alex Camlin, Steve Cooley, and Jennifer Swearingen. I am particularly grateful to Dan O'Neil, my very thorough and competent editor.

I invite readers to visit the web site www.fireinthegrove.com for additional information and discussion about this book.

New York City, July 2005

Park Square, Downtown Boston. The first fire alarm-from Box 1514 in Boston's theater and nightclub district-was struck at precisely 10:15 P.M.

It was a car fire.

Within minutes of the alarm, Deputy Chief Louis C.Stickel arrived in his fire department car at the corner of Stuart and Carver Streets. As he pulled his bulky frame out of his vehicle, Stickel saw that his men had already extinguished the small fire in a car parked near the corner of Broadway and Stuart. Most of the apparatus had been dismissed and the "all-out" signal ordered. Only one engine and one ladder truck remained. Stickel decided that nothing here required the presence of departmental brass on this chilly night.

He was about to slip back into the warmth of his automobile when a fireman looking past him down Broadway said, "You got another one going up over there, Chief."

Stickel turned and saw a large black cloud of smoke pushing skyward several hundred feet down Broadway. He ran down the street toward the second fire, the remnants of the engine company screaming by him.

Stickel and his men knew exactly where they were going. "I saw it was the Cocoanut Grove," he reported later.

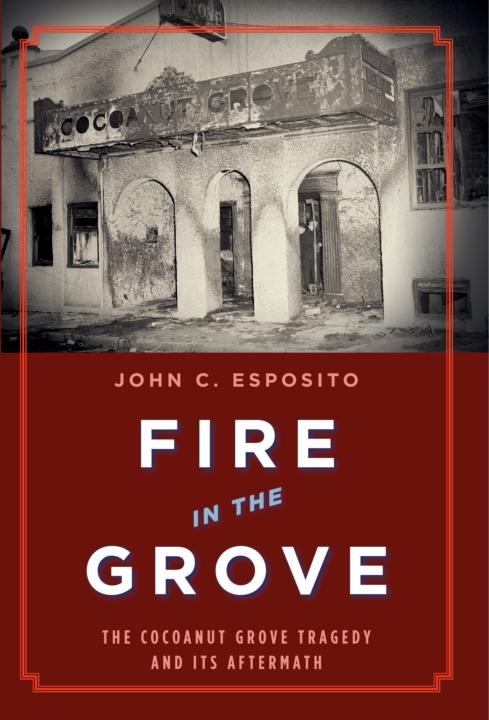

Boston's legendary nightclub was burning.

The first thing Stickel saw through the thick smoke was a man's head and arm poking through an impossibly small hole in the thick glass block that had weeks before replaced the store window of the Grove's New Broadway Lounge. The firemen began smashing at the glass block to help the man, but the awful rush of smoke and heat pushed them back. Stickel ordered his men to play the hoses on the man, but it was too late. He could only watch as the water splashed ineffectually off the block onto the sidewalk. "And then a flame took him up," Stickel said.

At the end of this long night, Deputy Chief Stickel would learn that the fire had started nearly a city block away from where he watched that first death, at the farthest end of the jumble of buildings that made up the Cocoanut Grove nightclub.

He would also learn that by the time he had arrived at the scene-at 10:23 P.M.-that nameless man reaching out through the glass block was one of nearly five hundred people-one of every two persons on the premises-who were either already dead or doomed. Stickel was witness to the worst nightclub fire in American history.

It had all begun just eight minutes earlier, at 10:15, precisely when that coincidental car fire alarm had been turned in.

Phillips House, Massachusetts General Hospital. It was a coincidence, as well, that at 10:15 P.M.Grove owner Barnett C.Welansky was far from the object of his pride, joy, and considerable fortune. Until recently, it would have been difficult to remember a night when this portly little martinet was not prowling around his club, hovering about his bartenders, waiters, and cashiers, fussing over every detail. But tonight, the forty-fiveyear-old lawyer-turned-nightclub operator lay in a private room at Massachusetts General Hospital, where he had been rushed twelve days earlier after collapsing with a heart attack. Since then, his condition had been complicated by pneumonia, and on this Saturday night, it must have seemed to him that his recovery would be very slow-if it was to come at all.